After providing these descriptions of Dugald and Katie’s agricultural pursuits around the time of the WWII and later, I think it will be a good idea to pause the narrative. I will briefly discuss the occupations on Eigg, roughly during the last hundred and fifty years. I will partly base this brief description on “An Island and its People.”

The first thing you notice about reading about occupations of people on Eigg is the fact that most of the occupations were so-called agricultural; this is opposed to industrial occupations. I have also written a little bit about my father’s family history in Edinburgh. His family, stretching back 200 years or more (see Paul’s family tree), mainly worked in industry, or jobs associated with urban occupations. There were mill master, millwright, engineer, police lieutenant, store keeper, rubber worker, book folder, print compositor; there were clerk, retailer, dress maker, mantle maker, brass and iron moulder, engine keeper, coachman, glazier, dock porter, sail maker, weaver, jewel case maker, iron dresser, slater, clock maker, and picture framer.

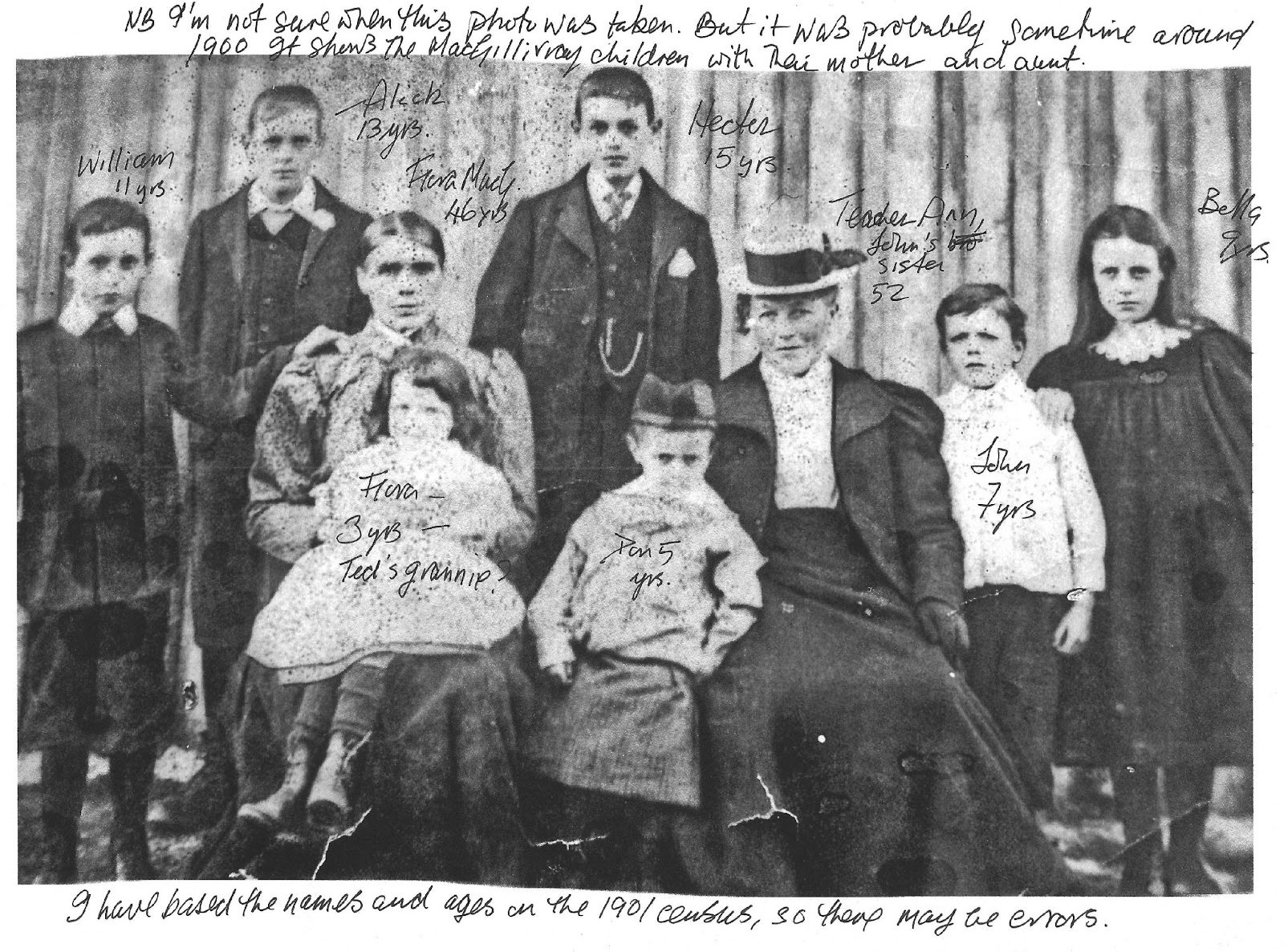

However, if you go further back towards 1800, some of the occupations were ‘agricultural’. There were farmer servant, ploughman, fisher, gamekeeper, and so on. Few of the above ‘industrial’ and urban occupations could be found on Eigg. However, there was also a shoemaker in Eigg, Donald Campbell (Domhnall Gobha) (Dressler, 2007: 108). In her book, Camille Dressler mentions the building of the new crofts at Cuagach, just around the end of the 19th century. She writes:

The building materials for the new cottages were ordered. The cottages would be far superior to the old ones. The roofs would be Ballachulish slates brought by the puffer boat to Laig Beach. 5 identical houses represented the height of modernity and an undeniable improvement in living conditions with their two upstairs bedrooms, parlour, kitchen and boxroom downstairs, wood panelling and cast-iron range! (Dressler 2007: 100)

I can’t remember if Camille wrote about who actually built these ‘state-of-the-art’ crofts. First of all, many of the building materials would have to be ‘imported’ from the mainland, such as the Ballachulish slates already mentioned. But building such crofts would also require skilled workers. As mentioned, regarding the occupations of my father’s extended family, there were masons, glaziers and slaters. It is doubtful Eigg had enough skilled workers to do all the jobs.

It seems Laird Thompson paid for the building of the crofts; so he most probably asked those people working for him to employ skilled craftsmen from the mainland. Of course, the men of Eigg would have helped build the crofts. The stones used to build the walls were most probably found on Eigg. And as mentioned above, Angus Campbell was employed as a joiner at Eigg.

Creative destruction: Joseph Schumpeter and Karl Marx

“Schumpeter characterized creative destruction as innovations in the manufacturing process that increase productivity. He described it as the ‘process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.’”

“In the earlier work of Marx (…) the idea of creative destruction or annihilation implies not only that capitalism destroys and reconfigures previous economic orders; but it also must continuously devalue existing wealth in order to clear the ground for the creation of new wealth; whether through war, dereliction, or regular and periodic economic crises.”

Of course, Schumpeter and Marx were not ideological ‘friends’:

“Marx personally desired socialism and believed it to be a superior economic system. But Schumpeter held the opposite view, believing in the power of private innovation and entrepreneurship and the benefits capitalism produced; ones he believed were far superior to the outcomes under socialism.”

In other words, Schumpeter holds the positive view that the destruction of old methods and the adoption of new methods will benefit ‘most people’ in the long run. However, in this context, one might cite John Maynard Keynes. He ironically noted, “In the long run we are all dead”; that is, the economists who talk about the ‘longer perspective’ and about how things will eventually perk up. This may be all very well, but what about the worker who loses his job today? Should he/she just wait around for this new bright future to emerge?

The reason for this slightly long digression is to point out that one cannot avoid economic changes; but one can discount economic theories, such as Schumpeter’s; it utilizes the idea of economic change to legitimize the benefits of a minority to the disadvantage of the majority. The examples here are many: the weaving machines that benefitted the factory owners to the disadvantage of the Luddite weavers. The

‘Wapping Dispute’ was a lengthy failed strike by print workers in London in 1986. The introduction of computer facilities that allowed journalists to input copy directly, rather than involving print union workers who used older “hot-metal” linotype printing methods. This was of great advantage to the Rupert Murdoch’s News International group, but obviously disadvantageous to the print union workers.

Of course, Rupert Murdoch has many ‘disciples’ with regard to looking after your own interests and disregarding the welfare of others. Who are the new disciples of Murdoch, Thatcher and Reagan? Elon Musk has said, I disagree with the idea of unions. Perhaps what he means is that he opposes the welfare of his workers if it leads to a reduction of corporate profits. I could mention many more so-called neoliberals here who disregard the welfare of the majority, but the list is too long!

The reason for this long digression is to point out that the destruction of old skills rarely benefitted the people of Eigg. First of all, in a small agricultural community, they were, on the whole, unable to adopt new methods, and create new jobs. Of course, as of 2024, new jobs have no doubt been created, such as within the so-called tourist industry.

Nevertheless, new industries on Eigg are only able to support around 100 people. In contrast, there had been 400 people some hundred or more years before. This calculation should also take into account the fact that the population of Britain has more or less doubled during the last 100 years; while the population of Eigg has been quartered, more or less, during the same period. Simply explained, this has involved the increasing transition towards an industrial society; where the agricultural sector was reduced in size, with regards to the demand for labour.

If one takes the Schumpeterian perspective, one might say that the 300 men, women and children who were removed from Rum (the neighbouring isle to Eigg) benefited in the long run. They managed to attain a higher standard of living in Canada than was possible in the Western Isles of Scotland. But, this was hardly the intention of Dr Lachlan MacLean who evicted the islanders of Rum, and replaced them with 8000 sheep. In fact, at the time, this resulted in a great tragedy. As told by a Rum shepherd, “the wild outcries of the men and the heart-breaking wails of the women and their children filled the air between the mountainous shore of the bay.”

To be sure, the laird of Rum, Dr Lachlan MacLean, was not the first or last laird in the Western isles of Scotland to disregard the welfare of the people under his responsibility. But, no doubt, the likes of Schellenberg and Maruma (‘recent’ lairds of Eigg); Elon Musk, Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and Rupert Murdoch (anti-unionists opposed to people’s welfare), and many others, can utilize the theories of neoliberalists, such as Schumpeter, to legitimize their selfish aims.

To sum up here, Camille Dressler points out that “Changes have been so rapid on Eigg as in the rest of the (islands and) Highlands; it is easy to forget what life was like only 50 years ago (An Island and its People, page 2).

Not least, Dressler refers to how the old methods of production, such as peat production were discontinued (page 1). She writes the following: “Ishbell MacQuarrie bringing down the peats laden in basket panniers on the horse’s back from the highland behind Laig Farm in 1914. The peat workings can still be seen, but they had ceased to be used by 1939. Behind her is a bare-footed boy leading a second horse. Children never wore shoes in the summer” (C. MacQuarrie Maclean 4).

Of interest here is the “bare-footed boy”. I think Dressler misses the point here. Without making further research, it seems obvious that this was related to poverty. My mother has never experienced dire poverty as far as I know. Obviously, when she lived in Glasgow as a child she wore shoes. But when she visited Eigg as a young girl, she would run barefoot across the ‘Singing Sands’ with the other children. I have worked as a kindergarten teacher for many years. I know that young children always prefer ‘less clothes’ rather than ‘more clothes’.

Undoubtedly, my mother had shoes when she was a child visiting Eigg, although she may not have always worn them. But the boy in the photo with Ishbell MacQuarrie would undoubtedly liked to have had a pair of shoes on the rough dirt roads of Eigg. In other words, the idea of ‘bare foot children’ is often a romanticisation of poor children’s hard working life.

Haymaking

The book, “An Island and its People” also refers to ‘haymaking’ which is discussed above. In other words, an old method of production that has been destroyed.

Return to a summary of “An Island and its People” – Crofting

I have mentioned above the various occupations on Kildonnan Farm. But, of course Eigg had many crofts. The official certificates found on ScotlandsPeople often state: occupation: ‘crofter’. But being a crofter involved being ‘multi-skilled’. First of all, the lairds would reduce the size of crofts for one reason or another; so it was impossible for a crofter to make a living from a croft (as described in Dressler (2007) regarding the croft of Dugald MacKinnon).

So apart from the multi skills of keeping a croft, such as grazing livestock, cultivating hay and oats, potatoes, cabbages, and cutting peat, crofters also had to participate in fishing. They also collected kelp in the early nineteenth century. One website reports that a crofter needed to carry out 200 days of work away from his croft in order to avoid destitution.

As long as the Isle of Eigg had agriculture as its main source of income, then it was a bygone conclusion that the island would become depopulated over time due to the process of advanced mechanization of agriculture and the demands of the market. So it is somewhat surprising that crofting was still a means of subsistence during the post-war period. Dressler (2007: 147) reports that Dugald was running three crofts during this period.

Dressler (2007) discusses in details the changes that came about. She mentionined the 1954 Taylor Commission among other things. She also mentions some of the problems were caused by the “present system of ownership” (p. 147). Dugald explains that government grants became available. “You got so much money per acre – it was about £7 per acre – that you put back into cultivation.” (Dressler, 2007: 148).

Modernization of the housing was also helped by government grants. Amongst the modernizing was water on tap, inside toilets and gas piping for lights and cookers (Ibid). However, there was a lack of diversity and other opportunities in the 1950s, such as tourism and fishing (Ibid).

“An Island and its People”( Isle of Eigg History Society: 2005: 5) shows the picture of my mother’s Auntie Flora peeling potatoes in her Cuagach cottage. I have described this elsewhere here, so I won’t comment on it further. I have also commented on the croft house at Bayview (p. 12), and the Kildonnan Farm garden (p. 13) elsewhere here, so I won’t add further comments.

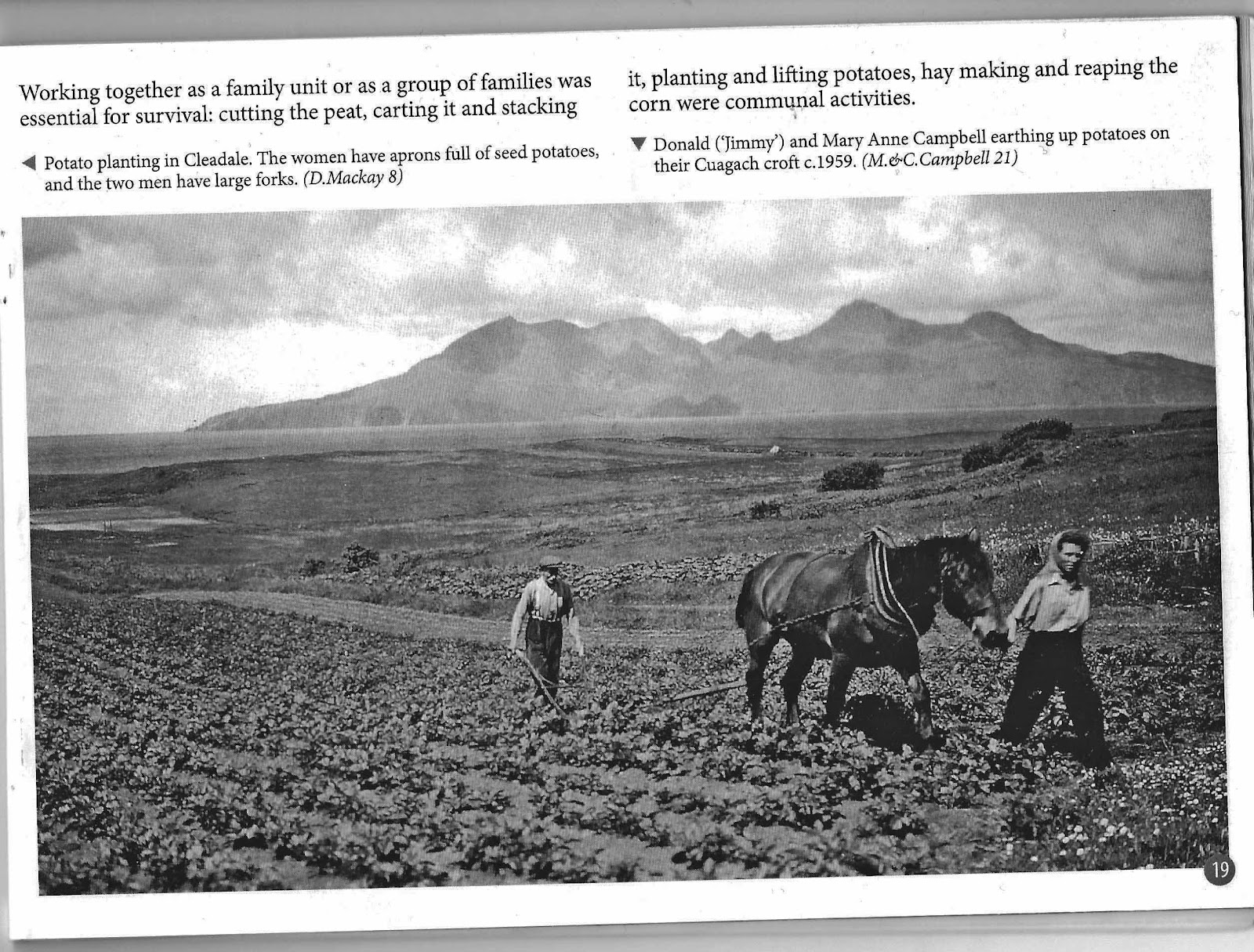

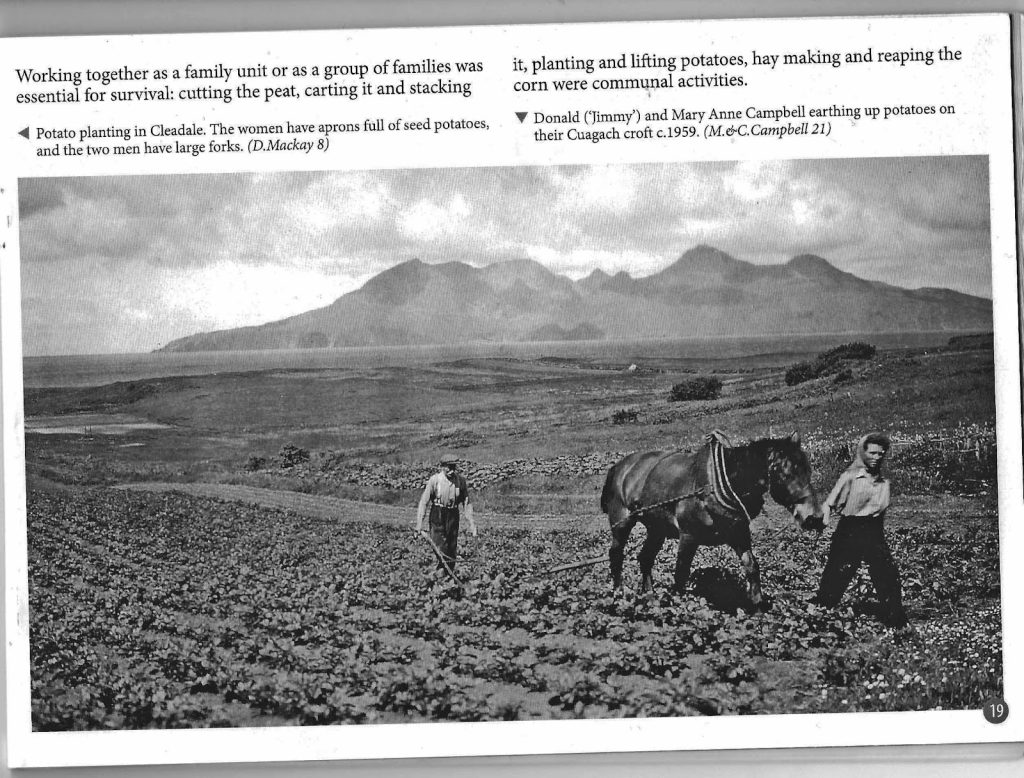

“Time-lag”: Ploughing with a horse in 1959!

Mary Anne Campbell and Donald ploughing the fields in 1959. I’m unsure of the family connection here. There is a time-lag between an innovative new tool or machine being introduced and its adoption in every area of an economy. Tractors had been introduced around 1890, and by the 1920s they had become the ‘norm’; yet, on Eigg, they were still using horses 40 years later. This was a case of ‘something gotta change’.