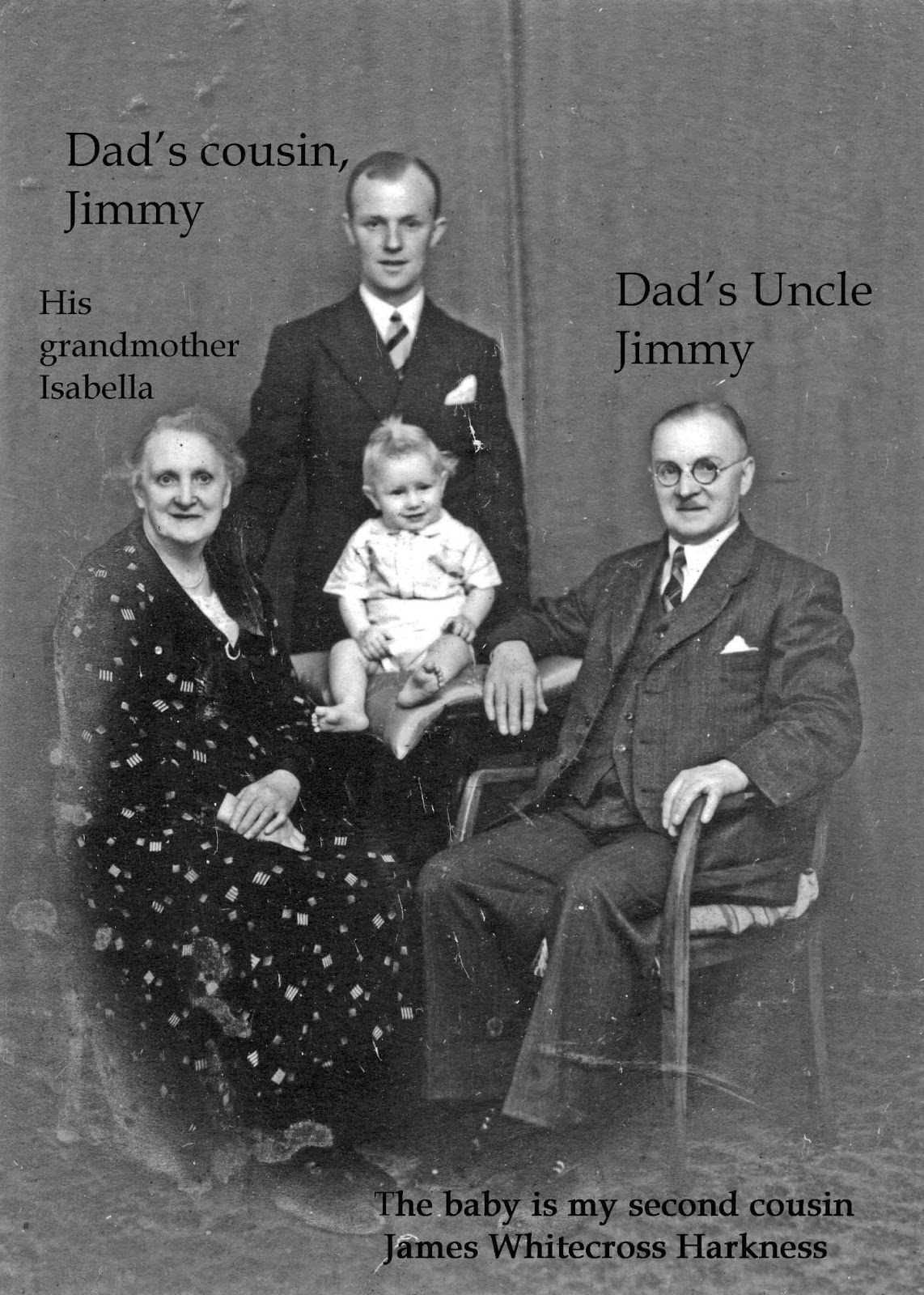

In 1945, my father was living at 2 Chesser Loan with his wife and three small children. Perhaps he thought this ‘family life’ boring. So perhaps he ‘deserted’ my mother to become one of the last defenders of the Empire (Burma), and enjoy the boons of colonial life. Perhaps like a John Flory, the main character of George Orwell’s book Burmese Days (1934).15 If so, he was not unlike many other men of his time; he was the breadwinner and the disciplinarian, but not a diaper changer!

Thus, considering my father’s virile character, his love of whisky, and the free availability of women in colonial Burma, it is not unlikely that I have a relation in Burma (Myanmar) that I don’t even know anything about!

“Mandalay” by Kipling (1892)

After having mentioned Orwell’s Burmese Days, it seems unfair not to mention Margaret Thatcher’s favourite ‘British Empire poet’, Rudyard Kipling, and his poem, “Mandalay” (1892):

By the old Moulmein Pagoda, lookin’ lazy at the sea,

There’s a Burma girl a-settin’, and I know she thinks o’ me;

For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple-bells they say:

“Come you back, you British soldier, come you back to Mandalay!”

Come you back to Mandalay,

Where the old Flotilla lay;

Can’t you ‘ear their paddles chunkin’ from Rangoon to Mandalay?On the road to Mandalay,

Where the flyin’-fishes play;

An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!‘Er petticoat was yaller an’ ‘er little cap was green;

An’ ‘er name was Supi-yaw-lat – jes’ the same as Theebaw’s Queen,

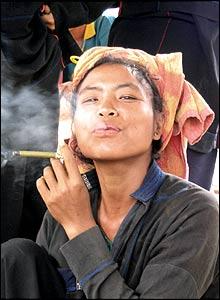

An’ I seed her first a-smokin’ of a whackin’ white cheroot;

An’ a-wastin’ Christian kisses

on an ‘eathen idol’s foot;Bloomin’ idol made o’ mud

Wot they called the Great Gawd Budd

Plucky lot she cared for idols when I kissed ‘er where she stud!On the road to Mandalay…

When the mist was on the rice-fields an’ the sun was droppin’ slow,

She’d git ‘er little banjo an’ she’d sing “Kulla-lo-lo!

With ‘er arm upon my shoulder an’ ‘er cheek agin my cheek

We useter watch the steamers an’ the hathis pilin’ teak.16

Elephints17 a-pilin’ teak

In the sludgy, squdgy creek,

Where the silence ‘ung that ‘eavy you was ‘arf afraid to speak!On the road to Mandalay;

But that’s all shove be’ind me – long ago an’ fur away

An’ there ain’t no ‘busses runnin’ from the Bank to Mandalay,

An’ I’m learnin’ ‘ere in London what the ten-year soldier tells:

“If you’ve ‘eard the East a-callin’, you won’t never ‘eed naught else.”

No! you won’t ‘eed nothin’ else

But them spicy garlic smells,18

An’ the sunshine an’ the palm-trees an’ the tinkly temple-bells;On the road to Mandalay;

I am sick o’ wastin’ leather on these gritty pavin’-stones,

An’ the blasted English drizzle wakes the fever in my bones;

Tho’ I walks with fifty ‘ousemaids outer Chelsea to the Strand,

An’ they talks a lot o’ lovin’, but wot do they understand?

Beefy face an’ grubby ‘and –

Law! wot do they understand?

I’ve a neater, sweeter maiden in a cleaner, greener land!On the road to Mandalay;

Ship me somewheres east of Suez, where the best is like the worst,

Where there aren’t no Ten Commandments an’ a man can raise a thirst;

For the temple-bells are callin’, an’ it’s there that I would be

By the old Moulmein Pagoda, looking lazy at the sea;On the road to Mandalay,

Where the old Flotilla lay,

With our sick beneath the awnings when we went to Mandalay!19O the road to Mandalay,

Where the flyin’-fishes play,

An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay !

Comment on “Mandalay”

Ironically, in the poem “Mandalay”, Kipling refers indirectly to the Suez Canal. The British appropriated the Sues Canal in the late 19th century, enabling them to consolidate their Empire. However, it was the Suez Crisis in 1956 which perhaps marked the watershed of the ‘dissolution of Empire’.

Defenders of the Empire

In other words, my father was one of the last of a line – a ‘defender of the Empire’. Ironically, during the Second World War, many British politicians, such as Churchill and others, talked about ‘defending the free world’. In reality, however, it was about ‘defending the Empire’; but this was a project that was doomed.

And yet, he was a willing defender, enabling him to support his family and pursue his career. This is in stark contrast to the Russian ‘Empire’ of today; as mentioned here, they use young Russian men as mere ‘cannon fodder’ in an attempt to ‘defend the Empire’. In fact, it seems the Russian army is ‘bankrupt’, so they have to rely on a privatised army composed mainly of criminals (the Wagner Group). But I will not pursue this topic further here. My point was to show a ‘historical parallel’, that is, ‘the end of Empire’.

Critic of the Empire

As perhaps mentioned elsewhere here, in my adult life, I became a professor of English. One of the poems I lectured on was Rudyard Kipling’s “Mandalay”, which is a ‘history in miniature’ of the British exploitation of Burma. In other words, Kipling managed in a few words to tell this history, which Orwell attempted to describe in many thousands of words (Burmese Days).

Of course, it was not Kipling’s intent to criticise the Empire; yet a close reading of his poem results in an implicit criticism of the Empire. I discuss the poem briefly below, but will also include my lecture notes (in abbreviated form) in the appendix. These notes can also be found on the website (http://artstraveling.com/).

Performance of the poem

The poem has been performed by many actors and artists. Among these is the actor Charles Dance in “The Crown” (TV Series 2016–2023), where the actor plays Lord Mountbatten.

Further Comment on ‘Mandalay’

Without going into great detail, the poem appears to predict American colonial invasions in the East that led to the emergence of ‘comfort women’ after the Vietnam War; for example, in Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines.

In other words, the ‘American Empire’ replaced the ‘British Empire’. The British exploitation of Asian women was replaced by the American exploitation of Asian women. I can’t go into details here, but there is obviously a difference between British imperialism and American global economic exploitation.

For example, the British Empire focused on exploiting resources (such as teak mentioned above), and governing the countries they exploited; whereas, the Americans focused on opening up new markets, without actually ‘occupying’ and governing countries that came under American influence. Of course, these differences are vague; the US behaved in much the same way as the British when they made the Philippines into a colony (but this was during an earlier historical period).

“Blue Angel” and Marlene Dietrich

Neither Orwell nor Kipling are able to capture the sexual life of soldiers in ‘war’ as in. thesame way that Marlene Dietrich could. She sang explicitly about ‘illicit’ wartime sexual relations, such as “Lili Marlene”, “Lola”, and other songs. These were in direct contrast to the songs of Vera Lynn that only hinted at the illicit sexual activities of soldiers overseas, such as in “Half as much – Isle of Innisfree – You Belong To Me.”

Going to the picture with your dad!

Ironically, in this context, I remember my mother saying to my father one Friday or Saturday evening when I was about ten years old; she said, “Take the boy to the pictures!” This was such a rare thing – that my father would spend time with me – which is why I remember it. We went to the pictures in Leigh, Lancashire, which was a few miles drive from the village of Culcheth where we lived between 1953-1963. Often you could choose between two films. I remember there was a choice between a cowboy film and the film “Blue Angel” starring Marlene Dietrich.

Soon, I understood that my father wanted to see the German film “Blue Angel”, although I wanted to see the American cowboy film. However, I acquiesced; so we ended up watching “Blue Angel” starring Marlene Dietrich. Absurdly, in retrospect, I discovered that this film was one of the first ‘talkies’ and was made in 1930; so this must have been some kind of ‘re-run’. But of course, as a ten year old, I was totally oblivious of all these details.

Of all the films I saw at the cinema in the 1950s, few are remembered. Yet, “Blue Angel” remains etched in my memory, especially, the hypnotic rendering of “Falling in Love Again”. Absurdly, the lyrics of her song seemed to fit in with my romantic aspirations of my young girl loves.

However, it seems likely my father had other ideas; he had probably engaged in ‘extra-marital’ sex when working in Burma; perhaps in the late 1950s this was where his mind was. He was ‘stuck’ in a conventional marriage with four sons, and had a ‘steady’ job; but like other men, his sexual imagination probably stretched to other scenarios. However, this was the 1950s, so his ‘dreams’ never materialised into extra-marital affairs on the domestic front. In other words, in the 1950s, sexual behaviour was socially controlled, and there were few divorces.

Absurdium

The fact that my father would desire the blonde Aryan ideal, Marlene Dietrich, has an aspect of the absurd. Of course, I’m pretty sure my father didn’t think of Marlene Dietrich as someone opposed to Nazi culture; she was just a ‘sexy German girl’. I will forgive my father in this instance, as the US promoted blonde Aryan goddesses such as Marilyn Monroe (the UK had Diana Dors!).

Whatever, although I was a young boy, the film “Blue Angel” made a lasting impression on my mind concerning ‘mysterious (forbidden) blonde women of German and foreign origin’.

“You belong to me”

Of course, this is a common theme of many songs and stories – when war separates men from their families. When writing about the Second World War, it is impossible to ignore the ‘poetess’ of the period, Vera Lynn. She sings a song that is focused on this theme – of men at war separated from their wives:

Half as Much / Isle of Innisfree / You Belong to Me by Vera Lynn

If you love me half as much as I love you

You wouldn’t worry me half as much as you do;

I know that I would never feel this blue

If you only loved me half as much as I love you;

I’ve met some folks who say that I’m a dreamer;

And I’ve no doubt there’s truth in what they say,

But sure a body’s bound to be a dreamer

When all the things he loves are far away.And precious things are dreams unto an exile.

They take him o’er the land across the sea —

Especially when it happens he’s an exile

From that dear lovely Isle of Inisfree.

See the pyramids around the Nile

Watch the sun rise

From the tropic isle

Just remember darling

All the while

You belong to me

See the market placeIn old Algiers

Send me photographs and souvenirs

Just remember

When a dream appears

You belong to me

And I’ll be so alone without you

Maybe you’ll be lonesome tooFly the ocean

In a silver plane

See the jungle

When it’s wet with rain

Just remember till

You’re home again

You belong to me.

Sources

15 Orwell, George. Burmese Days. 1934.

16 In the Rangoon photos in this book, one of the photos shows all the people my father worked together with. One of these was the ‘timber man’s wife’. In other words, the British exploited the resources of their colony, such as teak, a valuable tropical hardwood tree.

17 Elephants were used to transport the teak. When the elephants were too old for work, they were slaughtered for their meat and tusks (as also described in Orwell’s “Burmese Days”). Also mentioned in this book under “The Scottish colony”, my father had elephant tusks and a dinner gong which he had transported back from Burma.

18 In one of my father’s letters to my mother he mentions he doesn’t like the way the Burmese women smell; this was probably in reply to a question from my mother concerning the ‘allure’ of Burmese women; thus, his description of them ‘smelling’ was probably to allay her suspicions. But the ‘smell’ could very well have been “them spicy garlic smells”, not to mention the smoke from the cheroots they smoked (mentioned in the poem) which lingered around their bodies.

19 “With our sick beneath the awnings”: This refers to soldiers suffering from venereal disease. Kipling knew that a British soldier was actually more likely to die of disease (such as sexual disease) than in combat. Many of the British soldiers in Burma contracted sexual diseases. Of course, when Kipling wrote the poem (1890) venereal diseases were much more dangerous than they are today, and could be fatal. My mother, on her own admission, was quite naïve when she was a young woman, telling me on one occasion that she didn’t know what a lesbian was until her late twenties. So although she may have expressed concern about my father meeting Burmese women in her letters, she was probably unaware of the dangers of sexually transmitted diseases.

25 https://genius.com/Vera-lynn-half-as-much-isle-of-innisfree-you-belong-to-me-lyrics