As mentioned in the ‘Childhood Perils’ chapter, towards the end of the nineteenth century, my Great Uncle Hugh sacrificed his young life in his attempt to contribute to the family economy. Fifty years later in the mid-twentieth century, child labour was still alive and kicking in Britain; however, children were no longer expected to risk their lives. On the other hand, were they expected to risk their health?

In the 1950s and 1960s, kids were expected to help the family economy, or at least subsidise their own upkeep and pocket money. My brothers and I did paper rounds, helped on a mobile grocery shop (which was an old bus), worked in factories, on farms, smallholdings, and so on.

“Potato Picking”

Bending low, hour after hour,

Day after day,

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills,

Where we are earning our daily bread.

The cold smell of potato mould,

The squelch and slap,

Of my wellies being sucked down,

By the wet soggy earth.

“There’s a big one – I’ll grab that,

And put it in my basket.”

Not liking the sticky cold touch of this lumpy fruit of the earth,

And when the mud cracks dry on your hands,

You’re left with an uncomfortable feeling of dirty dryness.

“My God! This is work for slaves or serfs,

I should be somewhere else, scrumping apples,

From the farmer’s orchard,

Rather than working for him almost for ‘free’!”

“I’ve probably picked fewer potatoes a day,

Than any child-slave alive or dead.”

“And when are we going to get a break?

At least he could give us some milk,

He’s got plenty of cows!”

“I’ll be glad to get away from this muddy field,

And go home for tea!”

The cold smell of potato mould,

The squelch and slap,

Of my wellies being sucked down by the earth,

Deaden my thoughts.

“When is it tea time?”

Bob-a-job-week

This may come as a surprise given the tone of the previous piece, but there was a time that we happily worked for free! When we were in the cubs and scouts, we went around the village from door to door asking for work. We did a variety of work such as washing windows, digging gardens, sweeping floors, washing cars, and other manual and menial tasks. It was presented to us like a game, but was actually a fundraiser for a project we knew little about.

We were given ‘Bob-a-job’ cards which we had to fill out every time we did a job. For each finished job, we received ‘one bob’, which was slang for a shilling. It was worth 5p, or about 5 US cents. I still remember the yellow adhesive stickers that we fixed to the house windows to signal that a cub or scout had already done a job at that house. That way, other cubs and scouts wouldn’t knock on their door.

The cub or scout that had the most jobs filled out on their card would receive some kind of prize or award. It was easy to trick us kids! Of course, we all thought we were going to win, so we ran around houses working for free! It was fun earning money; what was not fun was having to give all the money to the scoutmaster in the end!

“Hero of Labour Award”

This Soviet-style ‘Hero of Labour Award” was used to fool children in several contexts – it was just a clever means to make children compete with each other to work the hardest, either for free or for low pay.

My eldest brother, Sandy, was always the ‘Hero’ in this context, and farmers would always invite him back year after year to their fields to do more back-breaking work. I was the opposite, doing everything I could to avoid work.

Over the years, my brothers and I would argue with our parents, mostly my mother, about what share of our wages we should give her for ‘our upkeep’; but this is another story that I will write about later in “Recollections II”. Now, I want to dive into the details of the dirty work of potato picking for a moment.

Cheap child labour

My brothers and I worked for Higgins the farmer, providing him with cheap child labour for many years of our boyhoods. It seems like he and my mother saw a golden opportunity for mutual benefit. Higgins lowered his production costs and outsourcing work to the four Harkness brothers; on the other hand, my mother balanced her strained family budget.

Higgins was a smart ‘Capitalist-Communist’. He introduced to us the ‘Hero of Labour Award’ for the most exceptional and outstanding child ‘slave’; simply, this award is for the one that could pick the most potatoes! My eldest brother, Sandy, was given the ‘Hero of Labour Award’ year after year, which brought great pride to my mother. To her, this meant being a better person than lesser mortals a.k.a us, his brothers. He was always THE model to follow.

Of course, he wasn’t given an actual ‘Award’. He was awarded perhaps £1 more in wages than the other child ‘serfs’. Needless to say, Higgins was not only a farmer, but a shrewd businessman. He understood the importance of motivation. In fact, we were motivated to work harder, but after a while, this strategy came back to haunt him. We finally realised that we would NEVER be able to work hard enough to win the award. However, he was no Jack Ma either, so he didn’t expect us to work 9-9-6, as we had to get home for tea by 6 pm.

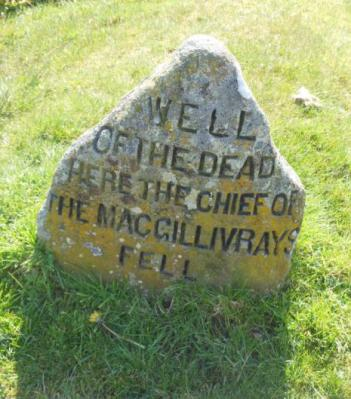

Because of this awarding talk, I got to childishly imagine how our family would be had Nazi Germany occupied Britain. You can read more about that in this post: Nazism in the past and the present.

2 Replies to “Child Labour in Post-war Britain”