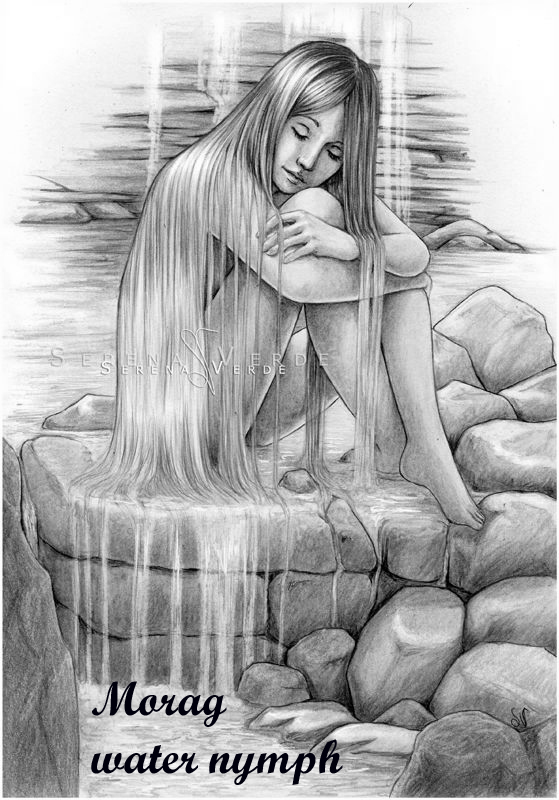

Morag Singing Tir nan Og at the Burn

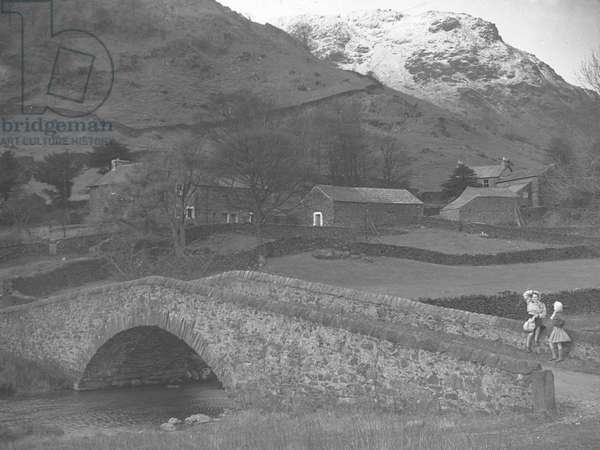

Ruaridh was going back to the cottage after working in the fields. When he crossed the bridge over the burn at the bottom of Kildonnan Hill, he heard a young girl singing ‘Tir nan Og’. The song was about the other world (‘the-land-of-the-forever-young’). The singing also sounded otherworldly, like the singing of a fairie.

The roar of the waves, plaintive their sound,

As they chant in my ear thy praise,

The song of the bens, the fountain and stream,

With thy music downward flow;

By day my witchment ever thou art,

Thy longing eternal me wounds,

And by night thou art ever my dream,

Tir nan Og1

He became wary. Fairies could be benevolent but they could also play tricks on you. There was a belief among the islanders that a spirit haunted the bridge over the burn at the bottom of Kildonnan Hill.2 Ruaridh used to laugh at his friends when they told stories of the fairies, spirits, and ghosts of Eigg. But still, he was not sure. He plucked up courage and followed the sound of the singing upstream.

“It was true!” he thought to himself. He could see a young fairie bathing in the burn as he went closer.

When he was a young boy, his mother, Peggie, had often told him bedtime stories of the water and wood nymphs on the island. Of course, even as a child he thought these were just fairy tales. But now, the fairie on the bank of the burn indeed looked like a water nymph from his mother’s stories.

Ruaridh meets Morag at the Burn near Kildonnan Hill

One day, while Morag was bathing at the burn, she saw a tall male figure in silhouette, the sun behind him. She recognized the silhouette – no other man on the island had such a tall and strongly-built stature. It was Ruaridh Campbell or, as he was known on the island, Ruaridh Ruadh; translated into English his name means ‘Roderick the Red’.

She had seen him before, but they had never talked. He was a mature man in his twenties — the ferryman of the island — and she was just a little girl in his eyes. As he approached closer, she felt a surge of energy that felt foreign to her. It was quite strange but also pleasant. She felt her breath quicken and her cheeks flush.

Her grandfather had told her stories of the Campbells — that their ancient kin had been fierce Viking warriors. It was rumoured that Ruaridh’s distant Viking ancestor was the same Viking chief that had ransacked the Kildonnan Church on the island. More than that, he also beheaded St. Donnan and his fifty-two monks. It was also rumoured that Ruaridh had in his possession the hilt of the sword that had beheaded St. Donnan. It had been passed down through the generations.3

Of course, Morag thought the whole thing was just a gruesome bedtime story that her grandpa told her to scare her. But when she saw his visage approach, the story started to make some sense. He was an impressively tall man with broad shoulders, massive red hair, and a large red beard. In fact, he was so tall that even if she stood on her tiptoes, and reached her hands high up in the air, she’d never be able to reach up to touch his mass of red hair, which now glistened in the setting sun.

She became mesmerized by the visage — not because she saw a ‘man’. After all she was still a little girl. She was mesmerized by the fact that he was not like any other man in the township or on the island. So her grandpa’s story about Ruaridh being a descendant of the Vikings that had ruled the islands centuries before was true.

However, he wasn’t so much a character from the epic about the Viking warriors; it was like he was the reincarnation of that epic hero who had sailed over the seas in his longship from the lands of the North and conquered the islands of Scotland some centuries before. Although the Vikings were brutal against their enemies and the lands they conquered, legends said they treated each other like equals and reached agreements together. The Vikings were pagans, but believed all free men were born equal.4

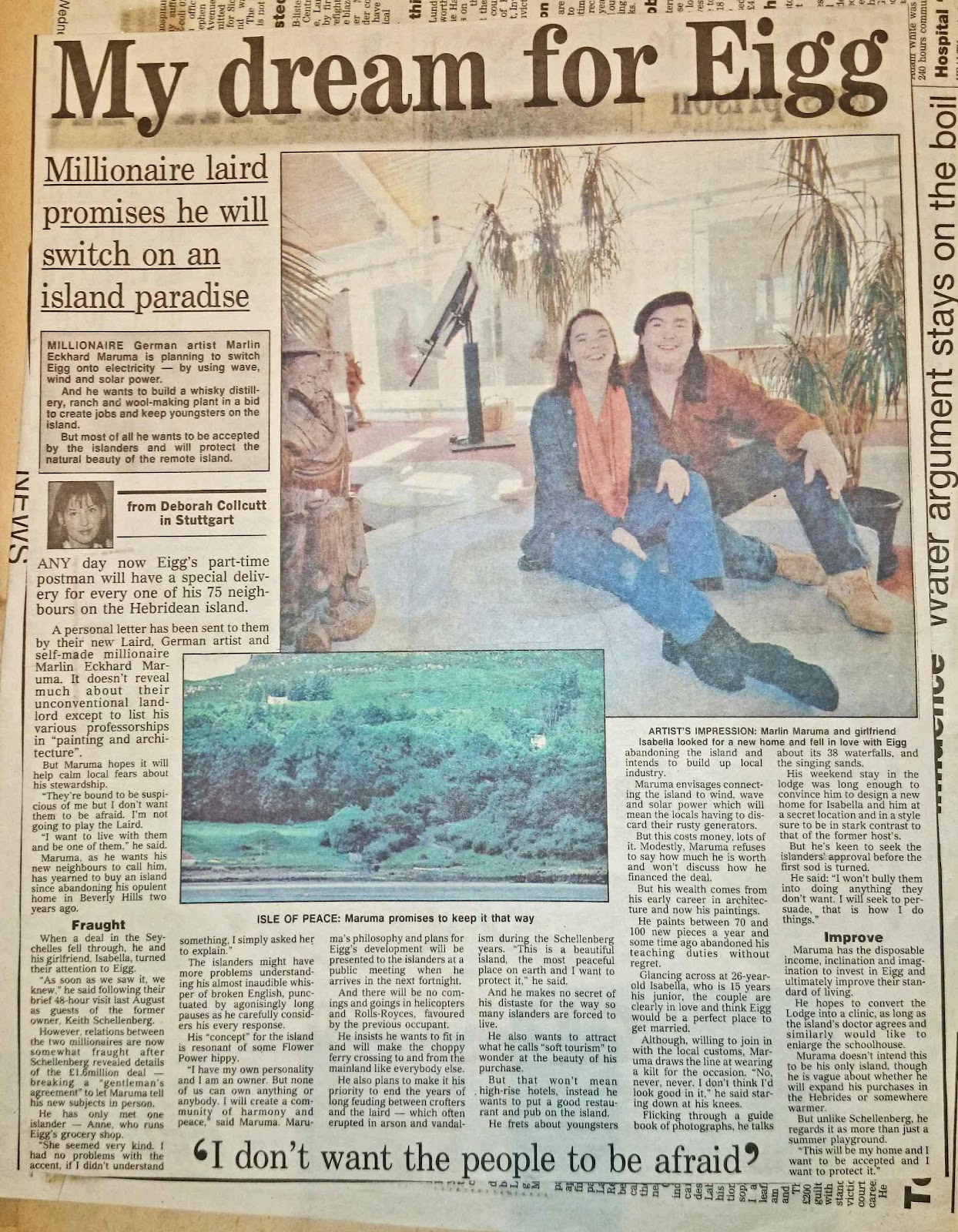

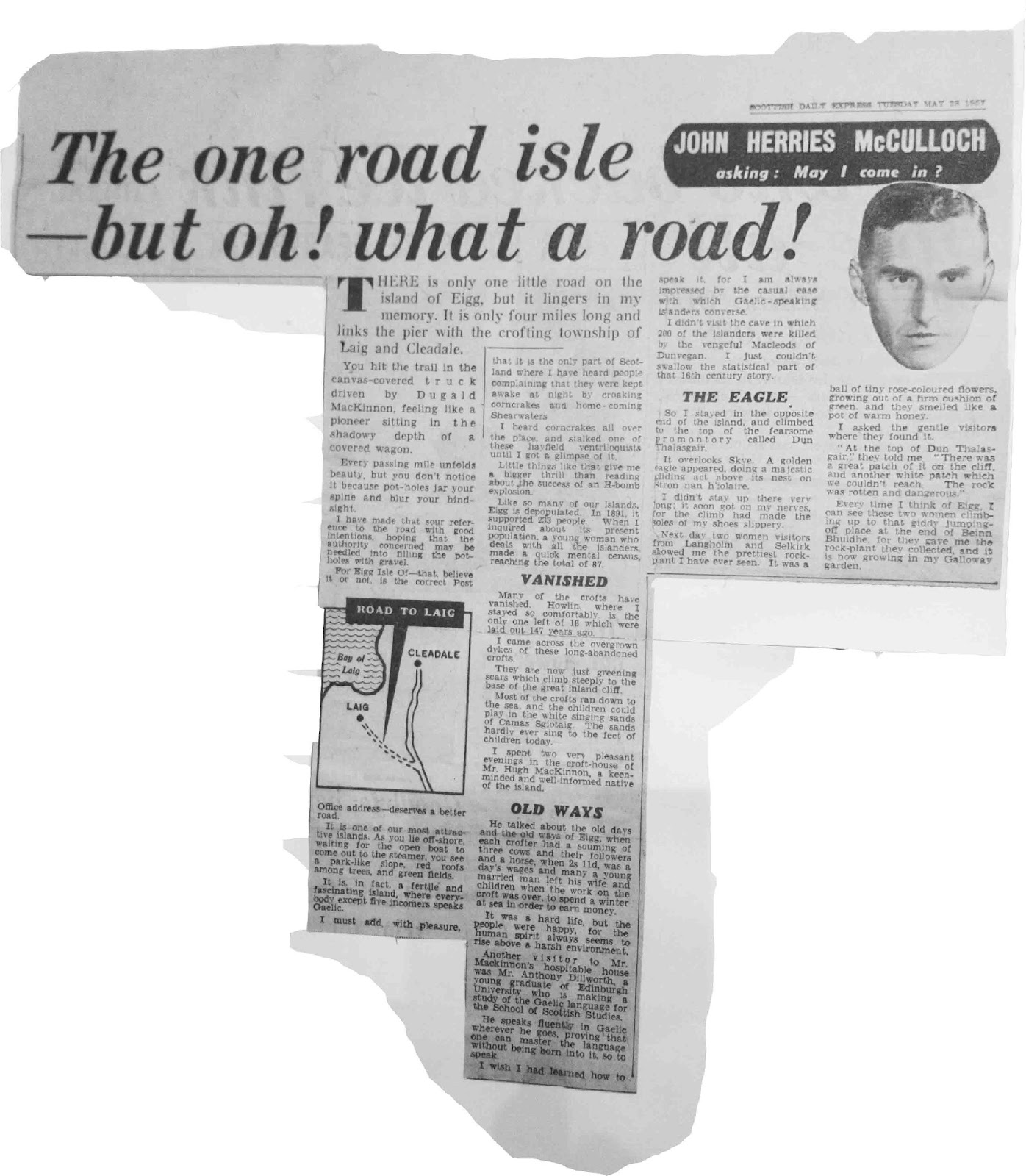

Since those times, the Scottish isles and highlands have degenerated under the rule of the Christian English-speaking lairds and their oppressed Gaelic-speaking crofters. The lairds professed themselves to be Christians but certainly did not follow the teachings of Jesus that all men and women are equal. Whether they be Gaelic-speaking or English-speaking, crofter or laird, man or woman: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”5

Ruaridh was coming very close now – he was almost upon her. Despite his imposing stature, he had a very mild demeanour. He didn’t glare at her as some men did or smirk at her as did many of the older women. He stood calmly before her and smiled gently. She felt overpowered by his presence but managed to demurely return his smile.

Ruaridh felt like a fool when he realised the fairie was just the little girl who lived in the neighbouring croft.

“Whit urr ye daein’ ‘ere doon by th’ burn mah wee lassie, if ye dae nae mynd me asking? And what’s that song yer singing?”6 he asked her.

Morag blushed and cast her eyes to the ground. She had never had such a close encounter with her neighbour before. Flattered that he should take an interest in her, she almost lost her breath and was only able to barely answer his questions.

She answered in a soft young girl’s voice, not daring to look him in the eye, “I’m juist waashin th’ shirts o’ mah grandpa.7 An’ the song is ‘Tir nan Og’. Ah lik’ tae sing it while I’m waashin claes ‘ere by th’ burn, under th’ huge rock, th’ An Sgurr. Th’ sound ‘n’ roar o’ th’ waves fae th’ sea doon by th’ beach ur mah chorus.”8

“Aye, it’s a bonny song. Bit it’s nae as bonny as th’ wee lassie singing it.”9 He said to his own surprise, as he rarely paid complements to young girls; but it was as though the words had sprung forth from his mouth by themselves.

Morag’s damask white cheeks turned as red as sweet apples. She lowered her eyes out of shyness and embarrassment at his words.

Ruaridh had become entranced by the vision he saw before him – the little MacKay girl was something between a girl-child and a young woman. She was evolving into a beautiful woman like a blossoming rose. He wanted to be a part of her journey.

Morag was not only washing her grandpa’s shirts, she had also bathed. The only thing covering her childish innocence was her long hair and a scant undergarment. Ruaridh averted his eyes out of respect for the little girl. However, he couldn’t help but glance at her nymph-like forms, which he could see through the translucent undergarment.

Although Morag was just a young girl and he was a much older man, she saw something in his benevolent smile; intuitively, she thought this was someone who could be a friend and help her and her family. Despite her young years, she could also see that he was looking at her as if ‘enchanted’. She instinctively thought she might turn this to her advantage in the future. After all, he was the strongest and most respected crofter on the island. In her young girl mind, she thought unconsciously, “Here is perhaps a man that can erase the shame from me and my mother.”

But who wouldn’t be bewitched by such a water fairie? Even the gossip, the spinsters and meddlers, could not deny that she is truly a beautiful sight to behold. She was the epitome of young beauty. Her hair was as black as the volcanic rock of An Sgurr. Her skin was as white as the snow that covered the erect rock in winter. As Ruaridh approached her, the setting sun caught tints of blue and red in her otherwise jet black wavy hair. It fell wildly and luxuriantly over her shoulders and down her back. Those locks corresponded with her gypsy eyes, which were also of the deepest jet.

As their eyes met, he felt his heart skip a beat. She was such a virgin beauty, he thought to himself. He was hypnotized. He knew she was a ‘bastard’ child, born out of wedlock. But this seemed to add to her worth in his mind. He wanted someone to protect and covet.

The older women on the island and some of the men looked at illegitimate children as if they had some contagious disease; that association with them could result in them being ‘infected’. This was the view of the church ministers—that illegitimate children are the evil spawn of whores, scolds, and witches. They believe only God can consecrate a relationship between a man and a woman. Everything outside God’s consecration of marriage is the work of the devil, and the illegitimate child is more ‘evil’ than the parents.

In other words, Morag felt everyone on the island despised her. So she thought of herself as ‘ugly’. In fact, many people had said that her jet black wild hair was a clear sign that she was descended from the evil ‘Black MacKinnons’. Rumour has it that her father, Ewen MacKinnon, was descended from the murderous black gypsies of Ireland.

The ‘Black MacKinnons’ had been exiled from Ireland because one century or so before, a hot-headed member of the MacKinnon clan, ‘Black Ewen’, a man of great strength, had slain Donald MacLeod, the foppish fair-haired son of the local laird, in a sword fight.

At a local feast, Donald had ‘grabbed’ one of the MacKinnon women, dragged her away, and violated her. So for Ewen, it was a duel of honour and retribution. However, it wasn’t really a ‘duel’ as such, but more of a ‘slaughter’. Ewen had severed Donald’s leg with the first thrust of his short sword, so he fell to the ground and bled to death. Ewen spat on him shouting, “Die ye dirty Macleod. Ye abuser o’ guid wimmin!”

But the islanders of Eigg had long since forgotten that Ewen had been protecting the dignity and honour of a kinswoman; the only thing they remembered from this story was that he was an Irish ‘gypsy’ and a ‘murderer’ who had been exiled.

So Morag was twice cursed, a bastard child, and her family descended from ‘black’ murderous Irish gypsies. In other words, she felt twice ugly and could never imagine that anyone would look at her as beautiful or that her beauty one day might entrance a man.

Morag returned to the burn the next day to do her chores, as she always did. She stayed a little longer than usual, hoping to see her imagined ‘protector,’ the gallant red-bearded Viking. This idea had formed in Morag’s mind—perhaps this ‘Viking’ could remove her shame and help her and her family. Thus, she waited for ‘Ruaridh the Red,’ the strongest man on the island.

Her grandfather Donald had also told her about the feats of Ruaridh. In the Island games, he would beat all the other men at various sports, such as casting a large stone of 25 pounds at a distance of 55 feet, at least 15 feet more than his nearest rival. He wasn’t a violent man, but was reputed to be able to fight several men at the same time, beating them to a pulp, if his honour was at stake.

So she waited for him with the absurd idea that he could be her ‘saviour’.

But all her waiting was in vain.

Sitting outside her cottage at night, with the stars in the sky twinkling as if in harmony, and with the waves washing up on the beach in the distance, she daydreamed about Red Ruaridh, but he never appeared again.

She was just a young girl of thirteen years —so it was perhaps preposterous that she was having such young-girl fantasies about this grand man, as he was much older than her. But she had little hope to cling to in her miserable life. She could still recall his ‘benevolent’ look, although she didn’t fully understand what it meant.

As time wore on, and he did not appear, she resigned herself to the fact that no one would want to befriend a ‘shamed’ child. Nevertheless, she still hoped and prayed.

The days and weeks passed, until they became months.

Sources

- “The Songs of the Hebrides.” Marjory Kennedy-Fraser. https://electricscotland.com/poetry/songshebrides.pdf Read 1 April 2022. ↩︎

- Adapted from, Urquhart and Ellington, 1987, p. 38 ↩︎

- Generations back, the Campbells were descended from the Macaulay’s. The Macaulay’s were in fact descended from the Norse Olafsons (‘Macaulay’ is originally a Norse name and means ‘the son of Olaf’). The ancient member of the Viking clan that slew Donnan was called Rø̄rīkʀ Olafson. Rø̄rīkʀ is Old Norse for the Gaelic Ruaridh and the English Roderick. The hilt of the Viking sword that was owned by Ruaridh was inscribed with the Runic letters of his distant ancestor RO. Ruaridh was thus named after his distant ancestor, Ruaridh Olafson – the Viking who slew Donnan in AD 617 (Magnusson, Magnus. The Oxford History of the Vikings, 1923. Oxford). Written 1 April 2022. ↩︎

- Of course, the Vikings had slaves who were not considered as ‘equal’. However, all ‘free men’ of the Vikings would gather in their communities to make law and to decide cases in a meeting called a Thing. In certain spheres of life, Viking women had more ‘freedoms’ than in Britain 1000 years later. For example, women in Viking Age Scandinavia could own property, request a divorce and reclaim their dowries if their marriages ended. https://www.history.com/news/what-was-life-like-for-women-in-the-viking-age Read: 1 April 2022. ↩︎

- Galatians 3:28 ESV / 21. ↩︎

- What are you doing here down by the stream my little girl, if you do not mind me asking? ↩︎

- I’m just washing the shirts of my grandpa. ↩︎

- The song is ‘Tir nan Og’. I like to sing it while I’m washing clothes here by the stream, under the huge rock, the An Sgurr. The sound and roar of the waves from the sea down by the beach are my chorus. ↩︎

- Yes, It is a beautiful song. But it is not as beautiful as the little girl singing it. ↩︎