Note: This is the post-script and the final chapter of the Tale of Morag. To read the story from the beginning, start at the Preface.

Apology

I want to take this opportunity to apologise to Morag and her children for being inadequate in trying to tell the Tale of Morag through this postscript.

Morag and her children were buried at Kildonnan graveyard. Their graves soon became overgrown and only visited by the grazing sheep of Kildonnan Farm. The lives, loves, and sufferings of mothers and children were soon forgotten over the years. The only thing that remains of their lives today is this story.

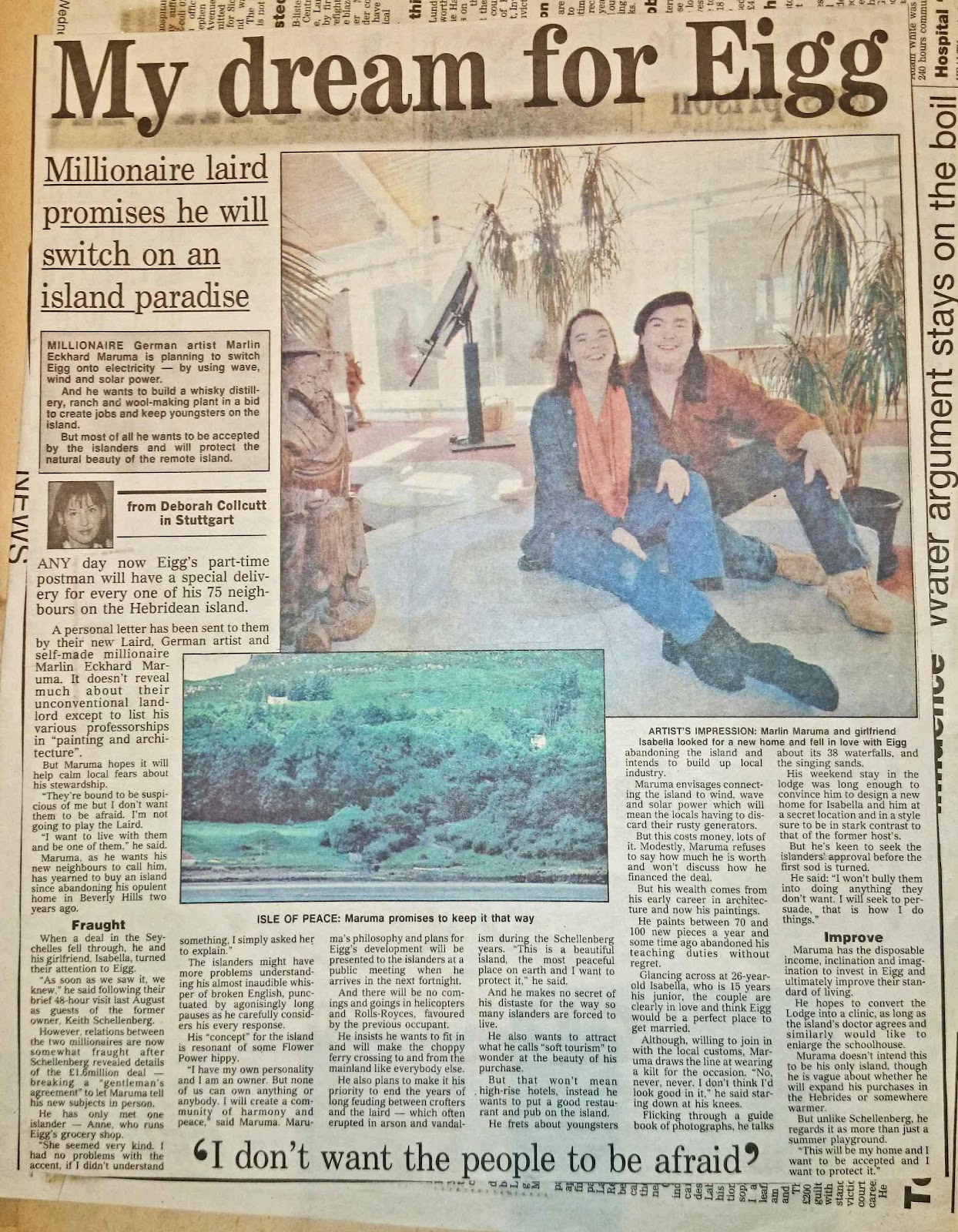

A New Laird

Two years before Morag’s death, a new laird, Thompson, took control of the island in 1893. It had previously been ‘owned’ by Dr. Hugh Macpherson. As mentioned above, Thompson was enormously rich because of his illegal gun-running activities. He moved to the island and took residence in the large mansion reserved for the laird. However, this mansion was near the crofts of the poor islanders at Galmisdale, where Ruaridh and his family lived.

Laird Thompson would often go walking with his dog and gun. He would also hold shooting parties for his upper-class English friends. They liked to visit the ‘wild’ lands of Scotland to hunt grouse and other wildlife, so they had exciting stories to tell their aristocratic friends when they returned to ‘civilization’ in the autumn; that is, their residences in London, such as Regent’s Park and Kensington.

The Gaelic ‘natives’ were perhaps an ‘amusement’ for these aristocrats. In reality, their sheer poverty and disease were frightening; poor, ragged, unwashed children running around barefoot, dying at a young age from accidents or infectious diseases such as tuberculosis. The latter caused Laird Thompson to remove these poor people from his sight. Thompson did not want to infect his guests with the infectious diseases of the island’s poor. He sought consolation in the Bible regarding his new plan. After all, in the days of antiquity, lepers should be kept in camps isolated from others. So why not isolate the poor ethnic Gaelic population on the other side of the island out of his sight? After all, it was ‘his’ island!

As mentioned before, the laird of the neighbouring island, the Isle of Rhum, had evicted every single inhabitant from the island: 400 people in all—the old, the young, and the feeble. Thompson’s gamekeeper suggested they should do the same: cleanse the island of this detritus Gaelic ‘filth.’ However, the Scottish government was introducing new reforms aimed at protecting the rights of tenant farmers and crofters.

Thompson did not want to attract public attention. His fortunes had been amassed by more or less illegal means, so he needed to avoid public scrutiny. Besides, despite his illicit past, he was not a hard-hearted man like the Laird of Rhum. The Laird of Rhum had instigated eviction from the island in quest for profit. This was not necessary for Thompson, as he was enormously rich and could buy islands like Eigg ten times over. He was not motivated by profit.

Moving House, the New Crofts at Cuagach

In other words, despite his illicit activities and dislike of the poor, Laird Thompson was not a vindictive man. It was easy for him to invest in building new crofts on the other side of the island so the poor crofters would be ‘out of his sight’ and ‘out of sight’ of his ‘Regent’s Park’ friends.

So it was done! Thompson ordered the building of new crofts on the other side of the island at Cuagach. Ruaridh’s family was ordered to move. Of course, Ruaridh was not able to discuss this with the Laird. The Laird spoke no Scottish Gaelic, and Ruaridh spoke little English, so it was left up to the gamekeeper, fluent in both Gaelic and English, to explain to Ruaridh the new situation. Perhaps Ruaridh might even gain something from this new situation?

The building materials for the new cottages were ordered. The cottages would be far superior to the old ones. The roofs would be Ballachulish slates brought by the puffer boat to Laig Beach. Five identical houses represented the height of modernity and an undeniable improvement in living conditions with their two upstairs bedrooms, parlour, kitchen and boxroom downstairs, wood panelling and cast-iron range!

Despite the improvement in living conditions, Ruaridh was unhappy because of his job as a ferryman. It would be more difficult for him to monitor when the ship arrived, as he would now be living on the island‘s north side while the post and goods arrived on the south side. Absurdly, in order to solve this problem, he purchased a new so-called ‘safety bicycle.’ But perhaps Ruaridh had been fooled by the marketing: the bike without gears could not traverse freely from the north to the south of the island because of its hilly interior; thus, he would have to push the bike up the steep inclines.

But at least, Ruaridh gained local fame as the first Eigg man to adopt this ‘modern technology’ around the turn of the century! Little did he know that these same innovative forces of a new economy would be responsible for obliterating the centuries-old Gaelic culture, language, and heritage—not to mention the dispersal of his children and grandchildren away from the Isle of Eigg.

After two or three years, the new crofts at Cuagach had been built. The gamekeeper ordered Ruaridh and the others to demolish the Galmisdale crofts and use the stones to build a wall.

Some years after the death of Morag, the family moved to the new croft built by the new laird, Thompson. The lairds rarely treated their tenants with dignity. But perhaps Thompson was the exception—we can’t know his motives—but the fact is that the Campbell’s standard of living considerably increased when they moved into their new croft in Cuagach.

mortuis nihil nisi bonum

The Latin phrase mortuis nihil nisi bonum means ‘Of the dead, say nothing but good’ (as they are unable to justify themselves). I will have to ask forgiveness from the ‘dead’ (my ancestors) for ‘speaking ill of them,’ as many details in this story are ‘fictions’ but nevertheless based on assumptions that emerge from the sources. My defence is without these stories, they would be completely forgotten. Some may say that it is best some things are forgotten, when it comes to light that one’s great-grandmother was an illegitimate child! Or that one’s grandmother was prone to using the tawse to punish her children.

However, I don’t agree. Everyone has the right to have their story written for posterity – even if it is not absolutely true to the facts. After all, no ‘stories’ are absolutely true!