Foreword

I’ve spent the last five years in writerly limbo. Now, with most stories drafted, I’ve applied for a sabbatical and am determined to finish my last few pieces so I can return to the east. One final story remains—about the Golden Flash, my teenage motorbike.

About five years ago (around 2020), I returned from an extravagant six-month jaunt through the East—cost me about $50,000. Let’s face it, peanuts for a Trump or Elon Musk, but a mortgage-sized hole in my modest Norwegian budget (I’m a Professor of English, pulling in roughly $90,000 a year).

If that weren’t enough, the COVID-19 pandemic hit right as I touched down. Broke and grounded, I found myself stranded back home. So, I dove headlong into a marathon writing spree—chronicling travel tales (censored), family drama, Roald Dahl-inspired memoirs, short stories… you name it. I even quit teaching, though I stayed on as a translator and editor at the university.

So just a few more, and I’m off on sabbatical, suitcase in hand and conscience clear, free to return to the East.

Golden Flash

Every tale has its long and short version.

The beautiful thing about many blues lyrics is that they often summarise a whole life into two or three lines, such as Cab Calloway’s “Down Hearted Blues”:

“I ain’t never loved but three women in all my life,

That was my mother, my sister, and the gal that wrecked my life.”

I’ll try and keep this one short. Well… that’s the plan, anyway.

Introduction

Mothers are excellent at one thing: warnings.

- “Walk on the pavement—don’t dash in front of traffic!”

- “Brush your teeth—or they’ll rot!”

- “Don’t play with bulls—they’ll gore you!”

But as you age, some of these cautions begin to seem oddly personal:

- “Cut your hair—you look like a girl!”

- “Don’t wear blue suede shoes with holes in them!”

- “Absolutely no motorbikes!”

- “And for heaven’s sake, no big Jaguars parked outside—people will think we’ve lost our class!”

My Glaswegian, working-class mother was determined we should join the lower-middle-class English ranks—though she always claimed to hate the English (along with everyone else, come to think of it). Her mantra? “Scotland first—may the devil take the hindmost.”

But rank and file in 1960s England meant modest cars: Austin 1100s, Ford Anglias—something unremarkable and unthreatening. A roaring 200 BHP Jaguar Mk VII? That would swallow an Anglia for breakfast—and ruin the “tone” of the neighbourhood. No thanks!

Now, I’m edging off topic again. The gist? Mum banned me from long hair, blue suede shoes, motorbikes, and luxury Jaguar saloons. Her dream was for me to join the RAF as a fighter pilot—defending the Empire. The problem? She didn’t know a thing about the British Empire, or about all the imperial acts carried out by the British Government.

For example, the Suez War of 1956 (some ten years before) was a catastrophe for Britain because it exposed the loss of British global influence—it was forced into a humiliating military withdrawal under intense pressure from the United States and the UN, triggering economic turmoil, political scandal, and marking the definitive end of Britain’s status as a first-tier world power.

So here it is: a brief sketch of a mother who feared bikes as much as blue suède shoes and empire ambitions she didn’t quite understand—setting the stage for my adventures astride the Golden Flash. Ready or not, the real story starts now.

Buying a Golden Flash

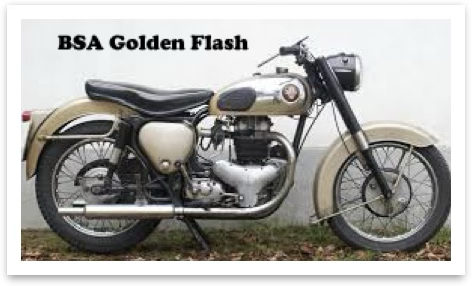

Despite my mother’s best efforts—and her occasional success in breaking me of reckless impulses (I once had to hand back a BSA Bantam bought for £5 and a white Mk VII Jaguar that I acquired via a lucky poker game streak)—she couldn’t stop me from acquiring a BSA 650 cc Golden Flash.

Forbidden Sport Bikes — My Early Years

This tale actually goes way back. When I was just eleven, Mum forbade me from riding anything with drop handlebars—too “dangerous,” she declared. So, instead of a lightweight racer, I got a heavy straight-handlebar bike. It was so cumbersome that I couldn’t keep pace with my friends, and eventually, my parents sold it for half the price.

In its place, I found a nearly free lightweight bike, which I painted yellow and black. That one—ah, that one I could actually ride, racing around with friends until the sun dropped. But enough about that… let’s get back to the Golden Flash.

Gavin’s Winter Blues

My brother Gavin—who was about nine at the time—sent me this memory:

“I remember one winter morning when it was freezing cold. You and I left at the same time for school. It took forever and a dozen kicks to start the bike. You wore just a grey pinstripe suit—no gloves, no coat—by the time you rolled out of the driveway your hands and face were purple! And in the evening, you came back totally blue!”

Classic teenage stupidity—no helmet, no goggles, no protective gear, and the seat wasn’t even screwed down. I must have terrified my brother Stuart and my friend Kevin Doyland (who later became Sergeant Doyland of Wickford police). They sat on the back once—and that was enough. I blasted off and the seat shifted back nearly a foot. Kevin thought he was falling off—understandably, he never repeated the experience!

Golden Flash vs. Jaguars and Triumphs

The Golden Flash wasn’t just flashy—it could out-accelerate an E-type Jaguar up to 50 mph, thanks to its low-geared gearbox from its “combination” (sidecar) build. Kevin’s solo 650 Triumph didn’t stand a chance. First gear on the Golden Flash… zero to 20 mph in the blink of an eye.

Try “once bitten, twice shy”—it applied perfectly in this case – most of my friends never wanted to sit pillion a second time, after experiencing G-force acceleration, sliding seat, and the burbling flames that were emitted from the twin exhausts nipping at their jeans!

Smart Sidecar Strategy

Some might wonder, “Why go for a heavy combination bike?” Simple: no licence required. Solo bikes over 250 cc mandated a licence, but combination bikes didn’t. Insurance was cheap too—because these bikes were usually driven by responsible family men, not thrill-seekers with death wishes.

Yet, among us less sensible youths, the Golden Flash offered a recklessly fun loophole. My friend Mick, for instance, lost a leg on a similarly powerful bike—but he used his insurance payout to buy a house that soon became the epicentre of wild parties in Billericay, Essex. Karma has a dark sense of humour, doesn’t it?

So there you have it: a mother’s misguided warnings, a teenager’s stubborn rebellion, a sidecar loophole, and a bike that could outpace a Jaguar. That’s the story of my Golden Flash—part youthful folly, part reckless triumph, all unforgettable.

Mick – the “Gatsby” of Billericay

Mick was known as the “Gatsby” of Billericay—except instead of, like Gatsby, trying to get his hands into Daisy’s panties at opulent parties, he hosted legendary “Wang Dang Doodle” get-togethers with teenage girls lining up by the dozen. If you were a teen boy who hadn’t yet “scored,” it was only because you’d never braved one of Mick’s parties. Every weekend, he sported a new girlfriend—apparently the ladies were drawn both to his charisma and the curiosity factor of his missing leg.

Mick tolerated whatever craziness unfolded—peel-outs, even a game of human pinball—as long as he married a fresh “bride” every Saturday night. That is… until one ill-fated party when guests “screwed off” every door in the house. But that’s another tale—I digress!

Riding the Bike

The Golden Flash was, unsurprisingly, a handful. I held the gearbox in place with my foot (it was never bolted properly), and the battery barely stayed put. The pièce de résistance? Two roaring exhaust pipes that housed dramatic flame-thrower routines just inches from your knees five minutes in. £11 never felt so hot (literally).

How I Got It

I spotted it rusting forlornly in a garden near Gavin’s school. The owner wanted £11. I paid up … and then had to push it home for a mile. Brutal—but worth it.

Dad, who owned a similar bike in the 1930s (before his uncle and cousins disowned him for irresponsibly buying the bike with the inheritance money after his mother’s death), fixed it in a snap—just a quick magneto brush adjustment. As soon as he flipped the kick start, the beast roared so loud I nearly fell over from fright.

Tea Tray in the Air

Testing it in the driveway, Dad appeared with a tray of tea and biscuits. I panicked, reached for the brake—and mashed the throttle instead. Dad sailed backward, the tray flew, and I was left mortified. One minute I was the hero; the next I was pretending gravity was playing tricks.

Sidecar Take-Off

Not long after, I removed the combination attachment, which was just a toolbox bolted to the frame—and tested it on Mountnessing Road. Top speed, no licence, and presume no parachute. I returned to a fuming Dad, who smacked me across the head. At 16, I’d learned to pack a punch, but couldn’t swing while gripping that heavy bike. Smart move, Dad—smart move.

Rockers in Billericay

My Golden Flash kicked off a local biker trend. My mate John Barker soon owned a Flash with cowhorn handlebars, looking every bit like a wannabe Hell’s Angel. He later sold it to my brother, Alistair, another story for another day.

One night, John rode that bike home with Big Bertha—after she’d “serviced” all the Billericay rockers at my house party. That bike became our key to the era’s underworld. Scary and thrilling. But this is another story, which I have written about elsewhere.

Biking to London

I often blasted to London to visit brother Stuart and wife Cath in their bedsit. No helmet, no goggles, flat-out throttle—86 mph, the max for the Flash’s low-geared setup. It was exhilarating … until a rogue bee in my eye nearly sent me face-first into the Thames.

Final Farewell

I eventually sold the Golden Flash for roughly the same £11 I’d paid—heading into inflation’s rearview. Today, a well-restored model fetches about £4,000 (that’s nearly a 400-fold increase!). Considering £10 in 1970 is now worth roughly £200—well, the bike’s value has truly “flashed” ahead.

I have many stories about the “Golden Flash”, but can’t include them all, but I should at least include one more:

Golden Flash and the Great Sidecar Incident

As mentioned, at the age of 16, I bought a BSA 650cc Golden Flash motorbike for £11. It had been rusting in someone’s garden for ages. Dad, who’d had something similar in the 1930s, fixed the magneto in 15 minutes. The roar it made when we first started it up nearly made me fall over with fright.

The bike came with a sidecar—or rather, a toolbox that pretended to be a sidecar. I eventually replaced it with a real one, but my mechanical approach was laissez-faire at best. On its maiden voyage, I let young Gavin ride in it. We hit the old humpty bridge over the River Wid, went airborne, and nearly watched the sidecar detach mid-flight. Gavin’s only complaint was that we didn’t do it again.

That was the Golden Flash: wild, reckless, loud—and unforgettable!