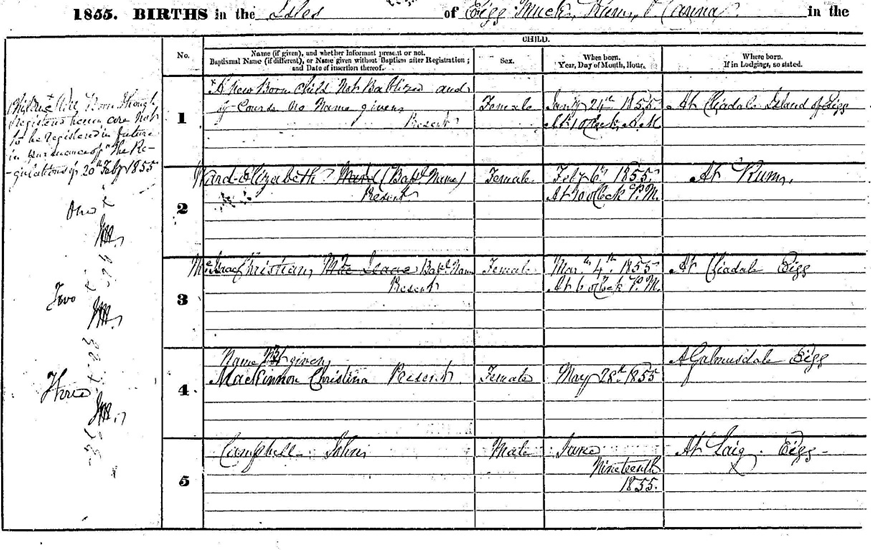

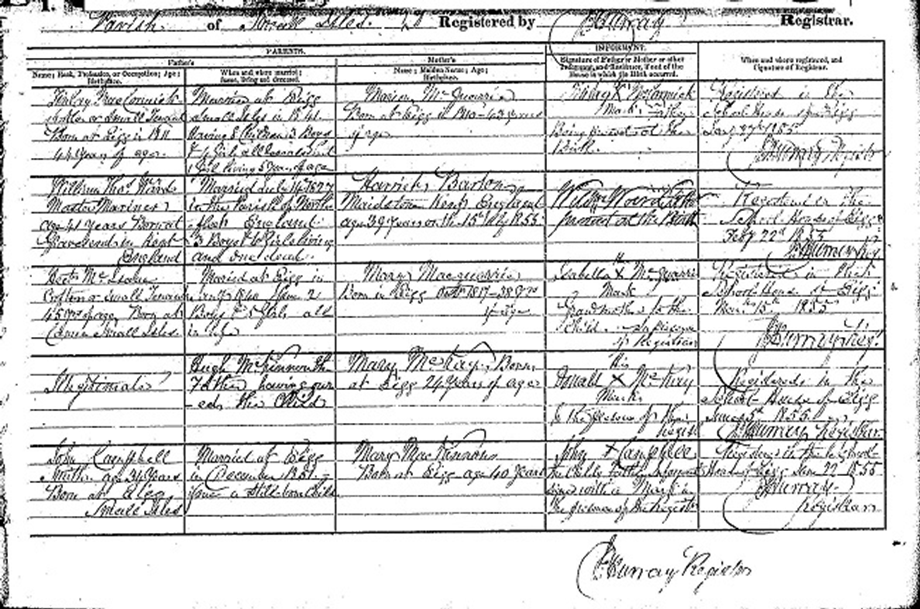

Born May 28th 1855, Galmisdale

On the birth certificate, her father is given as Hugh MacKinnon and the mother as Mary McKay. Mary McKay’s father Donald is the informant on the certificate.

Stealing the names of Gaelic people – one more step in cultural genocide

She was registered on her birth certificate with the name of Christina. She would appear on other certificates with the anglicized names of Sarah, Peggie and Marion. Sarah and Marion are the anglicized versions of Morag. Gaelic names were not allowed on official certificates by law. Things become even more confusing in this particular case. She is called Christina on her birth certificate and Peggie on Donald Campbell’s birth certificate!

In her case, I have found at least four different names used in the official records: Marion, Sarah, Christina and Peggie. However, it is most likely that no one knew her by any of these names, but called her Morag. One wonders why the ‘English’ authorities refused to write the name ‘Morag’? Searching on Google provided a very blunt answer:

“The practice of the law and official systems refusing to recognise the existence of Gaelic went back two centuries. It was rooted in a view that Gaelic was a “barbaric” language; and that if the Gaels were to become civilised they had to learn and use English instead.”

Morag’s daughter, my grandmother Morag McGillivray (nee Campbell) is a similar case in question regarding names. No one knew her as Marion, but as Morag (and perhaps Sarah), yet the records insisted on using the English Marion. As mentioned, this may be considered as one particular aspect of the Anglicisation of Gaelic culture – the refusal by the anglicised authorities to call people by their real Gaelic names.

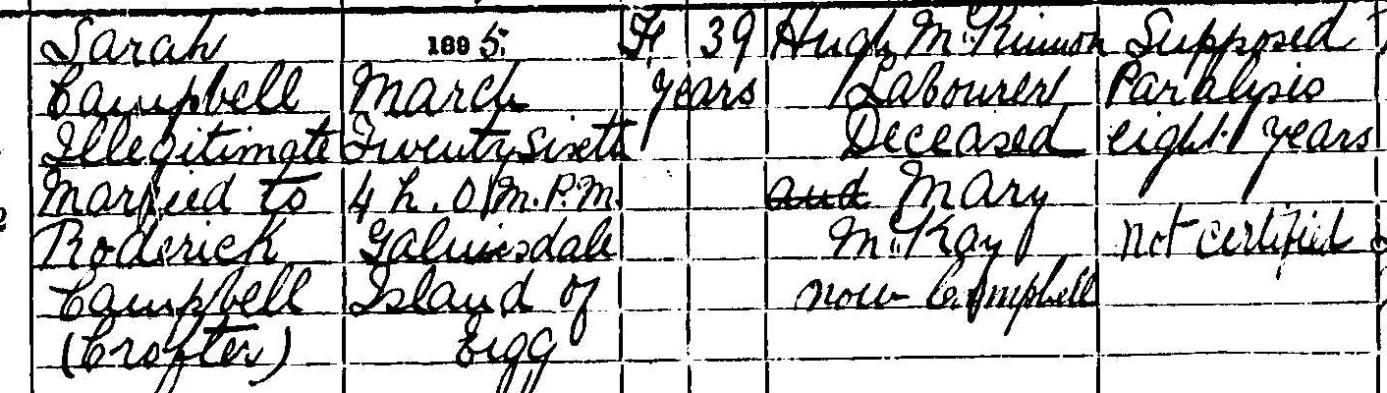

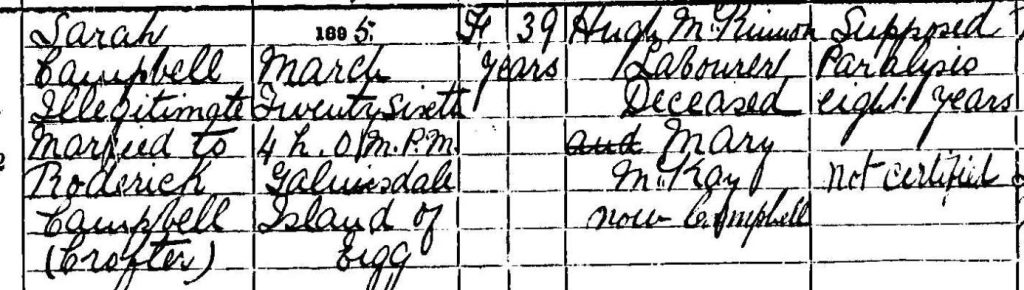

Illegitimacy: the shameful secret – Christian ‘branding’ of children

Christina (Morag) MacKinnon was registered as illegitimate (‘bastard’). Apart from the fact that the anglicized authorities stole Morag’s name, they also decided to brand her for life with the stigma of being born out of wedlock. As if that was something that was her ‘fault’ – a kind of accusation that she should never have had the audacity to be born at all! In other words, the numerous certificates branded her as ‘illegitimate’. Even on her death certificate she was ‘branded’ with ‘illegitimate’ (‘bastard’), as if this stigma would follow her into the grave.

The great malice of the lowlanders

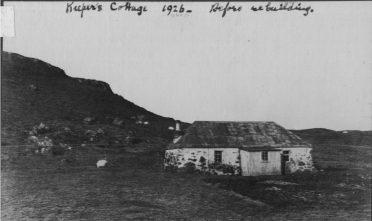

As mentioned elsewhere here, I stayed at Laig Farm in Eigg. However, I only discovered later that the farm has connections to the great Gaelic poet Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair (c. 1698–1770) (legal name Alexander MacDonald, or, in Gaelic Alasdair MacDhòmhnaill). On beginning to read a translation of some of his poetry (see footnote for link), I had only read a few lines before he ‘commented’ on the Anglo authorities disrespect of the original Scottish language. In other words, ‘awareness of culture’ is nothing new. I include an excerpt from his poem.

| ’S de iomadh cànainBho linn Bhàbel fhuairAn slochd sin Adhaimh’S i Ghàidhlig a thug buaidh.Do’n labhradh dhàicheil,An turam àrd gun tuairms’,Gun mheang gun fhàillinnIs urrainn càch a luaidh.Bha a’Ghàidhlig ullamh’Na glòir fior ghuineach, cruaidhAir feadh a’ chruinneMu ‘n thuilich an Tuil-ruadh;Mhair i fòs,’S cha tèid a glòir air chall,Dh’aindeoin gòIs mì-run mòr nan Gall.’ S i labhair Alba,’S Gall-bhodacha fèin,Ar flaith ‘s ar prionnsan’S ar diùcanna gun èis. | Among the many languages which Adam got since the time of Babel, it was Gaelic which won. Everyone can praise majestic loudness, speaking in high respect without guessing, without failing and without fault.Before the Red-flood overflowed, Gaelic was in form, a truly fierce and firm tongue throughout the earth. She still continued. Her glory will not be lost despite the deceit and the great malice of the Lowlanders. It is what Scotland spoke, including to the end the Lowlanders, our nobles, our princes and our dukes. |

Apart from these efforts of the Church and the anglicized authorities to persecute Gaelic people, women, and children born out of wedlock, their perfidious efforts also mean that it has been difficult, if not impossible, to trace my ancestors due to the confusion of names, and the ‘shady’ details regarding the father of illegitimate Morag – Hugh MacKinnon; this is compounded by the fact that Hugh can also be called the Gaelic ‘Ewen’ on some certificates. Apart from these confusions orchestrated by the religious and governmental authorities, there is the added confusion of the replication of both Christian and surnames in Western Scotland, such as the Campbells and MacKinnons, who, although living next door to each other, may not be related.

The 1861 and 1871 censuses

On the 1861 census, my great grandmother, Morag MacKinnon (MacKay) is called Sarah, and is 6 years old. She was living with her grandparents, Donald and Mary MacKay at Galmisdale. The ages of the MacKays from the 1861 to the 1871 census seem to be totally muddled but it must be the same family. It lists their daughter as Christy, and Sarah as the granddaughter now aged 16 years (in 1871). The 1871 census certificate is shown above under ‘Roderick Campbell’ section.

The interesting thing now is that the Campbells are living ‘next door’, and Roderick is listed as being 28 years old. They married five years later when she was 21 years old. Morag’s father is now deceased and is called Ewen (Gaelic) instead of Hugh. She is called Marion on her marriage certificate. As mentioned above, she is also listed as ‘illegitimate’ on the marriage certificate. Roderick is listed as being 30 years old – thus, he has only aged 2 years since the 1871 census five years before!

On the same 1861 census, Jane McKinnon is listed at Galmisdale as being a widow. Perhaps her husband was Hugh, and the father of my great grandmother; but I haven’t done further research here.

Morag’s maiden name was MacKinnon. The spelling of MacKinnon also seems to vary (sometimes spelt McKinnon). As mentioned, her birth certificate reports that she was illegitimate. As also mentioned above, this stigmatic labelling of her by the authorities followed her through life until her death. Her death certificate also records the fact that she was ‘illegitimate’.

In a different part of this book, I have written a story called “The Tale of Morag”. It is a story about Morag Campbell’s life and freely based on oral and written sources. There is also a short story called “Strange Love” by Rory McJoy. It is an alternative version of “The Tale of Morag”, also freely based on oral and written sources.