Morag is Lying on her Deathbed1

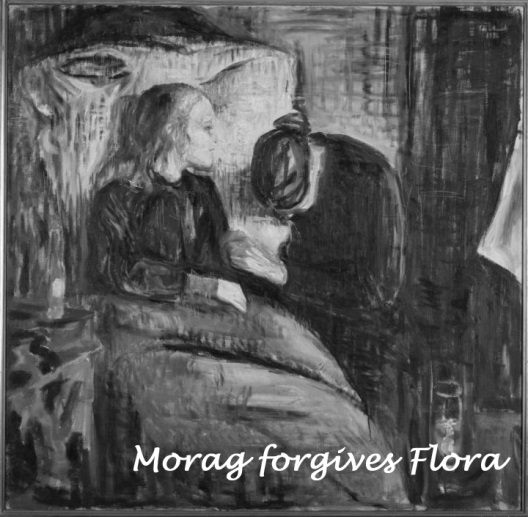

After the birth of her tenth child, John, Morag’s sickness took a dire turn, so it became evident she did not have long left in this world. Lying on her deathbed, Morag felt she did not want to meet her death with hate in her heart. She had already forgiven her husband for his sins in her own mind. But she still bore a grudge against her sister-in-law, Flora; she had always lashed her with the tawse on numerous occasions and said wicked things to her.

Flora also started to feel guilty after she realised Morag was a very sick woman. Flora had repented of her treatment of her brother’s wife. She realised it was a sin that she had chastised Morag so hard. Flora visited Morag one day when she lay on her deathbed and asked for forgiveness. At first, Morag had been unwilling to forgive her for her abuses. But not wanting to go to her grave with hate in her heart, she forgave her sister-in-law. They held hands for the first time while she lay on her deathbed.

The Death of Morag Campbell March 26th, 1895 and her Burial

The many years of repeated childbirths, deaths of her children, working hard in the fields between pregnancies, the whippings by her sister-in-law Flora, the violations of her whisky-headed husband, and an inherited sickness, finally took their toll at the age of thirty-nine after giving birth to ten children.2 She died on March 26th, 1895, just two months after the birth of her youngest child John (b. 15th Jan 1895, d. 1897). It was stated on her death certificate: “cause of death: after eight years of paralysis.”

In other words, during her eight years of “paralysis”, she had given birth to several children. Her death and the cause of her death were not certified by a doctor. The fact was, as mentioned, people on the island received no medical help from the government. Morag died two years before the Isle of Eigg received its first medical officer in 1897.3

Preparing the Burial of Morag

Ruaridh had buried his son Hugh five years before. Minister Sinclair proposed that he place the hilt of the Viking sword that had killed and beheaded Saint Donnan in Hugh’s grave. In other words, this was the sword that had beheaded Donnan and his monks several centuries before.

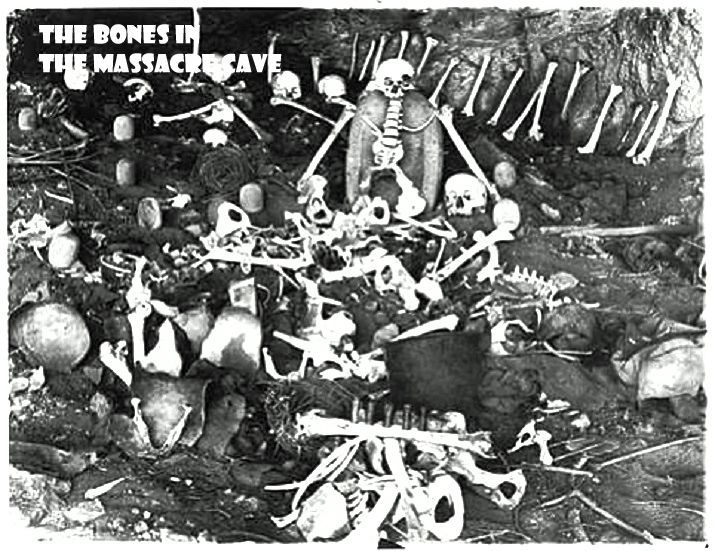

The Isle of Eigg had throughout the centuries been the scene of many such slaughters. One such slaughter was the ‘Massacre of the Uamh Fhraing’ (the Cave of St. Francis. In the sixteenth century, the MacLeods murdered every single inhabitant on the Isle of Eigg, except for Morag’s ancestor, Flora MacKinnon; she was the old woman of Hulin, who had stood up to the MacLeods. The Cave Massacre had been revenge for the slaughter of the MacLeods on Castle Island who had ‘molested’ the women of Eigg.4

The ‘Massacre of the Uamh Fhraing’ had occurred more than three hundred years before. Nearly 400 islanders were smoked and choked to death; and yet the cave was still full of the skeletons and bones of the inhabitants.

The newspaper The Scotsman published an article by James Wilson5 describing the natives of Eigg as cannibals.6 He writes,

“The bones of the victims lay scattered about the floor in various places, a considerable number at the far narrow end, to which it may be supposed the wretched creatures had retreated when the horrid choaking smoke began to roll its fatal wreaths upon them.

That they are a high-minded and romantic race these islanders and extremely tenacious of their ancestral glories is evident from this; that during the potato harvest, the pigs are put out of the way of doing mischief by being all cooped up in this same ancestral cave; and fine mumbling work they will make of it, while grumphing to each other ‘de mortuis nil nisi bonum’.

Now as the people eat the pigs, and the pigs the people’s predecessors, it follows logically that the present natives are a race of cannibals of the very worst description.”

This article had been brought to the attention of the minister John Sinclair, who discussed the matter further with the Laird, Robert Thomson. The matter was further discussed with the island’s registrar, James Campbell, an important man on the island.

It had also come to their attention that, apart from the fact the bones were providing the island’s pigs with nourishment, they had also become macabre ‘curios,’ in that tourists and others visited the cave, taking skulls from there to show their friends ‘back home.’ The author, Sir Walter Scott, started this macabre tradition when he visited the island in 1814, taking a skull from the cave, which he later exhibited in his home, Abbotsford Manor.7 The scientist Hugh Miller also followed in Scott’s footsteps, taking a macabre interest in the cave.8

Minister Sinclair felt that the newspapers and the tourists, not to mention the pigs, showed no Christian respect for the historic genocide of the people of Eigg. He proposed to Laird Thompson that they should give the bones in the cave a Christian burial, to which Thompson agreed.

They all agreed, but were unsure who should collect the bones and dig the grave. Minister Sinclair proposed that they talk to the ferryman, Ruaridh Campbell. This was while his wife, Morag, was lying sick on her deathbed. Ruaridh had a strong back, and with the help of others, he could collect the bones and dig the grave. Ruaridh only spoke Gaelic, so the Laird’s factor, MacDonald of Tormore, should ask Ruaridh if he could do the task, as MacDonald spoke both English and Gaelic.

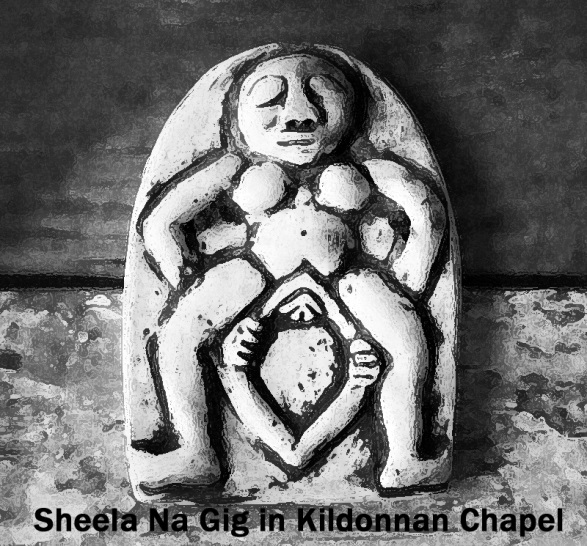

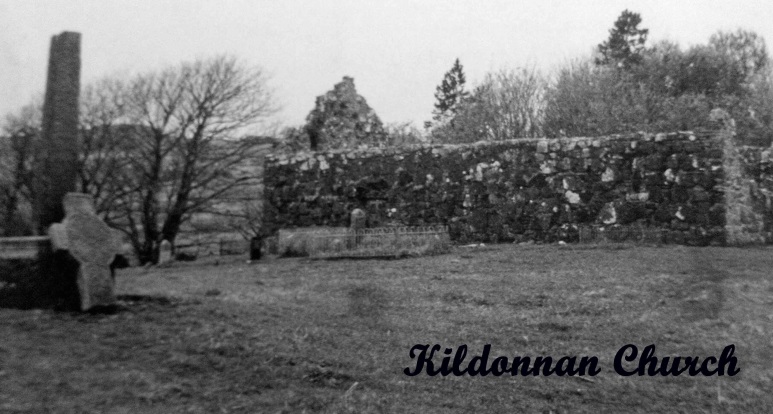

MacDonald talked to Ruaridh the following day, and Ruaridh agreed on the condition that the minister agreed to his wife being buried in the roofless Kildonnan Kirk, beneath the stone effigy of the pagan Celtic goddess of fertility, Sheela na Gig.

The minister opposed the idea of Christian churches being adorned with ‘pagan’ images, but had agreed, because the goddess, although a goddess of fertility, was also a goddess that warned of lust. It was common knowledge on the island that Ruaridh had been tempted throughout his life by the ‘demons’ of lust and drink. At least, he had only two ‘mistresses’ in his life, Uisge Beath and his wife Morag. Minister Sinclair had said to MacDonald when asked about Morag being buried in the kirk beneath the effigy of Sheela na Gig,

“Satan, the prince of this world, fans the flames of lust in the hearts of men and women.9

“The Bible says ‘Be fruitful and multiply,’10 but Ruaridh’s progeny are not the result of his following the words of God, but rather due to the demon of Lust and Drink, which fill our island with s’nfulness and rags.11 The men of this island are clever at catching rabbits and love the meat of the small animal.12

Perhaps this has poisoned their bodies and minds, so they behave like rabbits. Good Christians do not need to breed like rabbits, but should be more responsible instead.13 So it is well and fitting that she be buried under this pagan goddess, as Morag was certainly fertile, giving birth to ten children, and her husband is certainly lustful.”

Ruaridh and his friends dug Morag’s grave on the morning of the burial. The other grave for the bones and skulls of the ‘Cave Massacre’ had been dug some time before.

The burial was to be in the afternoon. A short service was also to be held in the roofless Kildonnan Kirk, where Morag and the victims of the Cave Massacre were to be buried. The news had quickly spread around the small island that the victims of the Cave Massacre would finally have a Christian burial due to the efforts of Laird Thompson and Minister Sinclair. Despite his illegal gun-running activities, Laird Thompson was a religious man.

The medieval Kildonnan Kirk is quite small in dimensions, so it couldn’t accommodate the hundreds who wanted to attend the burials and services. Only a few would be allowed to be present at the ceremony within the walls of the old kirk—the important people of the island, such as Laird Thompson, James Campbell, the registrar, and the close family of Ruaridh.

The other islanders congregated at the Kildonnan graveyard adjacent to the kirk.

While Morag was lying on her deathbed, she would sometimes say to her husband, Ruaridh, “Ah dae wantae die. A’m still young. Wha wull look efter ye ‘n’ a’ mah bairn whin I’m not here tae tak’ care o’ ye a’?”1415

Trying to comfort her he would say:

“Dae nae worry aboot us. Yer are not going to die. Yer still young ‘n’ bonny. Ye wull be forever young. Yer juist aff tae anither steid, called Tír na nóg, th’ ‘land o’ th’ young’ – th’ realm o’ everlasting youth, beauty, abundance ‘n’ joy. Ye wull na mair be paralysed whin ye come thare fur it’s an’ a steid o’ healing ‘n’ health. ‘N’ ye wull meet yer bairns thare, fur thay hae passed tae th’ ither side. Ye wull meet Morag, Anne, Hugh ‘n’ Mary.”16

Tears came into Morag’s eyes as she lay on her deathbed holding her husband’s hand.

“Bit mind tae bury me beneath Sheela na gig in th’ kirk – she wull protect me ‘n’ mak’ sure that ah kin cross tae th’ ither side. ‘N’ mind tae ask mah elder sister Christy tae sing Tír na nÓg at mah burial,” Morag said to her husband, Ruaridh.

Morag hugged her husband. She asked, “Ruaridh – whaur is Tír na nÓg, th’ land-of-the-ever-young; whaur a’m aff tae?”

“It lies somewhere tae th’ west, whaur th’ sun sets. Whin ye die in this world, yer soul wull sail tae th’ shore o’ th’ Great Sea, ‘n’ from thare ye wull be ferried o’er th’ waves tae th’ Isle o’ Tír na nÓg. Ye wull nae need win` nor sail nor rudder. Ye wull speed lik’ a bird ower th’ sea; ‘n’ th’ wish o’ th’ Fate wull guide ye.”17

Before Ruaridh left her, she sang Tír na nÓg, just like she had done on their first encounter.

Tír na nÓg18

The roar of the waves, plaintive their sound,

As they chant in my ear thy praise,

The song of the bens, the fountain and stream,

With thy music downward flow;

By day my witchment ever thou art,

Thy longing eternal me wounds,

And by night thou art ever my dream,

Tir nan Og.

Death nor sorrow in thy Beauty-land lives,

In the grave are deceit and guile,

The brave ever drink of thy generous life,

Gladness swims in the clouds;

Lofty stars by day and by night

Shine softly through a mist,

Mellowest harps grow up in thy woods,

Tir nan Og.

Behind the waves, the ship of my dream

Goes sailing as of yore,

The wish of Fate ever speeds her way

Silent and swift as a bird;

White Barge, leave me not in distress

On the shore of mighty seas,

Depths of pain and love me song-draw

To Tir-nan-Og.

Ruaridh and Morag were both Christians, but like many of the other islanders, they also believed in the old Celtic traditions — they believed in the ‘other-worlds’, the invisible realms of gods and spirits, fairies, elves, sparkling heavens as well as brooding hells.

Morag had asked Ruaridh as a last request on this earth, if he could say a blessing at her burial in the name of the Celtic goddess Arduinna, the protector of women. Arduinna was the protector of violated women. Children born out of wedlock, and women abused by men, were the first to be admitted to the Celtic heaven, Tír na nÓg.

If there is such a thing as reincarnation, abused women would be reborn and persecute violators; they would emerge as spirits after their deaths to torment the tormenters of women and children. In their spiritual form, they would appear before the tormentors of women and children, ‘look them in the eye’ and burn themselves into their memories as long as they lived. The spirit would live inside them, so they would have to wear her like a scar.19

Thus, after Morag’s death and burial, she lived on as a spirit and haunted the burn where she and Ruaridh had first met — near the bridge over the burn at the bottom of Kildonnan Hill.20 Her spirit would emerge from the burn in the form of a beautiful young girl.

As the drunken men were making their way home from the local tavern with thoughts of abusing their wives and children, she would read their minds and entice them to join her in the burn; she would drown them when they were engaged in lustful intercourse. Thus, there were many unexplained drownings on the island. But the women and girls of the island flourished, when not subjected to the violations of husbands and fathers.

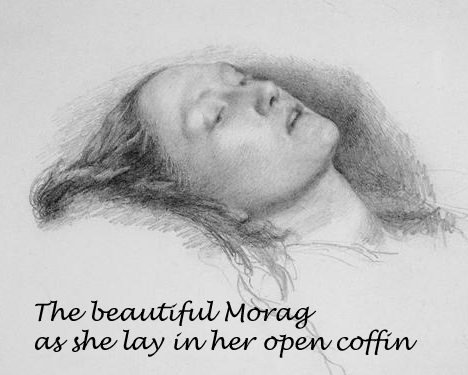

Morag’s wake21

Morag had made her husband promise not to fight all the young lads of the island as he had done at his father’s wake. One of the lads, armed with a stout stick, had maimed one of the other lads.

But then she added, “Bit dae nae be sad. We hae a lot tae celebrate in oor lives. Nae least oor bonny bairns. Sae allow fowk ‘n’ frends tae pay thair last respects, say prayers, drink ‘n’ be merry, ‘n’ protect mah open casket, ’til it’s carried tae Kildonnan Graveyard th’ day efter.”22

Morag’s burial

On the morning of the burial, the men put the lid on Morag’s coffin and were about to carry it out of the cottage, when Ruaridh became angry.

“Keep awa’ fae her!” He shouted angrily.

Ruaridh easily lifted the coffin up on his shoulder, as he was a man of great strength. He carried it out of the croft, and started on the long walk to Kildonnan Kirk and graveyard.

The ‘pallbearers’ followed behind him. Others joined in the procession; soon, they were a procession of one hundred islanders or more.

The proud Scottish men of the island would rather die than show the womanly emotion of resorting to tears. But later, some of the island’s women said they had seen that Ruaridh’s eyes were moist with tears, as he walked along the road on the way to the Kildonnan graveyard.

He would bury her in the kirk, under the stone carving of Sheela na Gig, and near the graves of their children, Marion, Ewen, Ann and Mary.

Afterwards, some said he carried the coffin on his own shoulders because he was jealous of any man coming near her body. Others said it was an act of penance, like carrying a cross, a way of asking for forgiveness, as he had not always treated his wife in her lifetime as he should have done and in some way felt responsible for her early death. She was still beautiful even as she lay in the open casket during the wake. Many men and women had also thought this when they saw her lying there, pale and beautiful, as if sleeping. But none commented on this so as not to provoke Ruaridh’s ire.

Sources

- To avoid confusion – on her death certificate she is called ‘Sarah Campbell’ – if readers want to search this on ScotlandsPeople. ↩︎

- This may be an exaggerated scenario, but it is in the spirit of the advocate of naturalism Thomas Hardy. ↩︎

- Dressler, 2007: 127. ↩︎

- Dressler, 2007: 13-15. ↩︎

- Derek Cooper has written the book Road to the Isles (1979) in which he has published extracts of various accounts written about the Hebrides between 1770 and 1914, and included his own discussion and commentary. One such extract is taken from James Wilson’s “A Voyage Round the Coasts of Scotland and the Isles” (1842). The reference to ‘cannibals on Eigg’ is borrowed from this extract. Of course, our story about Morag takes place mainly in the latter half of the nineteenth century. In other words, I am diverging from historical exactness regarding dates as the author’s poetic licence to be able to include as much details as possible within a short narrative, without being enslaved by historical accuracy.* ↩︎

- Cooper. 1979. Pp. 90-91. ↩︎

- Dressler, 2007, p. 16. ↩︎

- Miller, H., The Cruise of the Betsey. Edinburgh. 1858. ↩︎

- https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/1969/may-9/layman-and-his-faith.html Read 6 April 2022. ↩︎

- Genesis 1:28. ↩︎

- Page 3 — Daily State Sentinel, 10 August 1859. ↩︎

- Dressler (2007). ↩︎

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-30890989 Read 6 April 2022. ↩︎

- I do want to die. I am still young. Who will look after you and all my babies when I am not here to take care of you all? ↩︎

- “I do want to die. I still want to live.” When my father died at the age of 53 years, my mother told me this has been some of his ‘last words’. This seemed a strong sentiment at the time, because my father was always a ‘strong man’ and never reverted to a call for sympathy – except during his final expiration. ↩︎

- Do not worry about us. You are not going to die. You are still young and beautiful. You will be forever young. You are just going to another place, called Tír na nÓg, the ‘Land of the Young’ – the realm of everlasting youth, beauty, abundance and joy. You will no more be paralysed when you come there because it is also a place of healing and health. And you will meet your children there, because they have passed to the other side. You will meet Marion, Anne, Hugh and Mary. ↩︎

- It lies somewhere to the west, where the sun sets. When you die in this world your soul will sail to the shore of the Great Sea, and from there you will ferried across the waves to the Isle of Tir-nan-Og. You will not need wind nor sail nor rudder. You will speed like a bird over the sea; and the wish of the Fate will guide you. ↩︎

- Songs of the Hebrides (Kennedy-Fraser, Marjory). 1909. ↩︎

- Inspired by Suzanne Vega, “In the Eye.” See YouTube clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAgBSq6oz3Y ↩︎

- Adapted from, Urquhart and Ellington, 1987, p. 38 ↩︎

- A Celtic wake involves allowing family and friends to pay their last respects to the deceased with an open casket, rituals, prayers, music, poetry, food, and drink. ↩︎

- But don’t be sad, we have a lot to celebrate in our lives, not least our bonny children. So allow family and friends to pay their last respects, say prayers, eat and drink and be merry, and protect my open casket, until it is carried to Kildonnan the day after. ↩︎