I would say that I have a good memory. But what is memory, really? How do we remember things? Our memories actually trick us into believing that we remember the original event and that we retrieve the original memory. But in reality, each time we retrieve a memory, the memory is potentially changed; thus, you retrieve the memory you stored after the last retrieval rather than the original memory.7 It’s not so much ‘memories’ but memories of memories of memories.

We also tend to forget the importance of our senses in relation to remembering: visual, tactile, smell, taste and hearing, as well as our interaction with the environment. Our memories ‘remember’ images, but it is how we intellectualise the information that we gather through all our senses.

Of course, ‘seeing’ is one of our strongest senses. But just like how dogs sense us more through smell, we humans can also recognize a special smell or aroma after the passage of a long period of time. A personal example is how the smell of custard or mashed potatoes can bring back old memories of school dinners. In this way, the sense of smell can often be related to ‘original’ memories that have not been intellectualised or changed.

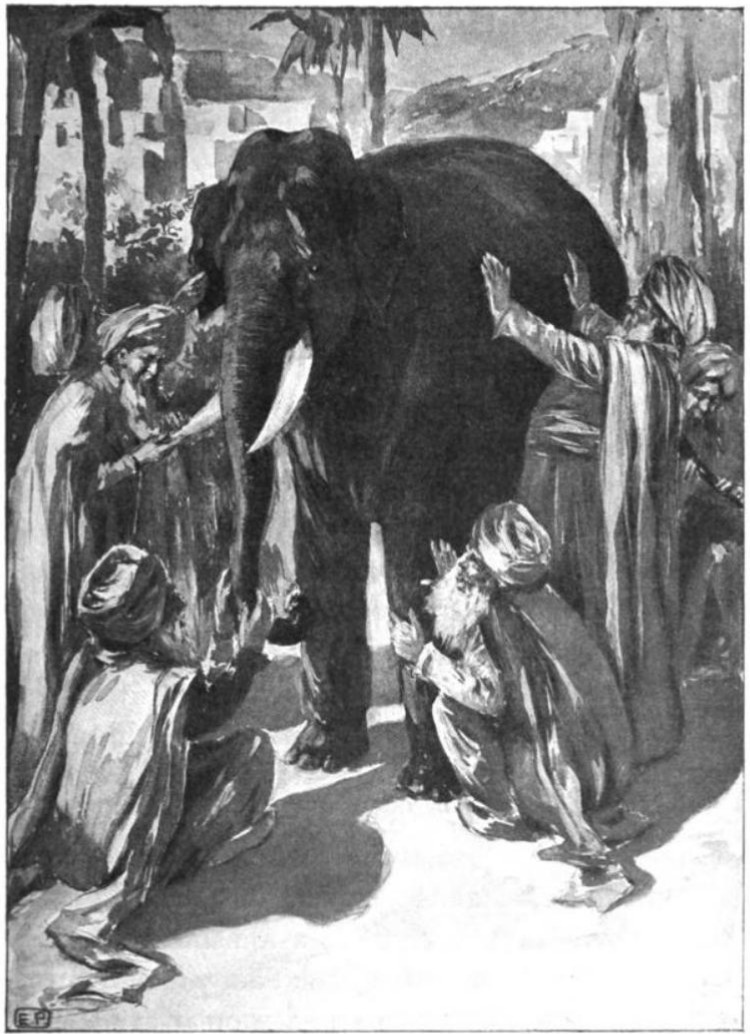

Of course, not least, perspectives are always subjective. My younger brother Gavin, who is nine years younger than me, seems to always remember an event so differently from me that it is almost like it is two different events. In this context, the parable of the “Blind men and an elephant” springs to mind.8

7Joseph E. LeDoux: Reconsolidation theory.

8https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/7569676-conceptual-differences-between-consolidation-and-reconsolidation-according-to-consolidation-theory 28 Dec. 2021.