When Morag was a small, young girl, she asked her grandmother, Mary:

“Grandma, why does nae mither nae bide with us, and how come ah hae na faither?”1 2

“Mah dear, ye wull hae tae ask yer mither that quaistion. She wull come ‘ere oan Sunday.”

Morag’s mother worked on Kildonnan Farm as a dairy maid, and she visited the McKay croft when she had some free time.

Sunday, finally arrived. Morag’s mother walked through the door.

“Whaur urr ye mah bonny wee darlin’?” was the first thing Mary, the mother, said when she walked into the croft cottage.

“A’m ‘ere mither!” Morag said excitedly in a high-pitched voice running into the arms of her mother.

“Dae ye miss yer mither? Come ‘n’ sit oan mah knee – ‘n’ gie yer mither a wee hug.”

“Grandmother said ah shuid ask ye whaur is ma faither? A’ mah friends have faithers. How come I dae nae ah hae a faither lik’ th’ ither girls. ‘N’ how come ye don’t bide th’gither wi’ us here mither?”3

“Mah dear. Yer mither has tae wirk, sae we hae food to eat.”

The mother was clearly touched by her daughter’s questions, but she tried to hide her feelings.

“’N’ yer faither. He cannae bide wi’ us, fur he bides somewhere else. Dear, dae nae ask tae many questions. Ah kin tell ye mair whin yer older. ‘N’ dae nae ask ither fowk, fur we dae nae waant fowk tae gossip.”4 Morag wasn’t happy with her mother’s answers, but just had to accept them.

As Morag grew older she started to hear rumours. And some of the mothers would not allow their children to play with her, saying, “Dinna play with that lassie – she is a bastard. She wull bring shame on us.”

At first, Morag didn’t even know what the word ‘bastard’ meant. She didn’t want to ask her mother or grandparents more questions. But she was a clever, young girl, so she eventually realised that it meant her parents were not married. She heard more rumours about how she was conceived – some saying it was the result of love – others saying the result of force. Other than her mother, with whom she has never truly talked about the subject anymore, and a father she only knows by his name, who will ever know, she thought?

She may be young, but her mind is mature enough to consider and wonder why the world solely blames her and her mother for their tragic fate, rather than the father she never met who started it all. If she’s born out of love, then why does her father never choose them? And if it’s by force, then why is there no justice served for her mother?

She may have never gone to school but she sure knows the names of things or what describes them — things that our eyes can see, and our skin can feel. Common words that she has encountered on a daily basis are words that sometimes flutter but mostly sting and pierce. Even the rudest and bluntest ones, for it has been tagged right next to her name, as if ‘shame’ rhymes with MacKinnon, and ‘bastard’ with Morag, for as long as she can remember. Who would not, when it bites and leaves marks not on her skin, but on her soul? She thought to herself.

How would she not know when people talk about her with no shame? As if talking about one’s life right under the heavens is a necessity they cannot do without. There’s no such thing as respect. The MacKays and their shamed granddaughter became something the local people would gossip and whisper about, a thing of entertainment. But really, what has she done, she thought to herself. She’s barely 13 —just a girl, and not yet a woman. There are a lot of questions running around inside Morag’s head, but one thing is certain. The world is undoubtedly not a nice place for someone like her and her mother.

She doesn’t always have her mother beside her or a friend to talk to, other than a pair of loving grandparents with whom she doesn’t want to cause any trouble. If there’s something she can really call happiness, it is those stolen moments by the burn,5 where she bathes alone, and washes clothes.

The Galmisdale Faerie of the Burn

She loves the sallying and sparkling of the water as it rushes over the ferns and washes over the pebbles, coming from up in the hills, and bickering down until it passes by their croft. She likes to think that when the child-like burn reaches the beach it will be swallowed and embraced by the mother sea, which will cleanse the water of the moss, twigs, and detritus it has picked up through its life on its way down the hillside. It is these little things that ignite a spur of joy and delight in her innocent heart.

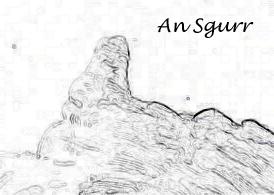

Who will judge her? The towering and mighty God-like rock, the An Sgurr, which towers over Galmisdale? That mighty, high, and erect rock would never judge her! Neither would the burn. The burn murmured under the moon and stars, but didn’t murmur her name in blame or shame, like the men and women of the Isle did. Men and women may come and go, but the burn will go on forever.

She giggled at her own silly, girlish thoughts. Those times were like bliss to the young Morag. The burn was a place she thought she could be devoid of shame for a time. But, the rest of the time, she who has never harmed a soul, received more hatred than her frail shoulders could bear. Why is that so? she thought to herself.

Sources

- I have to apologise to Scottish readers here. First of all, my great grandmother didn’t even speak English. But of course, I can’t report her speech in Gaelic! But to add insult to injury, I have decided to give the characters some kind of ‘Scottish English’ with the aim of being ‘authentic’. Of course, I am ill-equipped to this task as I am a Sassenach (born in England). However, my defence is that I have read “Oor Wullie” and “The Broons”, and had to listen to my Scottish parents for many decades. In addition, my younger brother Gavin – also an avid reader of “Oor Wullie”, “The Broons” and “Para Handy” also used to annoy his siblings and parents when he was a kid by attempting a Scottish English dialect in his daily speech.

Apart from these considerations, there are several websites that can translate into Scottish English, such as http://www.scotranslate.com/ However, I haven’t totally relied on this website, because hopefully this story might reach a wider audience – so I have removed some of the more inaccessible ‘Scottish’ words, such as ‘blether’ (talk), and ‘but n’ ben’ (cottage), and so on. Especially, as I remember my father used the word ‘blether’ to mean ‘talking nonsense’, not just ‘talking’, for example, “What are you bletherin about?” (That is, “What nonsense are you saying now?”). In those instances where the Scottish English seems unclear, I have given a standard English version in an endnote.

In retrospect, perhaps I shouldn’t ‘apologize’. Many of the words of Scottish English have their roots in Old Norse, such as ‘kirk’ (church) and bairn (child). I do not have knowledge of Scottish Gaelic – but just using common sense, it seems most probable that Scots Gaelic is influenced by Old Norse – this is at least evident from name places. In that I speak fluent Norwegian and can read Swedish and Danish, then perhaps I am highly qualified for this linguistic challenge – of creating ‘old ways of speaking’. ↩︎ - Grandma, why doesn’t mother live with us, and why do I have no father?” ↩︎

- Grandmother said I should ask you where is my father? All my friends fathers. Why do not I have a father like the other girls. And why don’t you live together with us her mother? ↩︎

- And your father. He cannot live with us, because he lives somewhere else. Dear, do not ask too many questions. I can tell you more when you are older. And do not ask other people, because we do not want people to gossip. ↩︎

- ‘Burn’ is Scottish for stream or brook. ↩︎