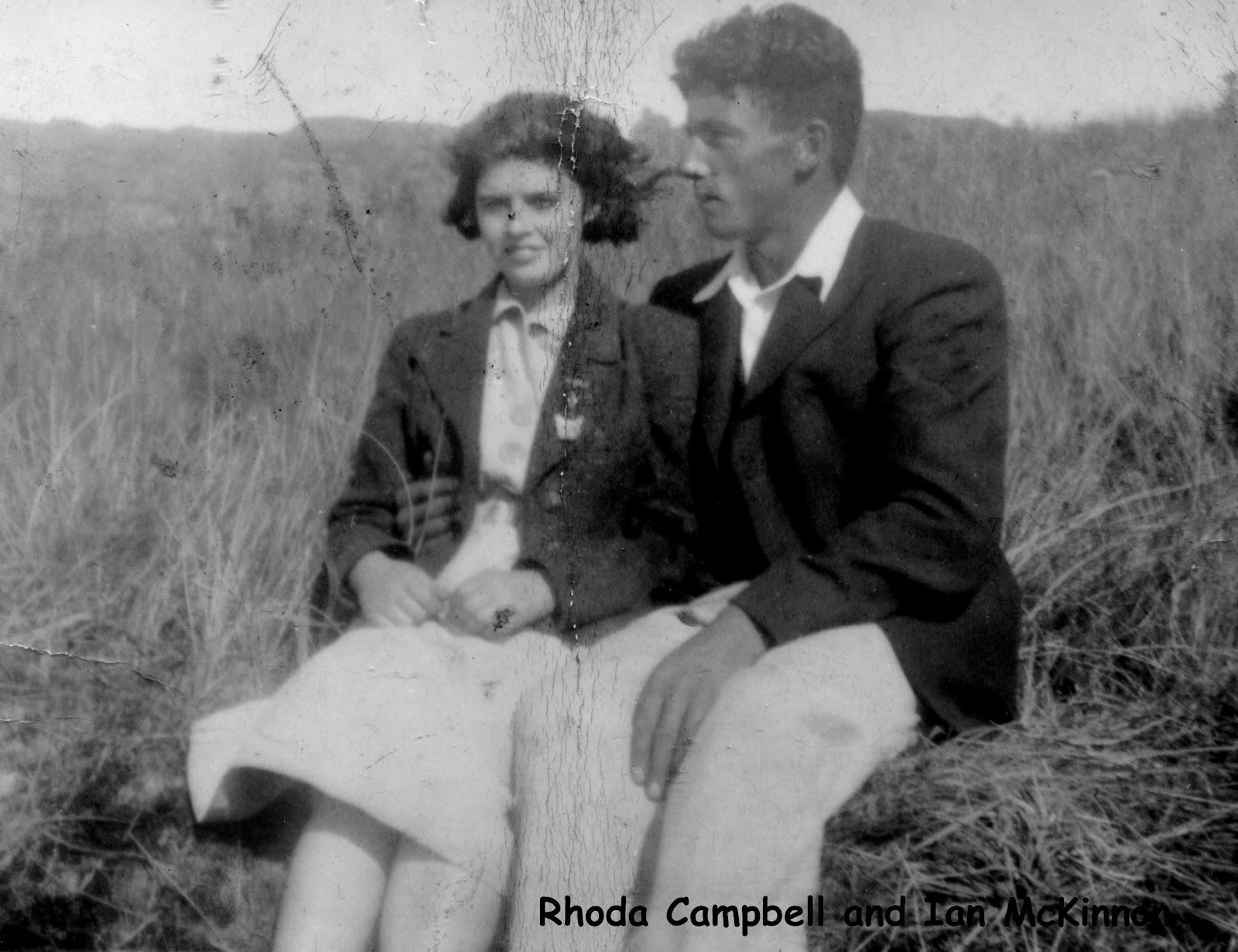

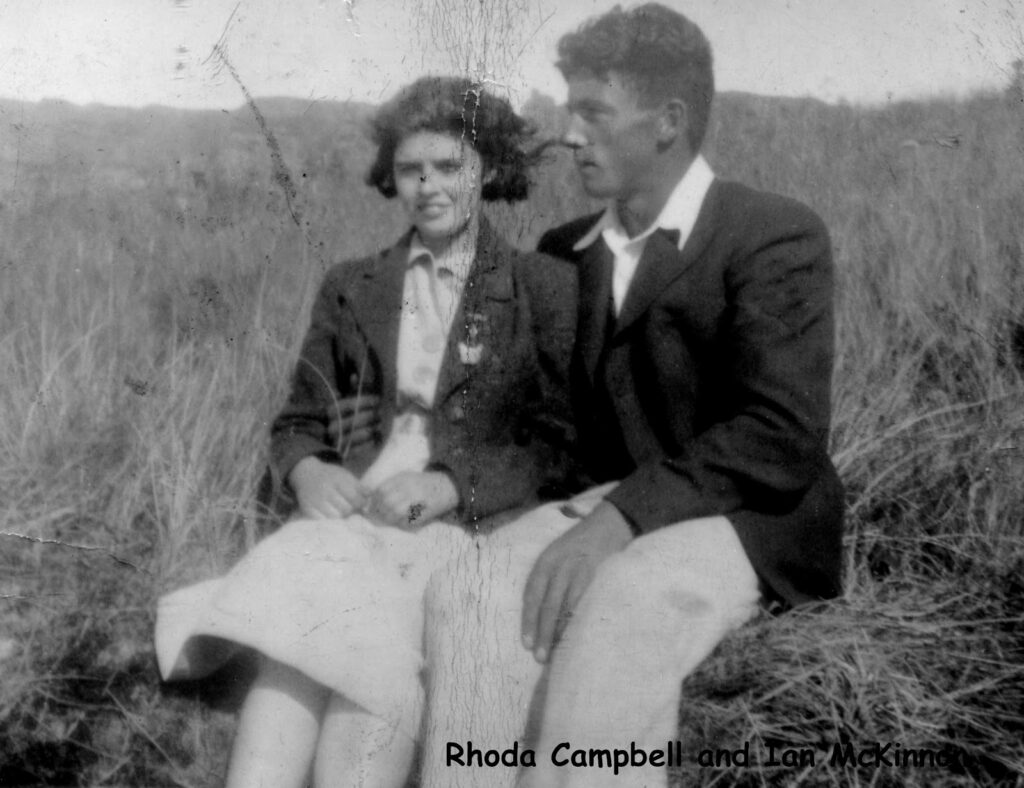

This post describe the MacKinnon boys, Ian and Dugald, with a bonus story of how they both dated my mother.

Dugald MacKinnon

Dugald was born in 1912 at Cleadale. His father was John MacKinnon (of Bayview), and his mother Kate MacDonald. His father died in 1938 at Bayview. John MacKinnon’s father was Charles MacKinnon (smallholder), his mother, Mary (m.s. MacLellan).

When his father died, Dugald, after his years of ‘tramping in the West’ came home to look after his widowed mother. He got a job at Sandavore farm.

“I had to look after the geese, fatten them up for Christmas. You see, well … I was young and not very patient. So when the time came to kill them and they still didn’t look fat enough, I just filled them up with water to make them look really plump and that did the trick; the cook never knew any better” (Dressler, 2007: 125).

According to Dressler (2007: 102), Dugald’s uncle was Tearlach MacKinnon.

“He had struck it rich in the Klondyke Gold Rush. He sent enough money home for an entirely new house to be built in 1896. The old house was turned into a byre. Bayview, the most modern house in Cleadale, was the first crofthouse to take in visitors.

‘My uncle did very well in Canada afterwards. I believe there is still a block of flats named after him in Vancouver!’ tells Dugald MacKinnon, who remembers seeing his uncle once in his childhood. ‘He was wearing a fur-coat , right down to his ankles, we’d never seen anything like it!’

My mother dates the McKinnon boys, Ian and Dugald

The photo above shows my mother, Rhoda Harkness, nee MacGillivray, together with Ian McKinnon; the photo was most probably taken on Eigg before the Second World War, perhaps in 1940. My mother doesn’t seem to mind having the arm of this handsome man round her waist, but she isn’t encouraging him too much either.

Ian MacKinnon, Dugald’s younger brother (son of John MacKinnon and Katie MacDonald), courted my mother and was very handsome. She said he ended up in Reading working for the police. I wonder if he might have been the one that ‘got away’. Perhaps my mother still had a longing for him after she married my father. Why else did I end up with the name ‘Ian’. No one else in the generations of the families of my mother and father were called ‘Ian’. Of course, this is not necessarily logical as my brothers Alistair and Stuart did not have forbearers name-wise on the family tree either.

My mother was no doubt popular with the boys of Eigg in the late 1930s, and in 1940, the year she got married. According to my mother she said “I only weighed seven and a half stone but had the bulges in the right places and was quite good looking.”

My mother talks about Dugald and Ian

“Dugald MacKinnon was my boyfriend. Ian MacKinnon was much better looking though. Ian took me to the dance on Eigg and you’ll never guess what he gave a quart of boiled sweets. He became a policeman in Reading. He had a hair lip, though not a bad one.

John MacKinnon came from the Isle of Muck. Duncan Ferguson invited me for tea and scones (Duncan Ferguson’s father); he did fancy me when I was in my teens; but as I was saying, he was a staunch Catholic and I was a Protestant; and that was important in those days” (Conversation with my mother, August 4th, 2007, 6 Fitzjohn Close).

”Oh! I really loved him (Ian) at that point. But we kind if drifted away from each other. But then I met your dad …..” (Conversation, October 31st, 2007).

My mother was certainly a ‘looker’. Weighing in at 7 and half stone, but with all the ‘bulges in the right places’, a shock of black hair – intelligent and smart, and a family heritage on the island. But she was also ‘modern’, having grown up in the city of Glasgow – an English speaker. Thus, it was no surprise that the Gaelic-speaking men of the island were competing for her affections.

She mentions Ian MacKinnon, Duncan Ferguson and Dugald MacKinnon. But undoubtedly there were many more! According to my mother, Ian MacKinnon was more handsome than his older brother Dugald (Dugald was born in 1912, Ian in 1914). Admittedly, I would have loved to have had Dugald as my ‘father’, as he was a strong and resourceful individual!

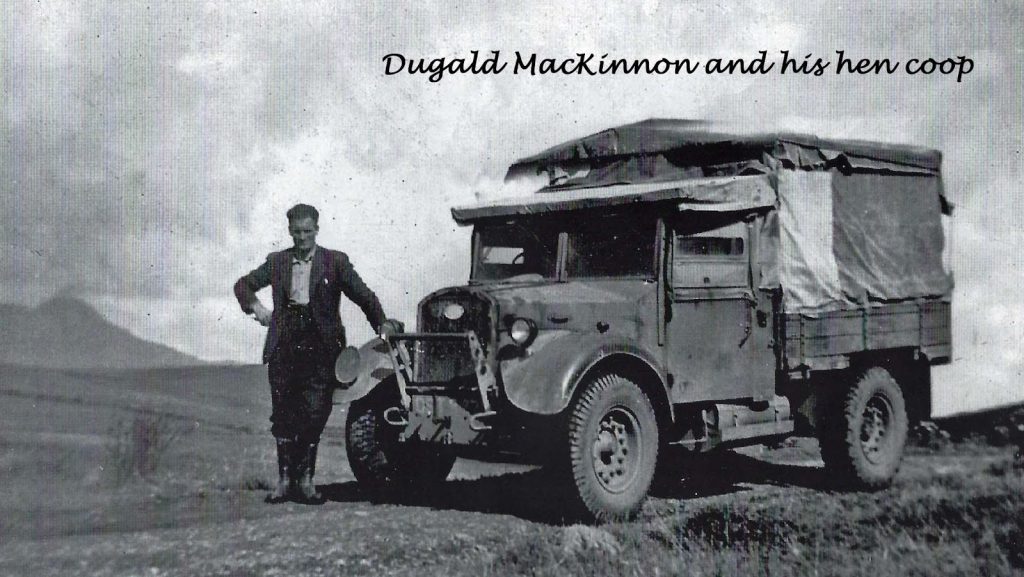

Dugald McKinnon – Bus Driver, Ferryman

Dugald was also the Eigg ‘schoolbus’ driver in the late 1940s, using an ex-army lorry (Eigg Photo Archive, K. & D. MacKinnon 50). This was a Fordson V8 which was “fairly temperamental and did not like cold mornings, and Dugald used to coax it to life by warming the engine up with a paraffin heater under it at the front. The big problem was after the war was petrol which was still rationed. Always resourceful, he would use paraffin once the engine had warmed up and it would go quite well” (Dressler, 2007: 139).

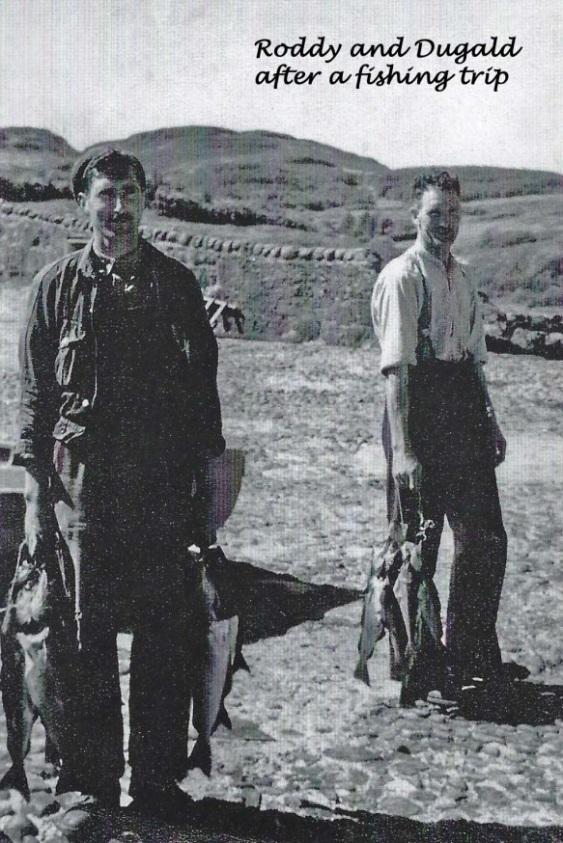

Dugald was also a ferryman when he got married in 1944. It seems the Campbells and MacKinnons monopolized the ferryman job on Eigg; Roderick Campbell and his son Donald were both ferrymen, and I think Donald’s son Roddy was also the Eigg ferryman.

‘Whisky Galore’ – Dugald’s ‘Story’

The ‘fishing’ photo above shows Roddy Campbell and Dugald MacKinnon (married to his ‘cousin’ Katie MacKinnon), perhaps taken during the period of rationing (Eigg Photo Archive, M. & C. Campbell 8).

On reading Camille Dressler’s book, Eigg – the Story of an Island (2007), she describes many colourful and resourceful Eigg characters, such as Katie MacKinnon. Her husband Dugald also seems to emerge from the book as a resourceful character. She explains that in the post-war period a croft hardly provided enough to support a family – and that crofters had to depend on their wits. She reports that Dugald was the first islander to own a motor car and also a tractor. The car was used as a van to transport goods.

In 1944, towards the end of the war, some of the island’s men found a 40 gallon drum washed up on the sand near the pier. At first, they approached it with caution, as they feared it might be some kind of explosive. Dugald finally plucked up the courage and pierced it open, and to their great surprise they found that it contained pure spirit!

After some experimentation by Dugald’s mother they discovered it was drinkable if they diluted it down 2 ½ times and added some treacle. Apart from drinking it, it was also used in Tilley lamps. The 40 gallons were distributed equally between the island’s households. This was during times of dearth and rationing during the war! (Dressler, 2007: 134-5).

Of course, this was also a way of bypassing strict rationing laws, and if they had bought the drum of spirit, or received it by some other means, this would constitute breaking the law with the risk of several years’ imprisonment. Dividing the spirit between all the islanders was perhaps also a way of avoiding any possible investigation – one could hardly arrest everyone on the island!

One might even say that the islanders were perhaps fortunate during the Second World War, as Eigg had traditionally had a self-supporting economy: the land, sea, and hard work provided what they needed. So there may have been strict rationing laws during the war, but this surely didn’t cover food obtained by one’s own efforts, such as fishing.

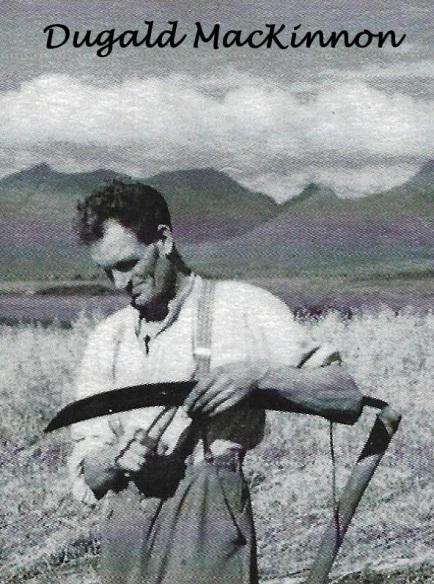

The Corn Harvest

The corn harvest started in September, which was generally a dry sunny month, with a full moon around Michaelmas. Thi enabled the islanders to work late at night to finish the harvest.

‘I have seen Katie and me up until two in the morning to finish cutting the corn,’ recalls Dugald. ‘You had to, in case the weather changed. The whole field could be flattened and that was your harvest ruined.’

Horse-drawn reapers were used to cut the sheaves with one or two people behind to make the sheaves into stooks, three or five together. Then, when the stooks were dry enough, the corn was taken in and the corn stack carefully built, sheaf by sheaf.

‘You’d be careful to put the sheaf at an angle so that the rain would run on the outside and not go in the stack,’ explains Katie. ‘When the stack was built, you could just take a handful of corn at a time to feed the horses or the hens. You had to winnow it first before you’d give it to the hens.’

Dugald could picture it still: ‘I mind Angus and his father going to the top of the quarry in Cleadale to winnow their corn, there was always a good breeze there.’ (…)

‘In my mother’s time they would have taken the corn to the mill at Kildonnan and they would have their own oatmeal,’ recalls Katie.

This is a good description of how the economy of the island would be transformed in the following 50-70 years. Obviously, this manual farm labour was not sustainable in the long run, with the introduction of new machinery, and the competition of cheaply produced agricultural products. In other words, the decimation of culture was caused by economic change, which is a basic Marxist principle. Thus, the destruction of the old methods of production, also partly resulted in the destruction of Highland culture, the loss of the Gaelic language, and so on.

‘Killing the otter’ – Dugald the story-teller and preserver of culture

Dugald was certainly a great story-teller! I have ‘stolen’ his stories from Camille Dressler’s book, “Eigg” (2007). One of his fascinating stories is Marbhadh am Biasd Dubh (‘Killing the Otter’), which was performed during the island’s ceilidhs (a social event with Gaelic folk music and singing, traditional dancing, and storytelling).

Dugald is reportedly the last Eiggach to perform the dance. “

‘It was more acting than dancing, originating in a forgotten past. (…) It mostly involved looking for the otter behind or even between the women’s legs. You made a laugh of it and you came in with the otter on your back and it was supposed to be alive and escape and disappear again and again.’ explained Dugald” (Dressler, 2007: 151).

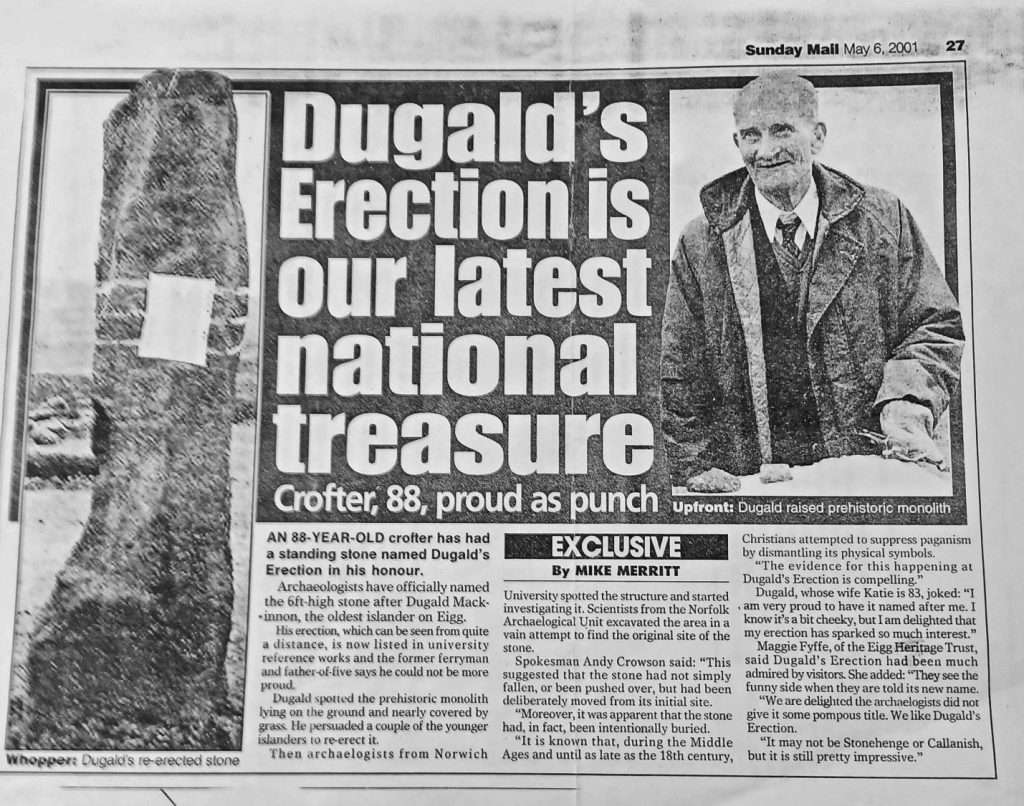

Dugald’s Erection

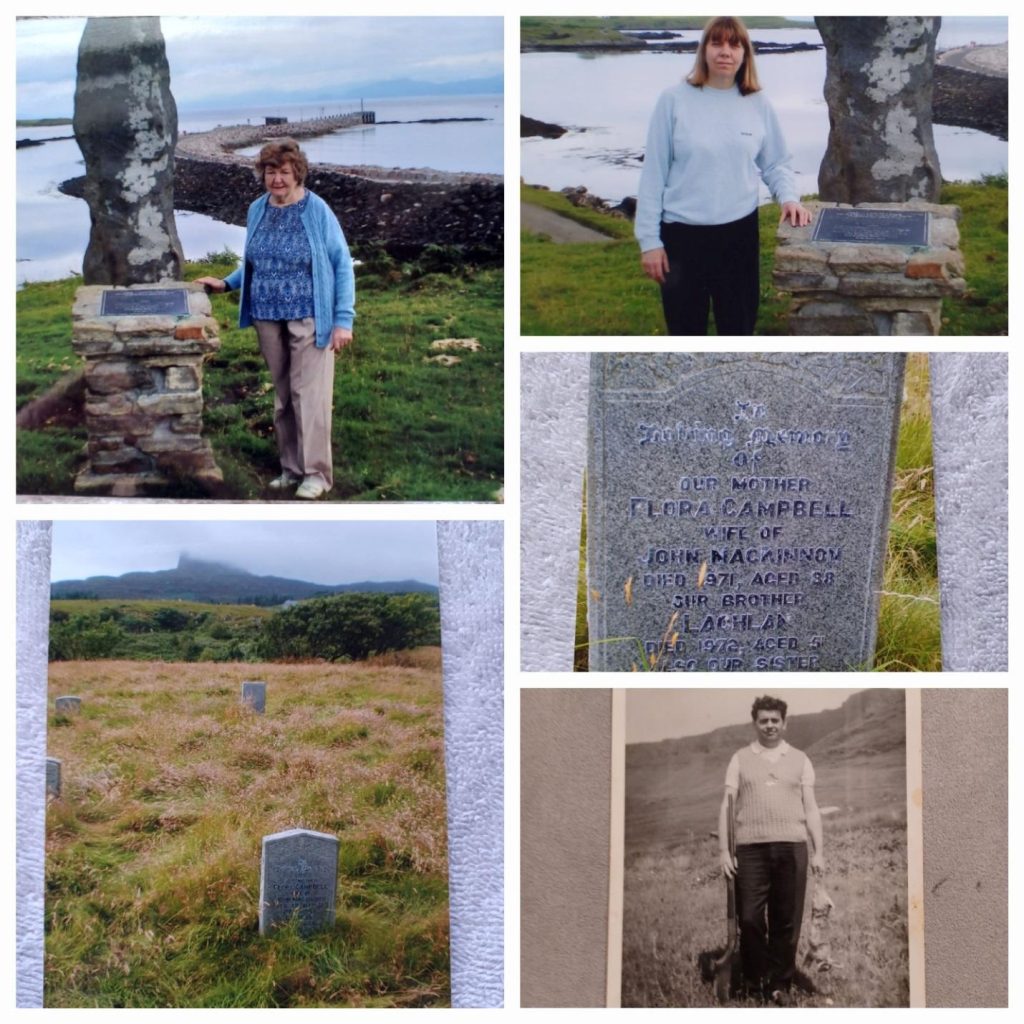

I never managed to see “Dugald’s erection” when I visited Eigg in 2007, but my cousin Dawn Driscoll became intimate with it. Dawn and was able to send me a photo and newspaper article. I will first insert the erection here, or rather an article about his “erection”.

Calling the standing stone an ‘erection’ was perhaps not so stupid. As mentioned elsewhere here, ‘Sheela na Gig’ was a manifestation of female fecundity. In other words, many historical artefacts can be understood in terms of fecundity. For example, Stonehenge can be viewed as a fertility monument with stones positioned to cast phallic shadows, as part of a fertility cult. Thus, “Dugald’s erection” may have been part of a local fertility cult on Eigg.

Comically, Dugald’s stone is 6 foot high. Men like to boast of 6 inches, more ambitious men boast of nine inches. In other words, the stone was a x12 model of a human erection.

Dugald looks very proud about his ‘erection’ in the newspaper article of 2001. I have also suggested elsewhere here that the ‘mountain’ of Eigg, the An Sgurr, has phallic associations; An Sgurr is composed of volcanic rock. Obviously, volcanoes have phallic and ejaculation associations.

Dawn, Bett, and Dugald’s Erection

The photos show Dawn and her mother Bett next to “Dugald’s Erection”.

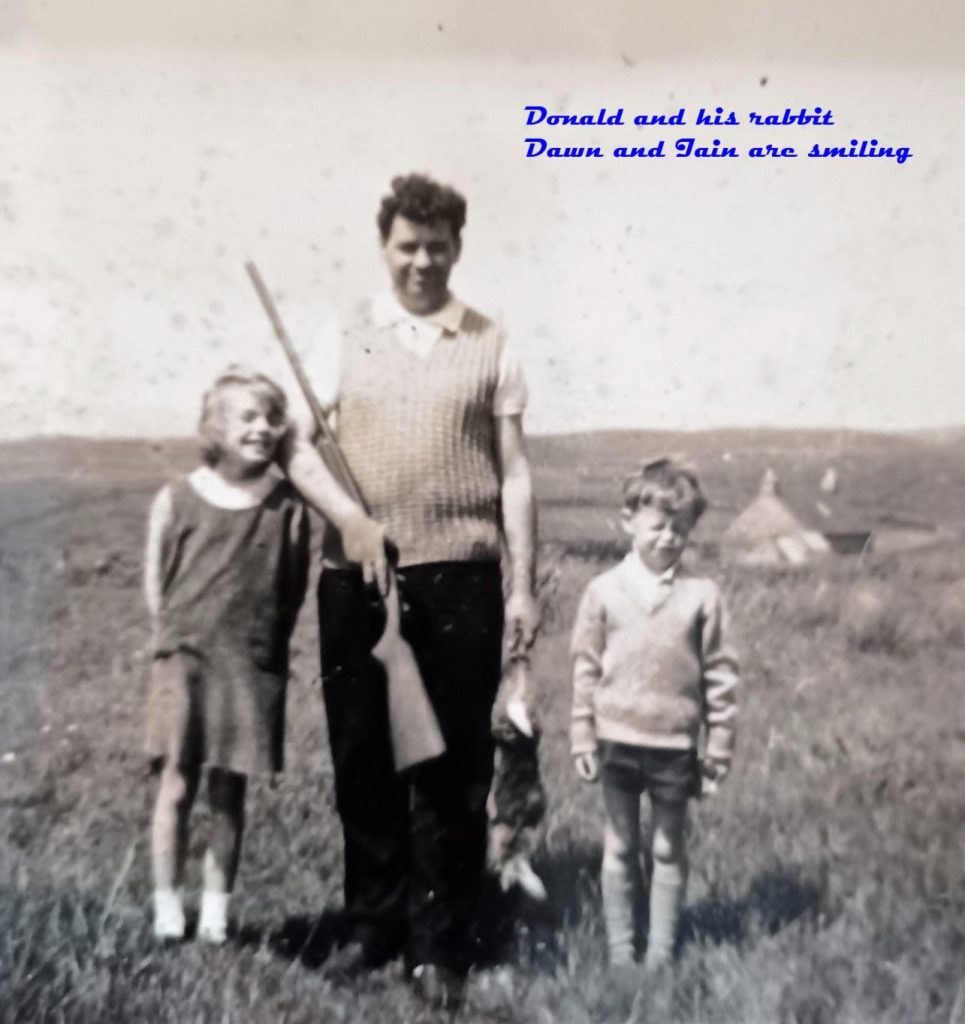

‘Poaching’ rabbits

The photos also show Dawn’s father with a rabbit he has hunted.

Rabbits proliferated to such an extent that every year, the estate had to employ two trappers from the mainland to help the four crofters employed from October to March in order to keep numbers down (…). Like shepherds on their hirsels, each trapper worked on his own patch, using snares as well as gin-traps. Trapping went on well into the 1930s, and in his first winter Dugald McKinnon remembers how he managed to catch as many as 2000 pairs (…) at sixpence a pair! The rabbits were hung on wire lines, so many lines for each trapper. (…) The rabbits were then sent to Glasgow in great wicker hampers at a profit of one shilling per pair.

In other words, it is highly likely that Dugald provided Donald with the rifle to shoot the rabbits, though this picture was taken many years after the event described above. Although the Eigg islanders probably enjoyed rabbit meat, Donald was unable to convince his children that this ‘bunny’ food was wholesome, as they had most probably been brought up to believe that rabbits were friendly and loveable animals, as recounted in the numerous stories for children.