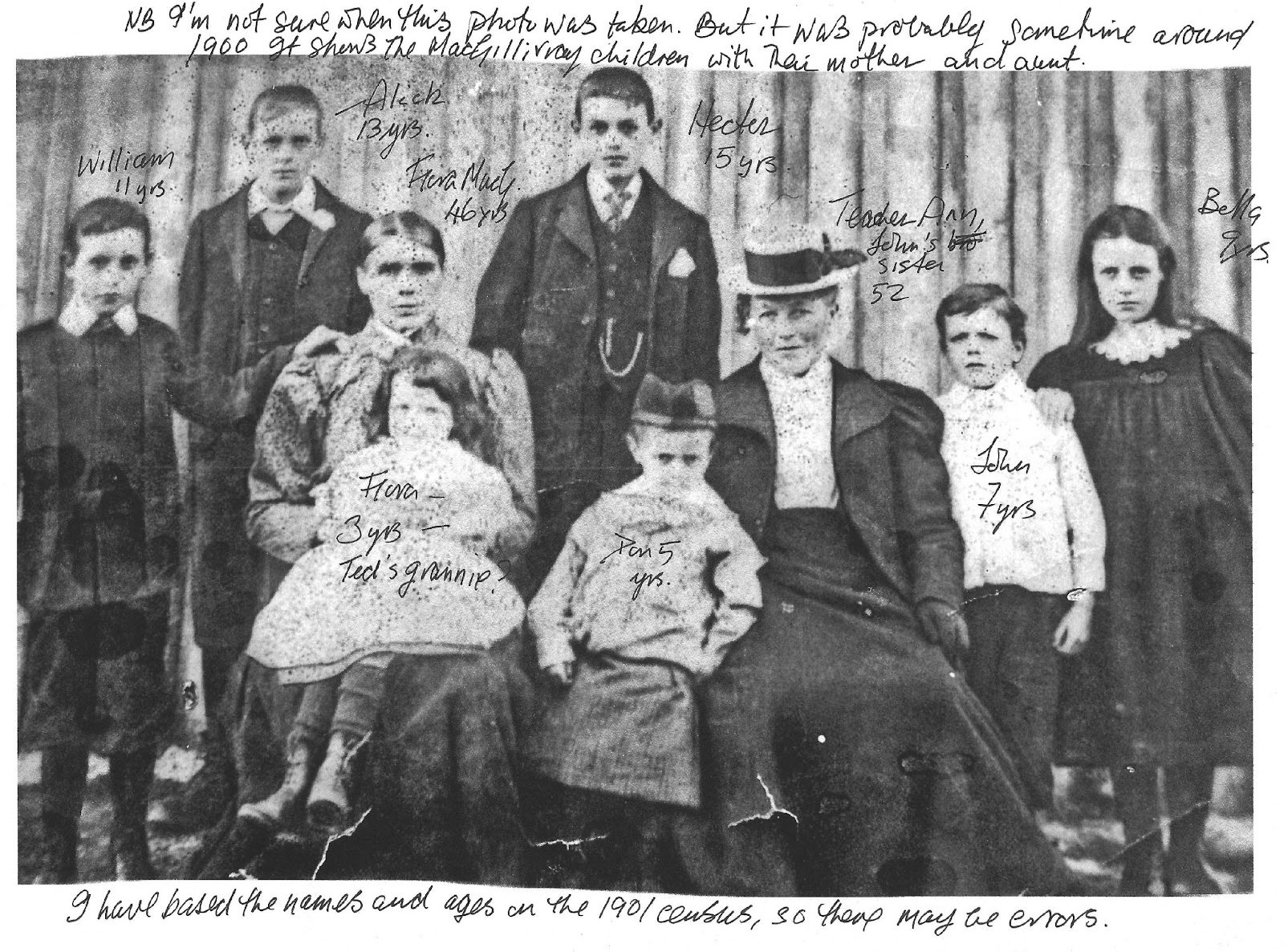

This chapter focuses on the children of Morag and Ruaridh and their fate as time went by.

The Yearly Hunt for the Fachach

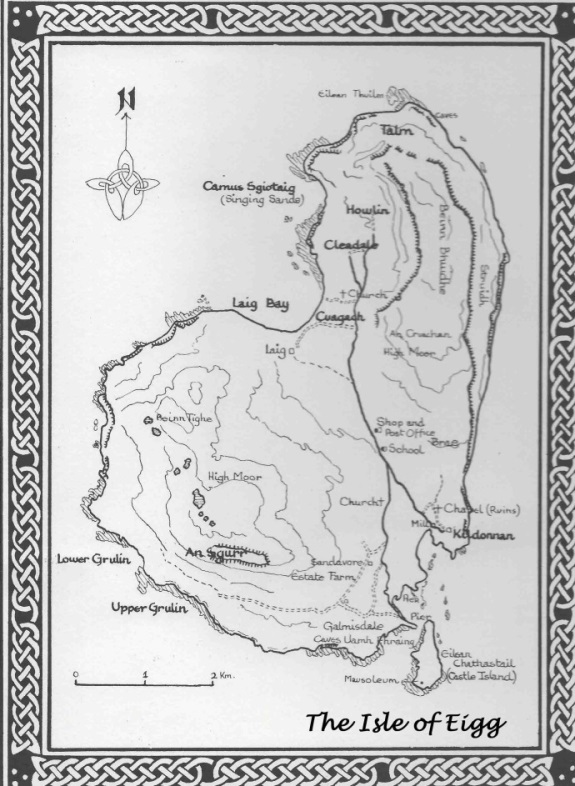

The Eigg people were called the fachach (Gaelic for the Manx shearwater birds), because they would harvest the birds from their nesting burrows in the cliffs of Eigg. The fat young birds were an important part of the islanders’ diet.

Every summer, on a specific day, all the islanders would descend to the treacherous cliffs of the island to collect the eggs and capture the young birds. The oily fachach — the young shearwater — were so fat that ‘you could just squeeze them and the oil would pour out of their beak’.1 The seasonal harvesting of the chicks of shearwaters provided the islanders with food and oil.

One of the dangerous cliffs was near Craignafeulac, near the Cathedral Cave and not far from the Campbell’s cottage at Galmisdale.

The young children, especially the young boys, were employed in hunting for the eggs and birds; their small hands and feet allowed them to climb down the cliffs to get the eggs and birds some hundreds of feet above the raging ocean and jagged rocks below.

They risked their lives for eggs and the young fat birds, as if food for the family was more important than their own lives. But it was also a matter of pride and bravery; the boys competed with each other to see who was the most daring. Ruaridh’s favourite son Ewen was one such boy. He was stronger, braver and more agile than boys of his own age; in other words, ‘like father, like son’.

Young Ewen has Fallen on to the Rocks! (1890)23

One day the cry went out, “Young Ewen has fallen on to the rocks!”

The little son of Ruaridh and Morag was barely six years old. He was his father and mother’s favourite child. Strong of body and fearless, he had inherited the attributes of his namesake, his grandfather, Ewen MacKinnon, and his father, Ruaridh. Thus, where the other children would not dare to go, he would climb down to the narrowest ledge on the rock face to stuff the young chicks and eggs into his sack. His brave exploits would be urged on by the men. But it was what he was best at that would be his undoing, that is his strength, agility and fearlessness.4

The mother birds had attacked him in unison as he tried to steal their eggs and chicks – pecking at him so he lost his grip and fell to his death below.

Afterwards, they managed to salvage his mangled body from the rocks and laid it out in the small cottage.

The cynical old aunt, Flora, said, “That’s one mouth less tae feed!”

Morag, his mother, wept silently. She had already lost one child, Marion, who died just a few days old. She felt her womb was shrinking.

The father, Ruaridh, didn’t say anything. He didn’t like that his older sister tried to harden their existence, but he had to admit that it was true – ‘one mouth less to feed.’ So he remained silent.

Investigation into Ewen’s Death

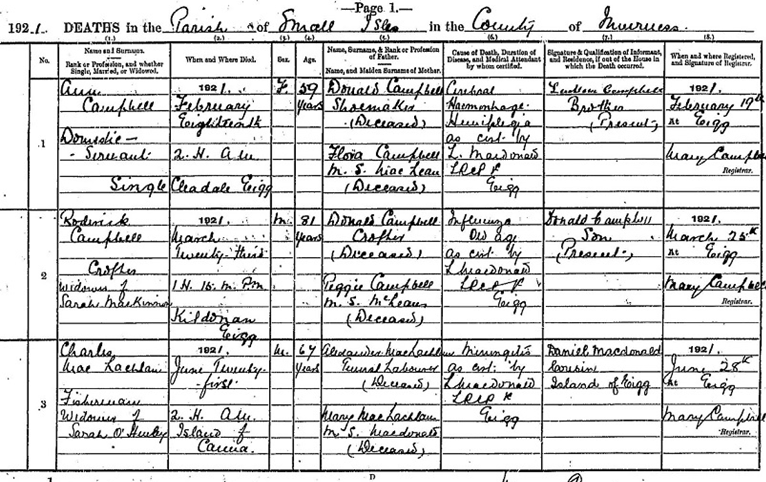

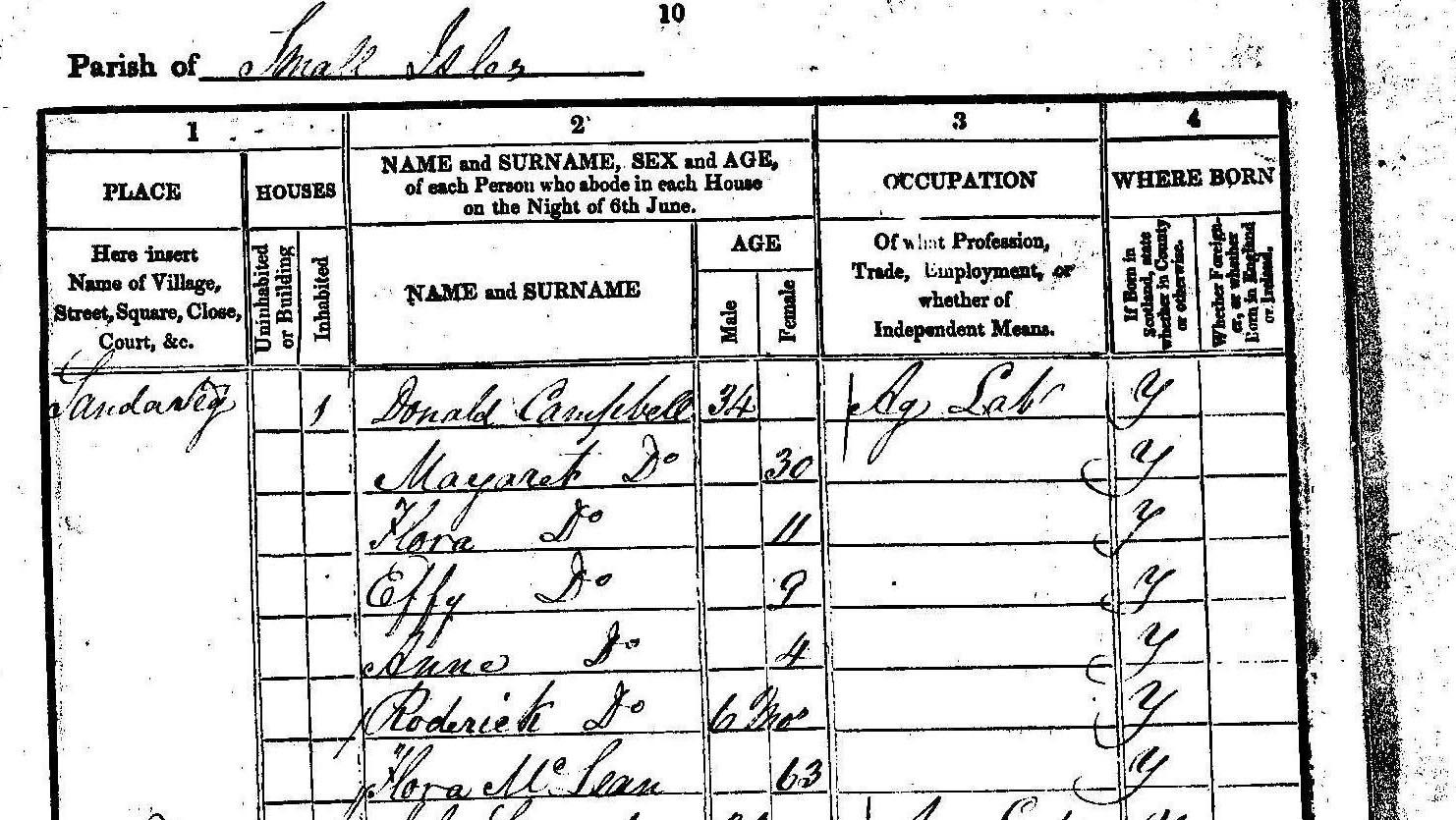

When children died on the island of some sickness with no doctor present, they would often write on the death certificate ‘cause of death unknown’. The authorities were not that interested in the lives of the poor people; if they were ‘interested,’ then this might prove costly because they would have to provide medical care and charity for the poor and needy. In other words, around this time (1890), the authorities provided little or nothing regarding welfare and medical care.

In The Cruise of the Betsey (1858), written some decades before, Hugh Miller noted that the authorities provided little charity for the sick and needy (pages 216-219). By 1890, not much had changed. Not long after this period, the government introduced various measures to help the ‘underclasses’. According to Dressler (2007: 127) “the Small Isles5 Parish Council for the Poor Law had finally appointed a medical officer in 1897, who was paid a yearly salary out of the rates collected in the four islands.”

Yet, the authorities didn’t want an anarchic and unchristian underclass, so they had to investigate the deaths of children that were not the result of sickness. Thus, young Ewen, who had been of little importance when living, now became the centre of attention for the authorities when dead. After all, things had to be done correctly!

Thus, officials were employed from the city of Edinburgh, hundreds of miles away, to investigate his death. A Doctor Carruthers from Edinburgh certified that Ewen had died from an ‘accidental fall’ at Craignafeulac. Ewen’s life had been of little interest to the authorities; his death, however, was of great interest and an added expense.6

The authorities noted that Ewen was buried at Kildonnan graveyard; he now shared his resting place with the Christianizing monk, St Donnan, and his 50 monks, who had been slaughtered by his Viking ancestors several centuries before.7

Ewen’s Burial in 1890

As mentioned, Ewen was buried at the Kildonnan churchyard. His mother Morag was now bedridden, as she had been these last three years, so she could not attend the burial. But the children in the family, and the old aunt Flora, all followed Ruaridh, as he carried the small coffin on his broad shoulders towards Kildonnan.

All the islanders that had taken part in the yearly hunt of the Fachach birds nesting on the cliff face near Craignafeulac also attended, so it was a long dismal procession to Kildonnan graveyard. The grave had already been dug. They believed the body of Saint Donnan lay deep and nearby. Saint Donnan had been beheaded by Ruaridh’s distant Viking ancestor.

As a tribute to the saint, the minister of the island, John Sinclair, said to Ruaridh that he should bury the hilt of the sword that had murdered Donnan. They were unsure of the exact location of Donnan’s grave, but they thought it was near the Campbells. So, the minister suggested placing the sword’s hilt in Ewen’s coffin to appease the saint. They felt that Saint Donnan had cursed the family and caused the island birds to attack the boy, so he fell hundreds of feet to his death on the jagged rocks jutting out from the sea below the cliffs, where the birds had their nests.

The minister felt it was inappropriate that his family kept this pagan tool of destruction in their possession and that it might explain why some of his children had met tragic and early deaths—that the hilt of the executioner’s sword of the Vikings was cursed. The minister had said that their second child, Morag, had died when she was only seven days old—that this was some curse on the family. Ewen was buried next to Morag’s grave.

After Ewen died, Morag had another child, whom she named after him (1890).8

In 1892, she gave birth to her ninth child Marion.9 Marion received the name of the second child that had died ten years before. But she was also named after her mother Morag, because Marion is the English equivalent of the Gaelic name Morag.

Morag’s Sadness Knows No End

Morag’s sadness knew no end. The young girls in the family had the job of finding shellfish on the beaches, and plants and berries in the fields and hills. They often made jam from the berries and ate it with oat cakes.

Picking berries and making jam – the death of Mary (1893)

In 1893, the seventh child, Mary, was five years old. She had been picking berries down in the fields with Siùbhan, a friend who lived close by. They picked what they thought were blackcurrants and made a fire, boiling the berries with water. However, they were not blackcurrants but extremely poisonous belladonna berries, also known as deadly nightshade. It has a similar appearance to blackcurrants.

Siùbhan vomited and survived, whereas Mary died from eating the berries. Mary’s death, unlike her brother Ewen’s, didn’t need an inquiry by the authorities. They just wrote on her death certificate, cause of death “unknown.”10

The death of Anne (1894)

Anne died at 16 years old. The death certificate reported that she had died from a “supposed bad cold”, with no medical attendant present. A “bad cold” could be anything from pneumonia to influenza.

Some time had passed since Morag had become ill, and, as noted, Ruaridh would often console himself by visiting the old tavern and drink whisky with his cronies after a hard day’s work.

Morag was now bedridden, and she’d lost the spark of life. She became even more saddened by the recent deaths of her grandparents, Donald and Mary MacKay.11

As mentioned, Morag wasn’t able to work in the fields anymore, or care for her children, although she was sometimes able to do some sewing, spinning and weaving, as she still had the use of her arms.

But she was still essentially a ‘woman’. Because what is a woman? A beast of burden? No! A slave in the fields? No! A man’s housemaid? No! Without women, there would be no men.12

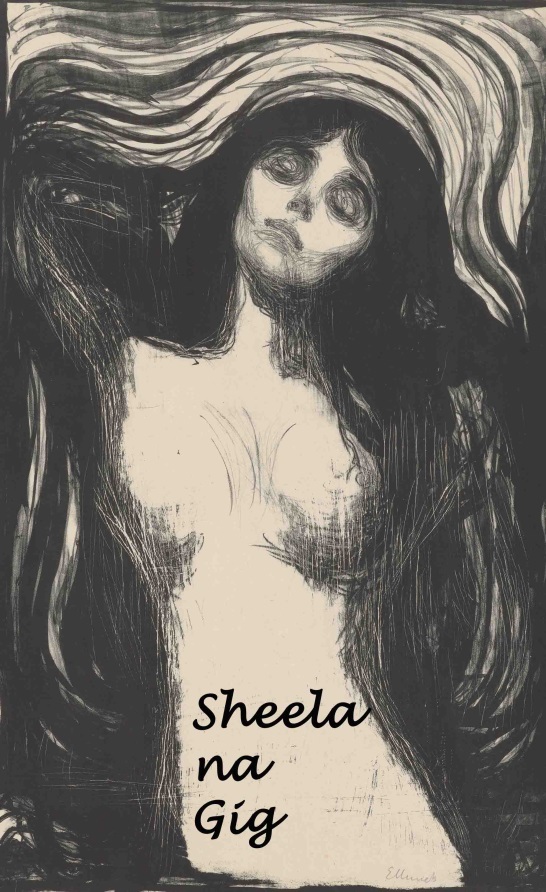

As mentioned, Morag often despised Ruaridh’s nightly intrusions. But at other times, she thought, “This is my role in life now. I may be paralysed, but I’m still a ‘woman’. I haven’t chosen this life – but this is my life for better or worse.”

So, although bedridden and sick, she still had beautiful child-bearing hips. She had red lips. She had a womanish charm.13 She sometimes offered these charms to her husband when he returned drunk from the tavern.

Sometimes, she would lie on the bed naked, offering herself up to him and saying, “Dear, I’m all yours.”

Although drunk, Ruaridh would sometimes reply, “Sheela-na-gig, Sheela-na-gig,” meaning that it was unwomanly of her to exhibit herself in such a way, and offer herself so freely to him. But despite her ‘violation’ of his ideas about how a woman should behave, it would not deter him from taking her, so she still felt like a ‘woman.’ Although bedridden, she gave birth to four more children.

As noted, after Morag became paralysed around 1887, she gave birth to more children: Mary, who died from poisoning; Ewen; Marion; and John, who was born the same year Morag died. John died two years later, in 1897, aged two. In other words when she was bedridden, three of her children died. So every year of her eight bedridden years would be marked, more or less, by either the birth of a child or the death of a child, with Anne, Mary, and Ewen being the three children that died.

Sources

- Dressler, 2007: 112-113. ↩︎

- See death certificate: Scotland’s People: Hugh Campbell: 20 July 1890, ‘Registrar of Corrected Entries’. See also: “Eigg and Its People” ↩︎

- See death certificate: Scotland’s People: Hugh Campbell: 20 July 1890, ‘Registrar of Corrected Entries’. ↩︎

- Zapffe’s paradox: “It’s what you are good at that will be your downfall.” ↩︎

- The Small Isles: Canna, Rùm, Eigg and Muck. ↩︎

- See Scotlandspeople and https://macgillivray-culloden.com ↩︎

- An interesting point here is that the place of burial was not normally noted on death certificates. But because this was an ‘investigation’, or so-called ‘Register of Corrected Entries’ it was noted ‘Burying place – Kildonnan burying ground’. We can perhaps assume from this that all the Campbells were buried at Kildonnan graveyard. Kildonnan graveyard is quite small – so one wonders how hundreds or thousands of people can have been buried there.

I visited the graveyard around 2006-8 – but I could not see any headstones dating back to the nineteenth century – except perhaps the burials of more ‘notable’ people. So it might have been the case that they were buried without a headstone. The only family headstone I found was the stone of Ruaridh’s son Donald and his wife Janet, and their children – dating from the mid-twentieth century. ↩︎ - The birth of the eighth child Ewen 1890 (written as ‘Hugh’ on the birth certificate). ↩︎

- My grandmother, Morag Campbell, who provided many of the oral sources as told to her daughter, my mother, Rhoda MacGillivray. ↩︎

- My mother, Rhoda MacGillivray, told me many ‘stories’ – which I often took with a ‘pinch of salt’. That is oral stories that her mother had told her regarding the early and accidental deaths of her siblings. The story of Hugh (Ewen) falling from the cliff sounded highly fictional. But searching ScotlandsPeople, I actually found the evidence written on Hugh’s death certificate – ‘accidental fall from cliffs at Craigfeulnac’.

So although Mary’s death certificate does not record that Mary was ‘poisoned by berries’ – there is no reason to believe that this ‘story’ is not true. Moreover, the authorities would want to avoid the extra cost of an ‘investigation’.

In Ewen’s case, his dramatic fall from the cliffs demanded an investigation, whereas, Mary’s less dramatic death could be written off as ‘cause unknown’.

This is almost comical from a ‘sick humour’ point of view as most of the islanders died of ‘causes unknown’, as there was no medical attendant; or they wrote ‘supposed’ bad cold, and the like, as it was not attested by a medical attendant. ↩︎ - Donald lived to the ripe old age of 81 (d. 1881). The cause of death is ‘palsy’(3 years). This is another one of these old medical terms used on death certificates meaning some kind of paralysis. His wife Mary died three years later in 1884, aged 80. Cause of death: ‘Asthma’ (several years) – and ‘catarrh’ (one week). Her son Roderick signed the death certificate with an ‘X’ – so both he and his parents were illiterate. (ScotlandsPeople) ↩︎

- Simone de Beauvoir. https://www.bartleby.com/essay/Simone-de-Beauvoir-Feminism-and-Existentialism-PKRJTKADJ3DQ Read: 5 April 2022. ↩︎

- Inspired by “Sheela-Na-Gig” by P.J. Harvey. See also YouTube clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xkS_R7RDuMc ↩︎