Morag goes to Glasgow is a short story written by Rory McJoy about the daughter of Ruaridh and her namesake, Morag. She was to be sent off by him so she could spread her wings.

“Splash! Whoosh!”

The sea alternately hits the boat’s starboard and port as the small ferry-boat fights the waves to row towards the ship that will take Roderick’s daughter Morag to the mainland.

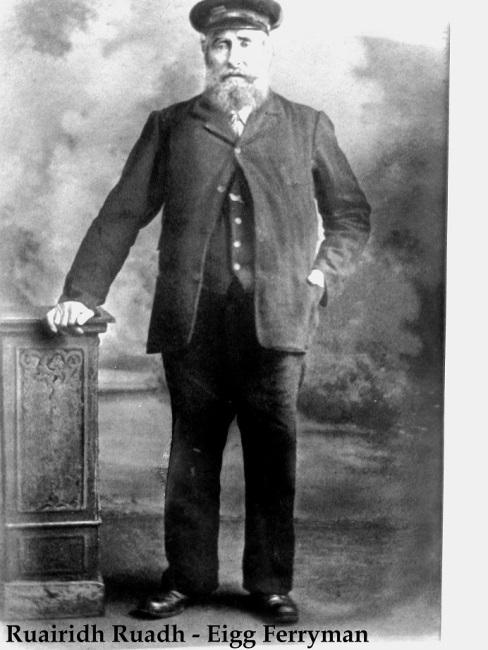

The boat almost keels over when a giant wave hits it. Roderick, being a seasoned ferryman, pulls strongly at the oars. His mate, Alasdair MacKinnon, adjusted the rudder of the boat. No harsh wind or fierce sea can defeat Roderick and Alasdair. Roderick had experienced the pain of losing five of his ten children. He had also suffered the pain of losing his beloved wife, Sarah (aka Morag). He is a man of indomitable spirit, as strong and unconquerable as An Sgùrr.

This trip is a special one, and only one passenger is on board, Morag, named after his wife. Roderick is not sure whether he is happy or sad about this trip. He knows that he will not be able to see his daughter for a long time, yet he wants her to spread her wings. She is so like him in spirit that he has no will to stop her from leaving the island of Eigg.

The year is 1910. Morag yearns to live a life that is different from what she has known all her life. Morag can hear the soft susurration of the sea, and the strong gusts of the wild offshore wind. The wind whips Morag’s hair, tousling it in wild abandon. Each gust creates a disarray that mirrors the movement of the churning waves below. Morag is grateful for such a mess because it disguises the tears falling down her cheeks. She looks at the fast-disappearing silhouette of Eigg Island, her home for about eighteen years of her life. She doesn’t want to leave home, but it has nothing more to offer her.

Already eighteen, she has received a school leaving certificate. She is a Gaelic speaker, like everyone else on Eigg. But the authorities insisted that the ‘primitive’ Gaelic people should forget their own language, and learn the language of their English ‘masters’. Thus, the children of Eigg had to forget the language of their parents and forefathers, and learn English at school.

Morag excelled at the small school on Eigg, which only had about 40 pupils. She did well in all the school subjects, and came top in the English language. However, English was of no use on the little island of Eigg, where everyone spoke Gaelic. She is an intelligent girl. She knows that the big city of Glasgow has so much in store for her.

Morag craves adventure, as do most young people her age. She has heard wonderful stories about the city, and how it helps to make people’s dreams come true. The sea and the waves help her on her way. They become instigators, whispering to her about distant places and unseen horizons. “Oh, whit fun ye are gaun’ae have in Glasgow,” they purr in her ear with glee.

Roderick finally manages to row his boat alongside the ship that’s on its way to the mainland. They hug each other for one last time. “May the wind o fortune be wi ye aye.” He whispers in her ear before turning his back, as she climbs aboard the ship. Once on deck, she waves goodbye to her father, tears in her eyes. The ship gradually steams towards the coast, creating a distance between them.

Morag looks at the approaching shores of Mallaig, the terminus of her sea journey. Disembarking from the ferry, she is still thinking about her father, and her brothers, sisters, friends and relations on Eigg.

With misty eyes, Morag looks around Mallaig and its busy port. Knowing there is no turning back, she wipes her tears away and searches for the train station: the West Highland line. It is her first time to see a steam locomotive – she feels lost for a moment. Gathering her wits, she buys a ticket to Glasgow, with the money her father had given her.

She boarded the train to Glasgow. Sitting alone, she gazes out the window and marvels at the beauty of the Scottish landscape. She feels a frisson of excitement when the train passes over the Glenfinnan Viaduct. Its construction began in 1897 and was finished in 1901. She had heard of its majesty from the islanders who had also travelled across it, on their way to Glasgow.

The Glenfinnan Viaduct does not disappoint her. With its twenty-one arches, it is a sight to behold. In fact, it is the highlight of her long train ride from Mallaig to Glasgow, with a stopover at Fort William and other towns and villages, the names of which she can’t remember. She has travelled for 164 miles from Mallaig to Glasgow in what seems like half a day’s journey.

Before she travelled to Glasgow, some of her friends on Eigg had given her an address in Glasgow, where she could find accommodation. It was in the Plantation area of Glasgow. Her roommates there were also of about the same age as her, also coming from the Small Isles, especially Eigg and Muck.

Her friends on Eigg had also told her where she could find a job in Glasgow – in a nursing home, caring for the elderly. She worked at this job for a number of years, but she felt listless, as it is not in her nature to take care of other human beings. She is a child of the land, and it is in her nature to nurture living things sprouting from the soil. With farming being done exclusively by men, she continues to be a nurse to support herself. Her niece, Morag McKinnon, would also later work as a nurse in Glasgow, and stay with them in their tenement flat.

But then, in 1914, the First World War broke out. This was four years after she had travelled to Glasgow in search of work and a new life. Morag, like many others, celebrated the start of the war, which may seem unthinkable to people today. People in Glasgow celebrated, just like in the capital of Britain, London, shown here are the celebratory pictures outside Buckingham Palace.

Of course, little did Morag know about what the future would bring, not least the deaths of many in her extended family, including Alexander MacGillivray, the piper, and brother of her future husband, Hector.

World War One was nothing to celebrate about, in retrospect – with the death of millions! Nevertheless, it offered opportunities for women such as Morag. When men left to go to war, there was no one left to till the land, operate the machines in the factories, or drive the city’s trams.

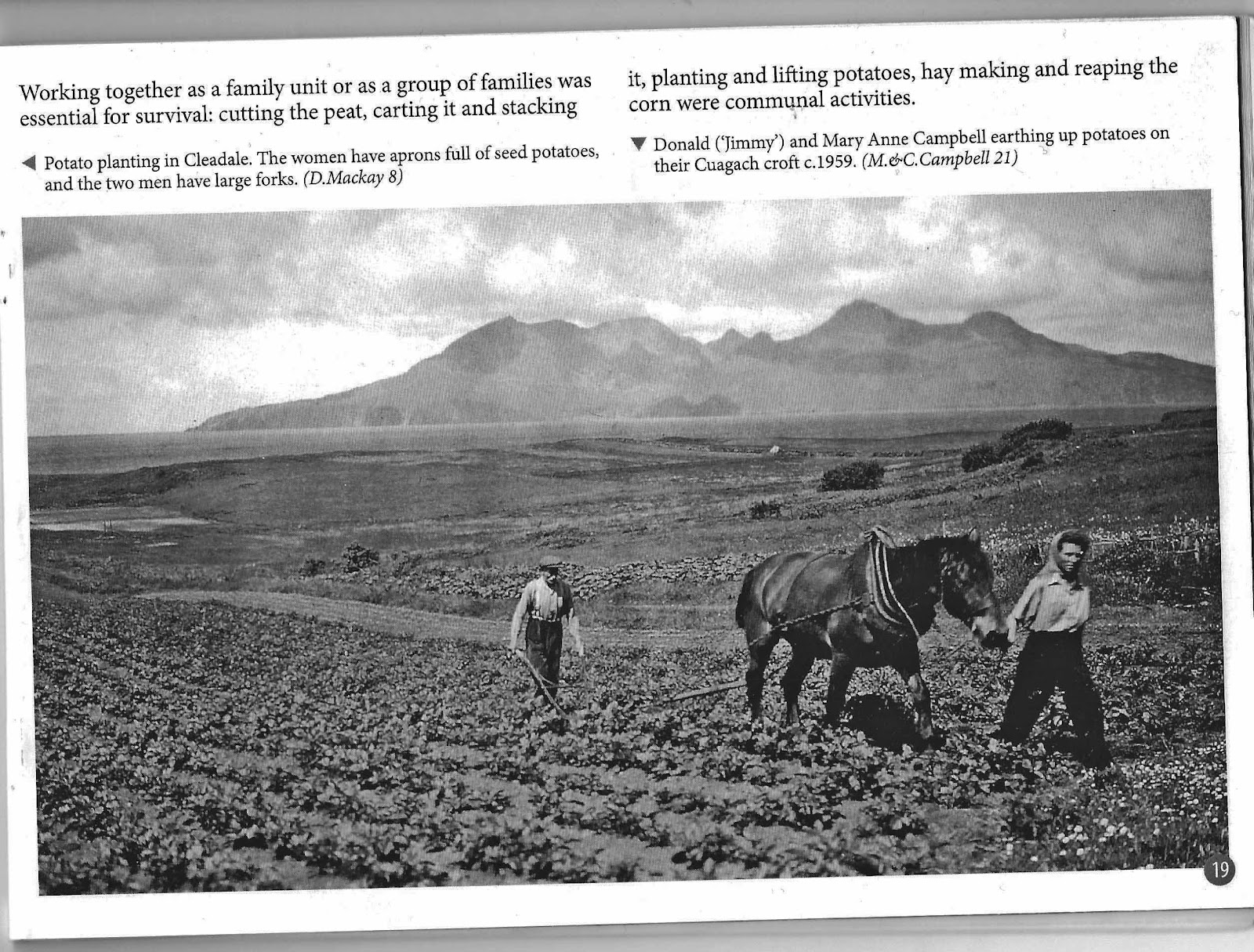

Women were considered to be too ‘weak’ to do the jobs of men, plough the fields, operate machines, and drive trams. However, the war, of necessity, changed the mindsets of men. With the dire shortage of male labour, women were given ‘men’s jobs’. One such job was that of being a ‘land girl’.

Morag became a ‘land girl’, gladly giving up the ‘feminine’ profession of being a nurse, which had never really suited her. This was highly ironic – being a ‘land girl’, or farm girl, was something Morag had done since her early teens on Eigg. At five foot ten she was taller than most of the men on Eigg.

Her father Roderick was renowned for his strength on the island. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree, they say. Morag was a very handsome woman, but also as strong as an ox, so God help any boy that teased her, she would floor him in an instant. So no boy would ever challenge her, so as to avoid the humiliation of being beaten up by a ‘girl’. So farm work came easy to her, whether this was standing behind a plough, or loading up a boat with heavy timber. As said, she was a ‘farm girl’ through and through.

But being a ‘land girl’ is not an easy undertaking. Some skeptics, most of them men, scoff at them with a knowing gleam in their eyes. They are quite sure that the women will not be able to bear the demands of the job. Surely, some of the women gave up after a while. But not Morag. No sir! You can take a woman away from the farm, but you can’t take the farm away from a woman who has lived on the farm all her life.

Farm work is easy for Morag, as her father, aside from being a ferryman, is also a crofter. She and her siblings assisted their father, Roderick, from time to time in managing their croft. Her brother-in-law, John MacKinnon, would also later become manager (grieve) of Kildonnan Farm, and she would help him in his work when she returned to Eigg on visits.

Besides, Morag thinks being a ‘land girl’ plays a pivotal role in food production, especially in times of war. It awakens in her a sense of patriotism, which nursing (her previous profession) never did.

She ignores the critics and the naysayers, donning garments befitting a farmer, clothes that allow ease of movement, including trousers and strong boots. It is practicality over fashion and the preconceived notion that only men can wear trousers. Comfortable and practical, trousers worn by women usher in a turning point in history.

Armed with confidence brought about by wearing trousers, Morag and the other ‘land girls’ become more ‘empowered’, and take to smoking cigarettes and even swearing. Morag becomes friends with a woman fondly called Podger, the first woman she knows who swears quite a lot. Perhaps it is because of the stress of their job that the ‘land girls’ resort to smoking cigarettes and even swearing. Or maybe it is the confidence brought about by wearing trousers.

Perhaps a new age has come—an era of empowered women who don’t care what other people (especially men) might think. It can be all of the above reasons. Or none of them. And who cares?

So here begins Morag’s adventures in Glasgow: from being a nurse to becoming a “land girl.’ What will her next adventure be?