Chapter 1, Post #4 on Isle of Eigg

Memories

Memories are significant in our lives because they allow us to reflect on our past. They allow us to relate this to the present and the future with the hope of growing and learning to be better people. As mentioned, this book is mainly based on the memories of my mother, Rhoda Harkness, nee MacGillivray, and documents acquired from http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/. We have birth, marriage, death certificates and censuses (refer to separate Appendix). It is also based on artefacts collected by my mother, secondary sources, such as Camille Dressler’s , Eigg – The Story of an Island (2007), and other books and websites.

Methodology

It is perhaps unusual to talk of ‘methodology’ when writing a family history. However, I have already referred to the use of primary and secondary sources, and the interpretation and discussion of these. This is a method used in various fields such as literature and history. Of course, there are many ‘methods’ within various fields.

Regarding sources, many of these are unreliable, such as oral accounts, or historical descriptions stretching far back into the past. Official documents are on the whole reliable, but only provide the ‘bare facts’. Consequently, I intend to introduce a ‘new’ method, which I term ‘historical scenario – semi-fictional documentary’. In other words, a scenario and fictionalized account based on primary sources (both written and oral), and secondary sources.

‘Scenario-thinking’ is usually associated with possible outcomes in the future. Of course, ‘historical scenario presentations’ are nothing new. It can be found within the genre of ‘historical fiction’, such as in the novels of Sir Walter Scott (Rob Roy) and Aldous Huxley (The Devils of Loudon). These types of novels are often called ‘non-fiction novels’. But of course, due to the subjective perspectives of the authors they become ‘fiction’. On the other hand, one could perhaps say that ‘all history is fiction’, as the author’s imprint is always visible.

Others have noticed this, and the above adage is often accredited to Maximilien Robespierre. He said “Our revolution has made me feel the full force of the axiom; that history is fiction and I am convinced that chance and intrigue have produced more heroes than genius and virtue”. However, as far as I know, these authors (Scott and Huxley) did not mention the fact that their novels were ‘fictionalized’ scenarios. (Although I have not done research here, so this is just an assumption).

So in order to try and ‘spice up’ the often ‘dry’ descriptions and stories here, I will include, as mentioned, six semi-fictionalized stories and one poem.

Primary and Secondary Sources

In academic terms, the book is based on an interpretation of primary sources, and a reference to secondary sources. Primary sources provide raw information and first-hand evidence. Examples include interview transcripts (such as interviews with my mother), letters, photos, newspaper clippings, paintings, first-hand accounts, and so on; and, in our context here, official documents, such as birth, marriage and death certificates, and censuses. Secondary sources provide second-hand commentary, usually from other researchers and writers. Today, this often involves searching the Internet. When using primary sources one attempts to interpret the meaning that is inherent in the primary source.

ScotlandsPeople

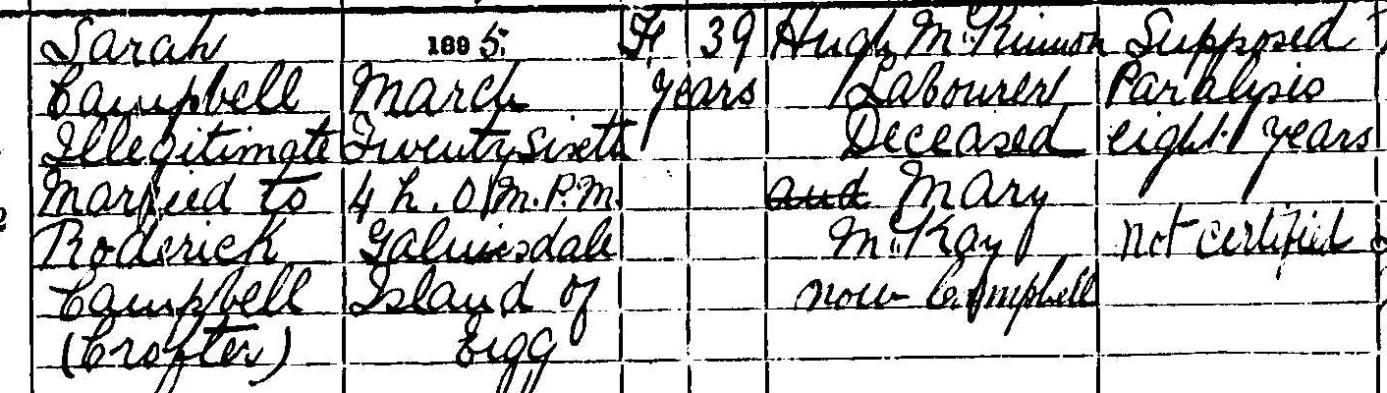

“ScotlandsPeople” has search facilities and provides access to a vast number of documents, and isn’t too expensive to use. It also provides tips and help, such as information concerning name variations. This was useful when tracking down my great grandmother Sarah Campbell (nee McKinnon); she was called Marion, Christina, Peggie and Morag!

Information after 1855 is fairly straightforward to access, because of a government reform involving public records. Using this website and Internet search engines, I have managed, more or less, to trace the family lines of all four grandparents back to the early 1800s. My mother, Rhoda Campbell Harkness, was also a great help in providing assistance over the telephone and in person.

As far as I can remember, I started searching ‘ScotlandsPeople’ more than twenty years ago; but over the years, I have only done this intermittently. Your searches are always ‘incomplete’. Ironically, with the development of artificial intelligence (AI), such records may in the future perhaps be more efficiently investigated. Aat this point in time, I have depended on my own independent manual searches, and not used so-called professional agents.

Eigg and James Campbell

In the hundreds of documents that I have downloaded from ScotlandsPeople regarding my searches for people on Eigg, the name of James Campbell, the Registrar, has cropped up time and time again. In other words, he has been begging for inclusion here! Although he is a Campbell, he is probably not directly related to ‘my’ Campbells.

The Campbells and MacKinnons of the Western Isles seem to be like the Jones in Wales, and the Smiths in England. In other words, having the same name, so-called isonymy, does not mean that one is directly blood-related. However, the MacKinnons of Eigg, Muck and Oban seem often to be related. Whatever, James was certainly an ‘important’ person on the island as can be seen by his dress in the photo included here.

I have accessed the photo from An Island and its People: Eigg a Photographic Record (2005: 4). This booklet points out that a studio photo of this type could cost more than a week’s wage. James and his wife Jessie are shown wearing their ‘Sunday best’. James even has a timepiece.

What is also of interest is that my great grandfather, Roderick Campbell, the Eigg ferryman, also paid to have such a studio photo. Obviously, Roderick was not a rich man; but he probably considered himself to be equally important as the ‘important’ men of the island, such as James Campbell. So, it was probably this vain streak in him that urged him to dig deep into his pockets to pay for such a studio photo.

An Island and its People: Eigg a Photographic Record also points out that James Campbell was also in charge of poor relief and thus a much feared person. Exactly why he was ‘feared’ is not explained; but anyone who has read the novels of Charles Dickens can understand why. The inadequacy of poor relief in the 1800s is also related to infanticide, which I will discuss later in this book.

MacGillivray Family Tree

As mentioned above, my cousin Iain MacGillivray gave me access to the family history of the MacGillivrays. He claims that not only are we related to the ‘heroic’ MacGillivrays of Culloden but also to David Livingston of ‘Africa fame’! But I don’t intend to research this at present (2024), as I’m sure this is not done in a trice. So the conclusion is I ‘believe’ family myths and claims until proven otherwise. But as mentioned, corroborating or rejecting various hypotheses is a time consuming process. But even if one were to reject a hypothesis – it is nevertheless of value in contributing colour to family history!

To be honest, 99% of history is just ‘made up’ to suit the ideas of a generation, especially with regard to national histories, Family histories are perhaps less guilty of this misdemeanour – but also have a tendency to glorify their pasts. Histories like statues are constantly being constructed only to be torn down by a later generation. Of late we have been witness to the tearing down of the statues of defenders of slavery, colonizers and imperial invaders that were glorified in the past, such as Robert E Lee, the commander of the Confederate States Army.

Comparative History

Moreover, I will use a comparative history approach. Anyone who writes about history uses a ‘comparative history approach’, although they often do this implicitly, while pretending to be ‘objective’. Of course, it is impossible to be thoroughly ‘objective’, as things in the past, perhaps inadvertently, are viewed wearing the ‘glasses of the present’. However, I will ignore this imagined objectivity and compare past events to present events.

Innovative Digressions

I’m not sure if AI or ChatGPT is capable of making irrelevant digressions. But when writing ‘sagas’ like this book, I would die of boredom if I didn’t allow myself to make absurd digressions! Thus, the more irrelevant the digression the better. However, I can’t go ‘completely off the rails’, so try to restrict digressions to typical news stories of 300 words, while trying to include a topic of ‘general interest’.

In conclusion, I propose that this is an innovative methodology, ‘historical scenario documentary fiction’, as it uses imaginative elements while keeping fairly close to historical sources. In addition, it makes explicit the fact that certain elements of the scenario are fictionalized. I should also add here that these fictionalized accounts are based on the efforts of many authors and contributors (who will be accredited). I have also used secondary sources in this endeavour.