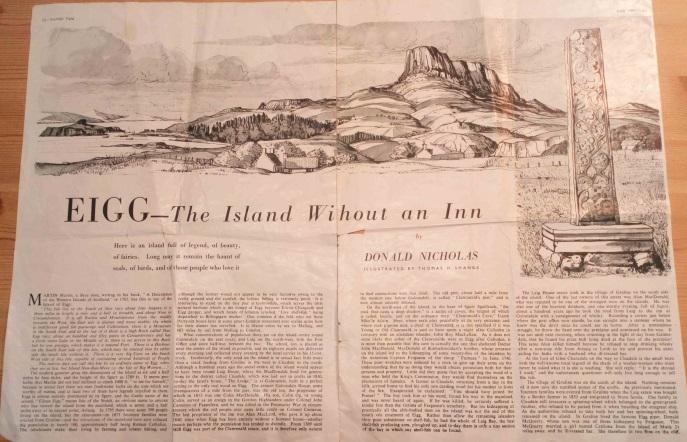

Eigg, the Island without an In: written by Donald Nicholas, Illustrated by Thomas H. Shanks. Scottish Field, June 1951

This first article mentions how Sir Walter Scott visited the cave on the island, “the Massacre Cave”. The whole population of the island were slaughtered by a clan from a neighbouring island some centuries before. This article is written before the ‘hated’ landlord, Schellenberg, and the ‘absent’ landlord, Maruma, appeared; so the article takes on a romantic tone.

Transcription

Martin Martin, a Skye man, writing in his book, “A Description of the Western islands of Scotland,” in 1703, has this to say of the Island of Eigg:

“This Isle lies to the South of Skye about four leagues. It is three miles in length, a mile and a half in breadth, and about Nine in circumference. It is all Rockie and Mountainous from the middle towards the West. The East side is plainer and more arable; the whole is indifferent good for pastorage and Cultivation; there is a Mountain in the South End; and at the top of it there’s a high rock called Sgurr, about a 150 paces in Circumference.It has a freshwater Lake in the Middle of it; there’s no access to this Rock but by one passage, which makes it a natural fort.

There’s a Harbour on the South East side of this Isle, which may be entered into by either side the small Isle without it. A very big Cave on the South West is on the side of this Isle, capable of containing several hundreds of People. The natives dare not call this Isle by its ordinary name of Eigg, when they are at Sea but Island Nim-BanMore, i.e. the Isle of Big Women …”

The modern gazetteer gives the dimensions of the island a six and a half miles by four miles; and the height of the Sgurr is 1289 feet. It seems probable that Martin did not feel inclined to climb one thousand feet “to see for himself”. In actual fact there are nine fresh water lochs on the tops which are worthy of names; and at least two of them have legends attached to them.

Eigg is almost entirely dominated by its Sgurr. The Gaelic name of the island, “Eilean Eige” means Isle of the Notch. It is an obvious name to anyone who has viewed the Island from the mainland; it is seven and a half miles away at its nearest point, Arisaig.

In 1795 there was some 399 people living on the island; but the clearances – in 1853, 14 families were evicted from Gruline. The attraction of the mainland have now reduced the population to barely 100, approximately half being Roman Catholics. The inhabitants make their living by farming and lobster fishing; although the former would not appear to be very lucrative owing to the rocky ground and the rainfall, the lobster fishing is extremely good.

It is interesting to stand on the tiny pier at Galmisdale, which serves the little natural harbour. You could hear the sound of Eigg between Eilean Chathastail and Eigg proper; you may also watch boxes of lobsters labelled “Live shellfish” being dispatched to Billingsgate market. One wonders if the folk who eat these 36 hours later in some smart London restaurant ever realise quite how far their dinners have travelled. It is 15 miles by sea to Mallaig, and 603 Miles by rail from Mallaig to London.

What concentrations of population there are on the island centre around Galmisdale on the east coast, and Laig on the northwest, with the post office and store halfway between the two; the school is placed at as near to the centre of the island as possible; its 18 pupils are delivered every morning and collected every evening by the local carrier in his 15-cwt truck. Incidentally, the only road on the island is in actual fact little more than a track, leading from Gruline in the west to Cleadale in the north.

Although 100 years ago the social centre of the island would appear to have been around Laig house. The McDonald’s lived there for generations in the district called Cleadale, which was laid out in crofts in 1810. Today, the laird’s house, “the Lodge”, is at Galmisdale. It was built in a perfect setting, in the only real wood on Eigg.

The present Galmisdale House, some three quarters of a mile from the pier, was the old inn. The proprietor of which in 1815 was one Colin McDonald. His son, Colin Og, or young Colin, served as an ensign in the Gordon Highlanders under Colonel John Cameron of Fassiefern.He was killed in the Peninsula War, in circumstances which the old people cast little credit on Colonel Cameron.

The last proprietor of the inn was Alan McDonald. He who gave it up about 1840, since then Eigg has been entirely without a licensed house. It was perhaps another reason why the population has tended to dwindle. From 1309 until 1828, Eigg was part of the Clanranald estate. It is therefore only natural to find connections with that chief. The old pier about half a mile from the modern one below Galmisdale, is called “Clanranald’s pier,”; now, it is almost entirely disused.

The village of Gruline was on the south of the island. Nothing remains of it now, save the tumbled stones of the crofts. As previously mentioned, 14 families were evicted from Gruline, when the Laig Estate was bought by a border farmer in 1853. The families emigrated to Nova Scotia. One family in Cleadale still treasures a spinning wheel. It belonged to the great grandmother who refused to be parted from it when boarding the emigrant ship. The authorities refused to take both her and her spinning wheel, so both remained on the island.

In Gruline lived the famous Eigg piper Donald MacQuarry, whose son was one of those kidnapped by Ferguson. This MacQuarry married a girl named Catriona from the island of Muck two and a half miles away; he ill-treated her. She therefore lit two fires on the cliff which were seen by her two brothers on Muck. The came over and beat up the piper and took Catriona back. Poor MacQuarry became very unhappy. One evening he took the pipes onto the cliff and played a pibroch, very long and sad, which brought Catriona over again, and they lived happily ever after.

When MacQuarry died, his bier was carried along the track towards Galmisdale. A boat was seen bringing over the man who had taught him to play the pipes from Arisaig to Kildonnan for the funeral. The bearers waited until he arrived from Kildonnan; he played the pipes without stopping from Kildonnan until he reached the bier; there, the bier rested a cairn was built. It was still beside the track and on to which, on the first time he passes, the wayfarer should put another stone.

This story is told by Hugh MacKinnon of Cleadale, himself descended from Donald MacQuarry. He added a rider to the effect that early in the century when the road was being remade some stones were taken from the cairn, much to the anger of the two road-menders, one of whom was a MacQuarry. They complained to the factor, one McDonald of Sleat, who ordered the stones to be returned to the cairn.

Gruline was the home of another famous Eigg personality, John McDonald (John of the Black Locks), a bard who was born in 1650, and fought at Sheriffmuir in 1715.

John MacDonald, commonly called Iain Dubh Mac Te Ailein, or John of the black locks, son of John, the son of Allan. He was a gentleman of the family of Cian Ranald, born in 1665.

Having received a good education for the age in which he lived, he was a man of considerable ability. He also keen powers of observation. John MacDonald was descended from the Maer family, a branch of the Clan Ranalds, of whom many individuals were highly distinguished for prowess, martial spirit, and poetic powers. He held the farm of Grulean in the island of Eigg, where, we presume, he spent most of his life.

Though not a poet by profession, he was considered by good judges to be not inferior to some of the best bards of his day. Should he never have composed anything but “Oran nam Fineachan Gaelach” it was enough to immortalize his name as one of our great Gaelic poets. Living in fairly affluent circumstances, and amid rural pursuits, he courted the muses only occasionally when the inspiration moved him by some occurrence to record his observations on men and manners. He exhibited poetic powers of a high order, displaying a considerable acquaintance with the power and force of the Gaelic language as a living instrument for depicting passing events with all their poetic, stirring incidents and surroundings.

Had he lived under any other circumstances there is no saying what he might have produced; but his solitary residence on a comparatively remote island in those days, away from the most stirring events that were going on in other parts, left him little choice in the selection of subjects to show the latent spirit and fire of which he was evidently possessed.

We have enough, however, in his poems which have been preserved, to warrant us in concluding that he was a great credit to the noble house of Cian Ranald. His ” Marbhrann do Shir Iain Mac ‘Illean Triath Dhubhart”—lament for John MacLean of Duart—is a long poem of 180 lines; each stanza consiss of 16 lines; about the longest I know, if it were intended to be sung to any air.

I consider his “Oran nam Fineachan Gaelach” (song to the Highland clans) contains as much of the fiery martial spirit as would have done credit even to the celebrated Alasdair Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair (Alexander, son of Mr Alexander). It is by far his best effort, and breathes a warlike spirit throughout. The air to which it is sung has also got a well-rounded measure, which suits the words admirably. In it he describes all the clans, and their respective prowess and invincible qualities in battle. (…).”

Comment on the Article

Interesting to note in the article is the reference to the “15-cwt truck,” which, delivered the 18 pupils to school every morning and collected them every evening. This is very probably the same 15-cwt Fordson truck, called the “Hen Coop” by the islanders. It was referred to elsewhere in this book as the island’s “taxi”, driven by Dugald MacKinnon, the husband of my mother’s cousin, Katie MacKinnon.

Also interesting to note from the article is the story of MacQuarry as told by Hugh MacKinnon. My great-great grandfather was Hugh MacKinnon. But this was another Hugh MacKinnon – although it is highly probable they were ‘blood-related’. At least I like to believe this, as I like to believe I’m carrying on the tradition of Hugh’s ‘storytelling’.

The Hugh McKinnon in the article was a great storyteller and tradition-bearer. He was referred to in many instances in Camille Dressler’s book, The Story of an Island (2007). Dugald MacKinnon, the husband of my mother’s cousin, Katie, was also a great storyteller, as is evidenced in Camille’s book.

Dressler’s book is to a great extent based on oral history, which became popular in the 1960s and ’70s, where interviewing began to be employed more often when historians investigated history from below. Similarly, my book is to some extent based on oral sources.

Hugh MacKinnon of Eigg, crofter and postman

“One of the last great tradition-bearers from the Isle of Eigg was undoubtedly Hugh MacKinnon (1894–1972). He is a crofter and postman, who could trace his lineage back several generations to families such as the MacQuarries and MacCormicks. MacKinnon married Mary MacDonald and had a son called Angus and a daughter Peggy. Both were brought up on the croft, situated in Cleadale to the north of the island; the croft had been in the possession of the family since the mid-nineteenth century.

‘In Eigg I (Calum Maclean) stayed with my writer friend, George Scott-Moncrieff. Our nearest neighbour was Hugh MacKinnon, postman of the island, and one of the most charming characters I have met on this sojourn in the Isles. With him I spent most of my time in Eigg. Every evening for a month I carried my Ediphone on my shoulders across the fields to his house and set it down on his table. Every story he knew, every scrap of local and historical tradition, every song he remembered was sung or spoken into that machine.’ “

Other mentions

The newspaper article also mentions ‘John of the Black Locks’, as well as “The Cave Massacre” which I have also included in this book in historical and semi-fictional forms. It also mentions the slaughter of St. Donnan and his monks. The rest of this article is inserted as images.