The story is a co-production. The writers are Ian Campbell and Joanna Ramos. Ian Campbell is the great grandson of Morag. Hopefully, the fact that this story is written by a man and woman together has resulted in giving the story a ‘multi-gender’ perspective. Ruth Joy has also edited the text.

The Birth of Morag MacKinnon on the Isle of Eigg

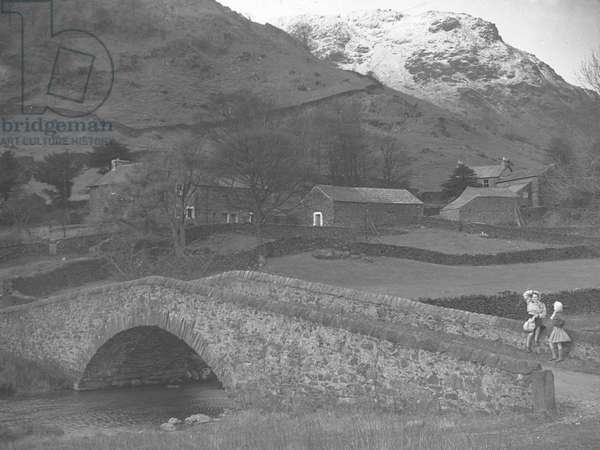

This story starts about 170 years ago – in 1855, when our main character, Morag MacKinnon was born. She was born on the Isle of Eigg,1 a small island off the west coast of Scotland.

Morag MacKinnon was born 28 May 1855 at Galmisdale in Eigg. It states on her birth certificate that she is ‘illegitimate’. In other words, her mother and father were not married.

Morag had many names. ‘Christina‘ was the name on the certificate, but ‘Sarah’ was written on the other documents. The islanders of Eigg spoke Scottish Gaelic, not English. However, the authorities were English-speaking, so they transcribed Gaelic names into their English equivalents on official documents. Sarah is the English equivalent of Morag.

Although she was illegitimate, her father admitted he was the father (as is evident from her birth certificate). His name was Ewen MacKinnon. We know little about Ewen, but it seems likely he was already married. Morag’s mother is Mary MacKay; she was 24 years old when she gave birth to Morag. Unmarried mothers were unable to look after their children, as they had to work; so, they often had to ‘give away’ their children. Mary and Morag were fortunate because Mary’s parents, Donald and Mary, were willing to look after Morag. In other words, Morag’s grandparents.

In nineteenth century Britain, unwanted children were often ‘got rid of’,2 so Morag was, in a sense, lucky to have grown up at all. During that time, the Church, the State and local communities shamed and chastised unwed mothers.

“True Story”

This is a ‘true’ story (semi-fictional), based on real persons and events. Morag MacKinnon is not a fictional person. She is my great-grandmother on my mother’s side of the family. Thus, the story is based on primary sources such as the various birth, marriage and death certificates, as well as the census reports available from ScotlandsPeople (National Records of Scotland).3 It is also based on other primary sources, such as the oral accounts of Morag’s descendants, for instance, her granddaughter, Rhoda Campbell Harkness (my mother), as well as others.

It is also partly and indirectly based on secondary sources, such as Camille Dressler’s Eigg – The Story of an Island (2007). The bibliography shows many other sources which I am indebted to, such as Hugh Miller’s The Cruise of the Betsey (1858/1988). As this is a semi-fictional account, I have also borrowed on other sources, such as Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye (1979).

I am also indebted to many other sources, some of which are listed in the bibliography; others were listed in footnotes and endnotes. However, my main ‘official’ sources are those, as mentioned, supplied by Scotlandspeople, that is, birth certificates, marriage certificates, death certificates, and censuses. In the end, the life of a human being is more than what is recorded in official documents.

Ironically, official documents have a better ‘memory’ than people. I’m fairly sure that most of the hundreds of the offspring of my great grandmother, Morag, do not even know of her name or her life! She has turned into a wisp of smoke like the Snow Maiden (Snihurońka) in the Ukrainian folk tale.

So this story is a scenario depiction of the real and imagined life of Morag. I have to admit that it’s not one of those ‘cosy’ stories people like to read. But it is based on assumptions that emerge from the records. In other words, it is inspired more by Thomas Hardy than by Charles Dickens.4

As mentioned, official documents and oral accounts are often incomplete. Thus, as a creative author, I will allow myself so-called artistic license, deviating from the ‘facts’ where it seems appropriate in order to ‘fill in the gaps’. The following story is ‘true’, but also semi-fictionalized by imagining a possible ‘scenario’. Thus, we will start with a brief historical background, followed by a semi-fictionalized account.

Brief Historical Background

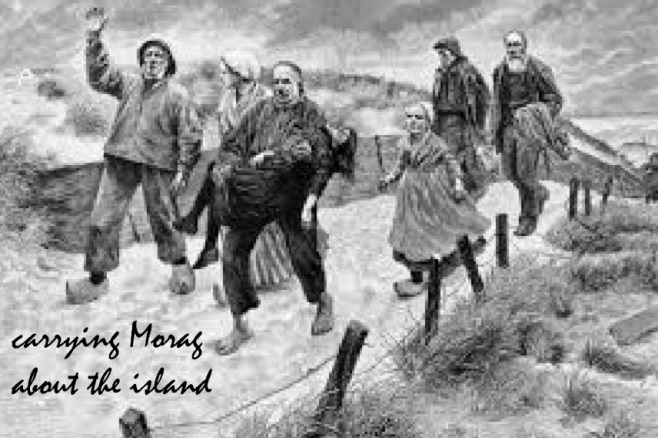

The reader is perhaps not a student of Scottish history, so he or she will have little or no knowledge of what life was like amongst the poor people in Scotland of 100-200 years ago. The poor people on the Isle of Eigg had no running water or sanitation; they had little or no medical care, and received little or no charity.5 It is a little unclear how much schooling children received.6 They had few rights. How well they lived would depend on their own hard work.

Morag’s grandfather, Donald McKay, was a crofter, and they had a small croft at Galmisdale in the south of the Isle of Eigg. A crofter is a type of tenant farmer. Donald didn’t own the land he worked on. The land was owned by the ‘lord’ or ‘laird’ (‘lord’ is called ‘laird’ in Scottish English).

Of course, the MacKays and MacKinnons spoke little English. They were ‘true’ Scots who spoke Scottish Gaelic. On the other hand, the lairds spoke English. The Gaelic-speaking peoples have been oppressed by the English-speaking rulers for hundreds of years.

In other words, the crofters were no more than ‘serfs’ – with few rights—and depended on the good will of the laird. If the laird wanted to evict all the tenants from his land, he was free to do so, and the government would back him up. The lairds were rich, and some had positions in the government or could wield political influence. The welfare of their tenants was something they rarely thought about. The laird was often more interested in the welfare of his livestock than the welfare of the people under his rule.

In 1826, some thirty years before the birth of our anti-heroine Morag, all four hundred inhabitants of the neighboring Isle of Rhum were evicted because the laird had found that he could make more money from sheep farming than arable farming.78 These people had lived on the Isle of Rhum for centuries; it was their ancestral home, but this was of little concern to the laird. Thus, with the blessing of the government, the tenant farmers were evicted. Many emigrated to Canada. But this is not the focus of our story here.

The point here is that the tenant farmers of Eigg never felt secure in their homes or livelihoods, as their welfare depended on the arbitrary decisions of the laird.

Our anti-heroine, Morag, the granddaughter of a poor crofter, was disadvantaged in many ways. Not only did she belong to the poor people with no rights, but she was also despised by the local community, the local church, and government officials, because she had committed the ‘sin’ of being born out of wedlock.

The crofters had to pay the laird for the tenancy of the croft. Of course, there was little money in circulation on the island – so payment would be made in kind like livestock, such as cows, sheep and hens; and crops, such as potatoes, oats, and barley.

The crofts were quite small—just a few acres of land. So when the crofter had ‘paid’ the laird for use of the croft and land there was little left to support his family. The crofter would have to depend on his own wits in order to feed his family — by fishing, hunting for birds and eggs, collecting wild plants and fruits, and so on.

Of course, finding eggs and plants was not the job of the head of the family; the children would also have to join in and help. As mentioned, there was little schooling for the children, so the children had to work as well. Parents often withheld their children from going to school for one reason or another.9

Obviously, crofters had to be vigorous and strong in order to survive. By the time Morag was six years old in 1861, her grandfather was already 54 years old. How much longer could he be strong of body in order to feed his family? In 1861, there were four people living in the McKay croft: the grandparents, Donald and Mary; their daughter, Christy; and their granddaughter Morag who was six years old.10

The Campbells

There were several crofts in the township of Galmisdale. By the time Morag was a young girl, the Campbells had moved into one of the neighbouring crofts. There were six people living in the Campbells’ croft: the parents, Donald and Margaret; and the sons and daughters, Ann, Ruaridh, Angus, and Margaret. This piece of information is important to our story, because the paths of our anti-heroine, Morag, and our ‘antagonist’, Ruaridh Campbell, would cross one fateful day.

The people living in the township of Galmisdale would obviously all get to know each other. Not only that, but they were often dependent on each other’s help.

The MacKays

As mentioned, the MacKays were only four people living in one croft cottage. But it was more typical that the families living in the crofts were quite large — ten or more people living in one croft, with one, two, or three rooms. So they would be living together in a small space. In the winters it was cold and dark; they would stay inside to keep warm.

There were few trees on this northern, windswept island, so there was not much wood to burn in their fireplaces. The islanders had to cut peat in the summer, which had to be dried. It was then used as fuel which they burned in the winter to keep warm.

The MacQuarries

The families living at Galmisdale were ‘lucky’ in that their cottages had two or three rooms with windows. Some of the poorest people on the island lived in so-called ‘black’ houses with no windows and an earthen floor.11

The MacQuarries were very poor, they lived in such ‘black’ houses, and other people on the island tried to avoid them.12 The black houses had a hole in the roof to let out the smoke from the fire. The only light inside the cottage came from the doorway. The floors were just cold, damp earth.

As mentioned, there was no doctor on the island. If people became sick, they just lay in their beds hoping to get better; they often died from untreated illnesses. There was no provision for old and sick people, so they would often just wither away until they died of sickness and starvation.13

As noted above, the children also had to work to provide the family with food. Young boys of five or six years old had to climb the cliff rock faces to find bird’s eggs and young birds, and the young girls had to gather wild plants and fruits, and shellfish and seaweed on the beaches. They would also have the job of fetching the water from the well, and so on.

Sources

- The sketch here shows the An Sgurr of Eigg as drawn by the botanist Michael Pakenham Edgeworth. For more detailed information refer to my book, The Isle of Eigg and The Story of Some of its People (2022). ↩︎

- ‘Baby farming’ is the historical practice of accepting custody of an infant or child in exchange for payment in late-Victorian Britain. Dorothy L. Haller explains in her article “Bastardy and Baby Farming in Victorian England” (1989-90) how so-called baby farmers on the pretence of looking after an unwanted child would actually starve the child to death, feed it with poison or smother the child in their care, and dump the body in the river or on the street wrapped in rags or newspaper; or, as reported in this story, throw them in the sea. ↩︎

- https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/ ↩︎

- Both writers depicted social reality, but Thomas Hardy was an exponent of British Naturalism, applying scientific determinism to the novel, where he viewed man (and woman) as a victim of fate and social laws. Dickens on the other hand has been criticised for being a sentimentalist in his exaggeration of pathos, which they said was overdone and inauthentic. ↩︎

- Refer to Miller, H., The Cruise of the Betsey, Edinburgh. 1858. ↩︎

- I am a little unsure when the first school was established on the Isle of Eigg. But compulsory primary education was introduced in Scotland in 1872. However, Dressler (2007) notes that a parochial schoolmaster was appointed in 1792. The ‘school’ was extended in 1829 “paid for by Dr MacPherson”. (pages 69-70). In other words, there was some schooling, but it was not thoroughly introduced. ↩︎

- Refer to ‘The History of the Highland Clearances – the Hebrides – the Island of Rum’ https://electricscotland.com/history/clearances/32.htm Read: 20 March 2022. ↩︎

- ‘The History of the Highland Clearances’ – the Hebrides – the Island of Rum: This island, at one time, had a large population, all of whom were weeded out in the usual way. The Rev. Donald Maclean, Minister of the Parish of Small Isles, informs us in The New Statistical Account, that “in 1826 all the inhabitants of the Island of Rum, amounting at least to 400 souls, found it necessary to leave their native land, and to seek for new abodes in the distant winds of our colonies in America. Of all the old residents, only one family remained upon the Island. The old and the young, the feeble and the strong, were all united in this general emigration—the former to find tombs in a foreign land—the latter to encounter toils, privations, and dangers, to become familiar with customs, and to acquire that to which they had been entire strangers. A similar emigration took place in 1828, from the Island of Muck, so that the parish has now become much depopulated.” https://electricscotland.com/history/clearances/32.htm Read: 20 March 2022. ↩︎

- Dressler (2007), p. 70. ↩︎

- See the census on Scotlandspeople. ↩︎

- Refer to Dressler (2007). ↩︎

- Conversation with my mother. ↩︎

- Miller, H., The Cruise of the Betsey. Edinburgh. (1858). NMS Publishing. 1988. See pages 216-219. ↩︎