This post will be describing the several key wedding places that will be mentioned on the post Wedding Festivities. Some of them had media appearances, while some may have been closed already as the decades passed by.

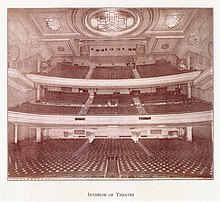

Glasgow Empire Theatre

“In 1897, on the site of the Gaiety Theatre at 31–35 Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow Empire Theatre opened. It was one of the major and leading theatres in the UK chain of theatres owned and developed by Moss Empires. The Empire presented a variety of revues, musicals, and dances such as Pavlova, winter circus, pantomimes, and ice performances. Over the years, many stars have appeared, including the likes of Lilly Langtry, Laurel and Hardy, Sir Harry Lauder, G. H. Elliott, Tommy Lorne, Evelyn Laye, Will Fyffe, Harry Gordon, Robert Wilson, the Logan family, and Andy Stewart. Top-tier American performers, such as the Andrews Sisters and Billy Eckstine, were also warmly received. Fats Waller made his European debut at the Empire in 1938. (…)”25

George Hotel

Like the Empire Theatre, the George Hotel26 is no longer in operation – much like everything else in Glasgow from the 1940s it seems. They stayed in room 78 (perhaps 18 – the writing is unclear). The room cost nineteen shillings (about £1). This would probably cost £300 today – but then £1 was obviously worth more in 1940.

Trainspotting

While doing a search on the Internet for George Hotel, I came across one or two websites referring to the novel and film “Trainspotting”. I initially dismissed it as irrelevant to our discussion, but in retrospect, I believe it may be relevant after all. First and foremost, the film provides images of the hotel27 through some of its key scenes. A memorable example is the one filmed in the circular hotel room where the drug deal took place. Second, the novel contains excellent examples of Scottish vernacular. Unfortunately, I am still unable to replicate it authentically in my account despite using ‘Scotranslate’.28

Interestingly, in the film and novel’s world, the characters were actually in London. In other words, both the characters and the author are not from Glasgow, but from Edinburgh. Coincidentally, this city was also where my father was born. Thus, the broad Scottish vernacular of the characters in the novel and film is based on the Leith vernacular of Edinburgh. My father’s Uncle Jimmy (James Whitecross Harkness) lived in Leith. It was just 2-3 miles away from where my father lived.

Any large city will have diverse accents. I have mentioned before that the Edinburgh accent is more “educated” than the Glaswegian accent. Of course, this is a generalization; many people in Edinburgh also have “broad” Scottish accents as depicted in the novel and film.

In retrospect, this may explain why my father’s language was full of expletives and colourful expressions rather than being ‘educated’. His dialect, however, was not opaque (non-understandable) to those unfamiliar with the Scottish vernacular. This is not the case with some of the vernacular in “Trainspotting”, such as:

“The Fit ay Leith Walk s really likes, mobbed oot man. It’s too hot for a fair-skinned punter, likesay, ken? Some cats thrive in the heat, but the likes ay me, ken, we jist cannae handle it. Too serve a gig man” (Welsh, 119).

I won’t attempt to ‘translate’ this. But the gist of it is that fair-skinned people (in Leith) do not like hot weather. This extract is quite amusing in several ways; it combines Scottish English words, such as ‘ken’ (you know), ‘cannae’ (cannot), with hippie/punk/black American slang of the twentieth century, such as ‘man’, ‘cats’, and ‘gig’. Moreover, ‘ken’ derives from the Norse. In modern Norwegian ‘kjenne’ means ‘know’. More specifically, it derives from the Germanic language.29

Irvine Welsh, the author of “Trainspotting”, when writing the novel, would obviously not have to use Scotranslate; he was already born in Leith. Thus, he was fully cognizant with the dialect. More specifically, he was able to transcribe it into the written word and use it as a tool to develop character.

25 https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Glasgow_Empire_Theatre Read: 3 August 2022.

26 “Situated at the top of the city’s Buchanan Street, the George Hotel kept its doors open for 162 years of business, offering accommodation to actors, performers, the rich and not so famous. Stan Laurel stayed here when he performed at the city’s Britannia Panopticon Theatre, just before he left for America, as did Cary Grant (then just Archie Leach) and later Joan Crawford. The hotel was known as the “nearest”, for it was handily situated between the main points of entry into the city, and ideally placed for all of Glasgow’s theaters. At one time it had over a 100 staff, including twenty-two chefs in its kitchens. http://www.myfriendshouse.co.uk/lost-glasgow/

27 https://dangerousminds.net/comments/michael_prince_photos_george_hotel

28 https://www.scotsman.com/arts-and-culture/scottish-words-week-edinburgh-dialect-1558426

29 “If something is beyond your ken, it is beyond your knowledge or understanding. The word ken only really appears in this phrase, but in some dialects of English in northern England, and in Scots and Scottish English, ken is more commonly used.

Ken in English means to know, perceive, understand; knowledge, perception or sight. It comes from the Middle English kennen (to make known, tell, teach, proclaim, annouce, reveal), from the Old English cennan (to make known, declare, acknowledge), from cunnan (to become acquainted with, to know), from the Proto-West Germanic *kannijan (to know, to be aware of), from the Proto-Germanic *kannijaną (to make known), from *kunnaną (to be able), from the Proto-Indo-European *ǵn̥néh₃ti (to know, recognize) from *ǵneh₃- (to know).”