My father worked in Burma both as a soldier and civilian. The letters I have seem to relate to when he was a civilian, whereas the photos seem to relate to when he was serving in the Navy. To read the full version of the letters, check out SWALK (Interactive version).

Letter from November 1943

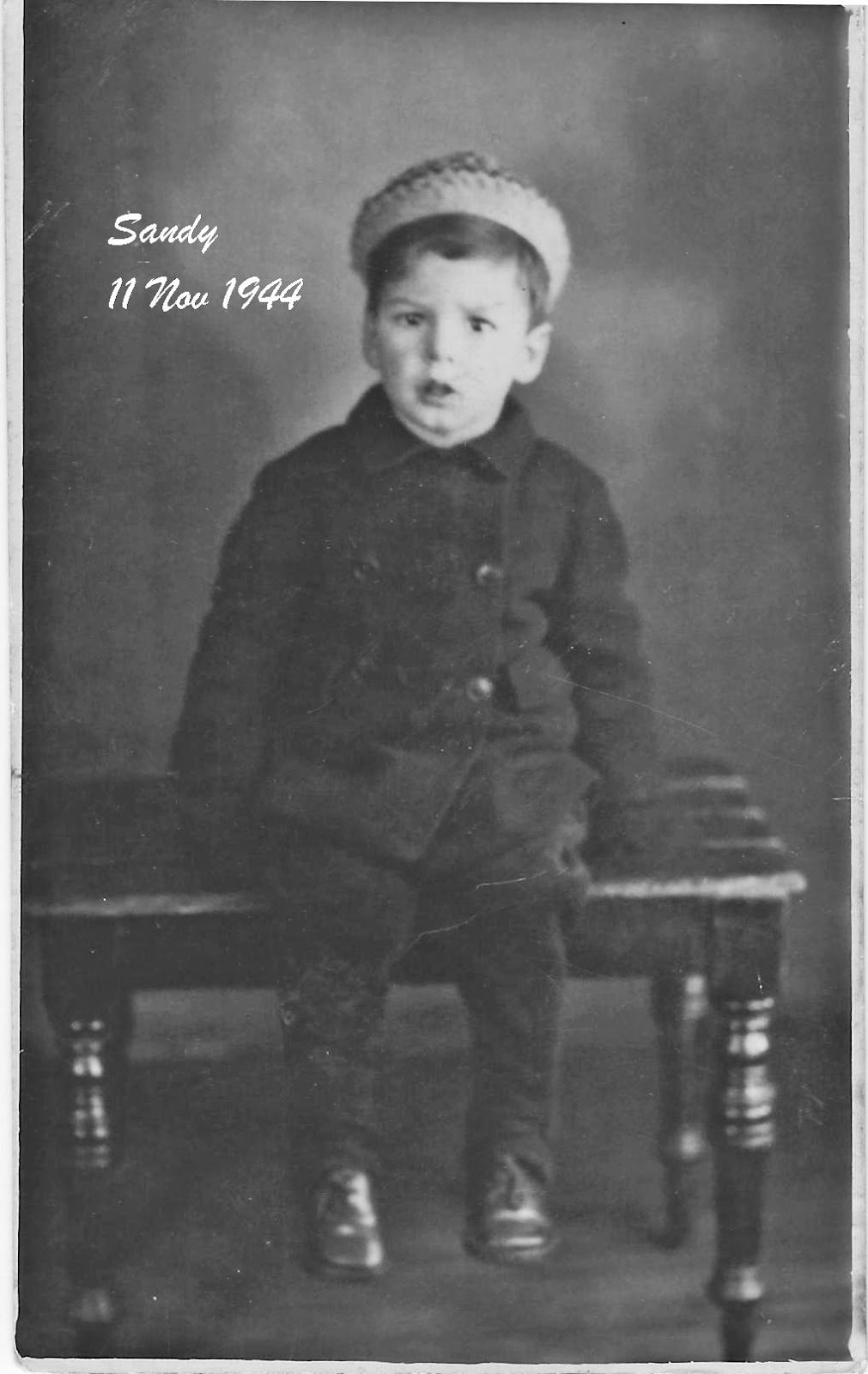

My father mentions ‘March’ – implying the birth of Stuart in 1944. So this letter was probably written in late 1943. He writes:

“I’m writing to tell you something of the bad news to us. After our talks of bringing Sandy and you back to Ardnadam for the winter. I arrived here (…) Weeks had a call from Glasgow to tell him to ask for volunteers to go abroad. Pike and myself were in the office at the time. and he asked if we wanted to go.”

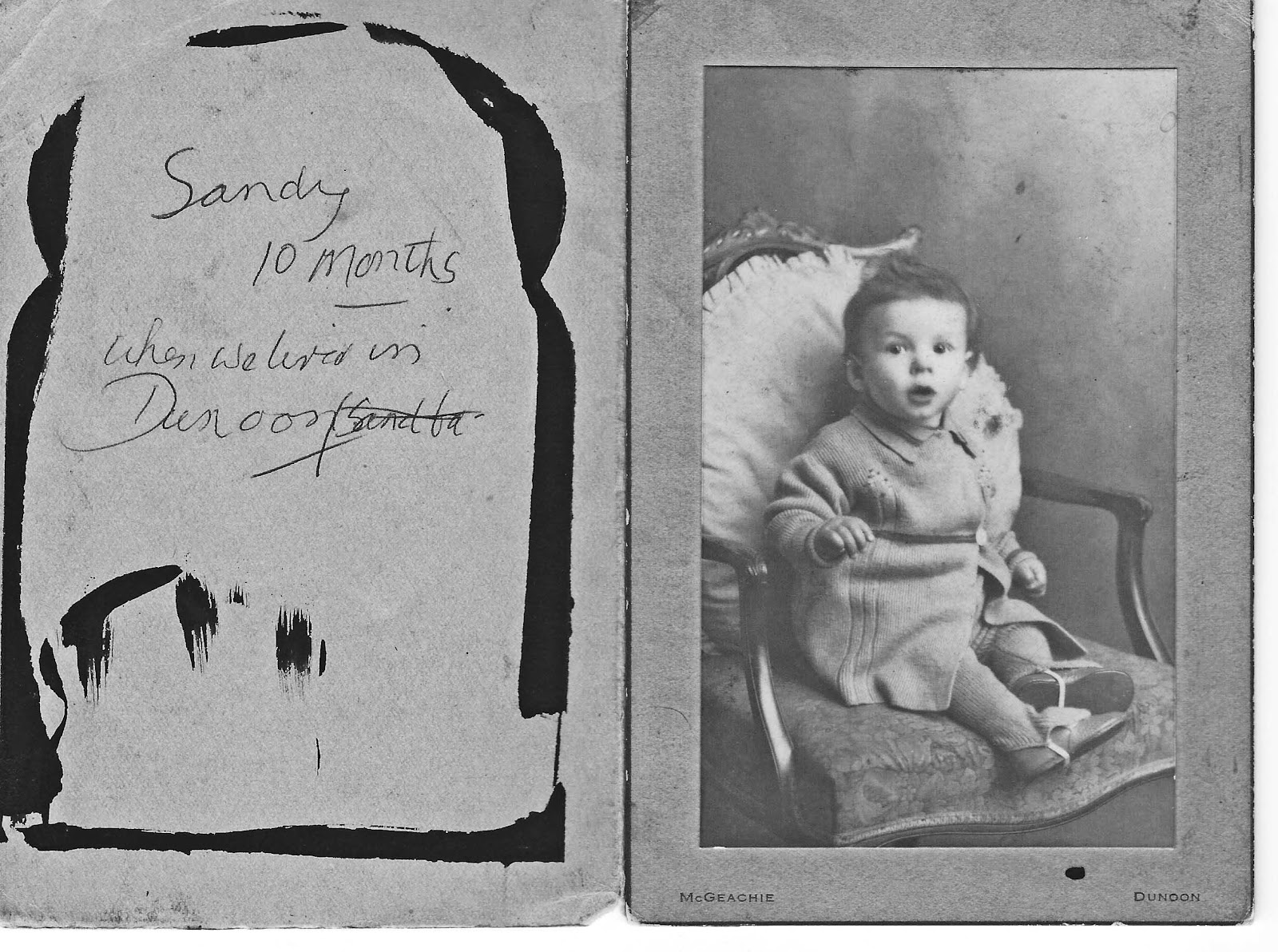

This seems to be a reply to my mother’s 3 November, 1943 letter, where she says: “Do you still want me and Sandy and myself to come to Dunoon?” In other words, he explains in this letter why she can’t come as he is at risk of being posted somewhere else.

I am not quite sure how the RNVR (Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve) functions. But the key word is perhaps ‘volunteer’. So, unlike the regular army, you wouldn’t perhaps be ordered to go here or there, but asked to ‘volunteer’. Without more information, I suspect my father joining the RNVR was a canny move. Despite all the jingoism of WWII, no rational person wants to end up on the end of a bayonet, even if you are promised the favours of the Valkyries in the nether world. My father was too intelligent to fall for such jingoistic propaganda. However, he did ‘volunteer’ to serve in Rangoon Burma.

Admittedly, Rangoon is no Bangkok, but there were probably quite a few available ‘virgins’. I’m perhaps being unfair to my father here, as the main motivation for him volunteering to serve in Burma was perhaps financial rather than other ‘interests’. However, you can’t get away from the fact that colonial soldiers have always been interested in amatory ‘bonuses’, as is shown in Kipling’s poem, “Mandalay”. I go into more detail about that here: My Father and the Last Defenders of the Empire.

It seems the RNVR provided my father with permanent employment, but without being involved directly in hostilities as just so much ‘cannon fodder’. Regarding the request of volunteers to go abroad my father writes that he said, “And I said no later in the day.” In other words, he would answer the request later. But the others volunteered.

He goes on to mention “houses to let” in Dunoon – but it is vague here. He mentions that those who were not going abroad would be shifted elsewhere. My father was shifted to Sunderland around late 1943 – early 1944 probably; thus, there was no point in renting a house in Dunoon.

But the idea of going abroad also appeals to my father:

“I’ll get colonial money which is quite a bit, and I’ll be able to come home and tell you how the girls are out there.”

In other words, this more or less implies that the naval officers had joked about the ‘boons’ of serving abroad.

“Tell you how the girls are out there”

This ‘innocent’ remark of my father’s is a nice phrase covering up the cesspit of war. The abuse of women as a weapon of war is something everyone who reads the news knows something about. However, the idea of sexual abuse of ‘conquered’ women by soldiers is often glossed over or romanticised and sentimentalised.

Letter from 6 September 1946

This seems to be the first ‘Rangoon’ letter he wrote, which wrote from the Highland Princess! But he was in Rangoon around 1945/1946 serving in the RNVR, but there don’t seem to be any letters from this period. The first page doesn’t say an awful lot – then he jumps to page 3?! I can manage to read my father’s scrawl – I wonder if my mother found it so easy?

“There is nothing but lemonade on this ship,” he wrote. I suppose he means they don’t serve alcohol for one reason or another.

Pukkah Sahibs

On page 3, my father mentions ‘pukkah sahibs’, and says they are all ‘hoiti toiti’. This agrees with the views of George Orwell who commented on this in his novel Burmese Days that it was a “pose.” My father then goes on to say, “There are a few white women aboard that are married to Burmese men. They are shunned by the other white women. There is one little English girl married to a Burmese lieutenant (Air Force). I feel very sorry for her.”

This is quite a complicated topic, which Orwell focused on in his novel Burmese Days. He focused on the relationship between white men and Burmese women, which was looked down on by the British colonists. Interesting in this context is the institution of the ‘English club’ in the colonies, which Orwell describes as “the seat of English power.” Colonial subjects had limited access to the ‘English club’.

I delve into this more in No Woman, No Cry Volume I.

The Distance

Page 6 mentions “that you come out here darling.” On reading all the Rangoon letters, it seems that my father had a contract for four years. It was hinted that he could make more money working in Burma, than in Scotland. But the social and political conditions in Burma at this time were unstable; thus, the idea of my mother joining him in Burma never materialised. Moreover, he didn’t stay there for four years. The dates are uncertain here, as mentioned above.

Letter from 13 November 1946

The address of the letter is interesting as it shows where my father worked at 501 Merchant Street for the Rangoon Electrical Supply Co. I haven’t researched this in detail, but a quick search on Google shows that 501 Merchant Street is an old colonial building in downtown Yangoon that has been restored.

The problem with the Rangoon letters is that we do not have the letters written by my mother that she must have sent to my father in Rangoon. However, we can imagine what my mother has written.

Local Burmese Women

“There isn’t much real temptation here – they smell a bit when you get within 3ft.” In other words, my mother had probably asked if he was tempted to be ‘frisky’ with the local Burmese women. Trying to remind him to ‘walk the line’, or in the words of Vera Lynn’s song that “You belong to me” (even though you are wandering abroad).

My father’s response that ‘There isn’t much real temptation here – they smell a bit when you get within 3ft’ doesn’t sound very convincing. After all, why was he within 3 feet and ‘smelling’ them?! It’s comical. It’s part of the colonist’s ‘locker room talk’. On the other hand, this was before the advent of mass produced deodorants. I’m no expert of the diet of the Burmese people, but it is probably very spicy, including garlic and onions, and perhaps also ‘fishy’ food and sauces. Moreover, my father was no perfumed Nancy boy. Rather the opposite.

My mother had complained about his lack of personal hygiene, and that his clothes were full of bugs (see the Bugs Saga)! Furthermore, he smoked a smelly pipe that was so bad that my mother forced him to give up the habit years later. In addition, my father was no ‘namby pamby’, so if he met a young and pretty Burmese girl, I’m sure he wouldn’t let a few garlicky and fishy smells put him off! After all he had been working on fishy, flea-infested boats for several years! (the naval boats, “Young John” and “Girl Ethel” were recommissioned fishing boats).

The Burmese mistress, Ma Hla May

After my mother died in 2010, my brother Gavin ‘inherited’ many of my mother’s documents and memorabilia. Amongst these were some artefacts of my father, including an old ‘Eastern’ wallet.

On opening a ‘secret pocket’ of the wallet, my brother Gavin found a picture of a Burmese girl, with a note saying, “My dear Ma Hla May”. One can only assume this was my father’s mistress in Rangoon.

As mentioned, my father’s reference to ‘smelly’ Burmese women is certainly unconvincing. In other words, a man that sired five boys, and who liked whisky, and who had a volatile temperament, probably had a Burmese mistress or two or three. It was undoubtedly his first trip to Burma as a naval officer that may have given him the taste for Burmese women, so that he returned there later as a civilian.

In his forties he started to work for James Scott in London, which took him to Africa (Addis Ababa in Ethiopia). So, it is not unimaginable that he got up to his ‘old tricks’ there as well. In fact, if one was to over-interpret this, one might imagine he took the James Scott job so he could have more ‘experiences’ abroad. But of course, all this is just surmise.

Random Conversations

On page one my father writes that he used to pull my mother’s nose, and she would get angry – however, I can’t remember him ever doing that. But on page 2, he writes this was mainly when they were first married, and my mother was living in lodgings at Sandbank, Scotland. In other words, they have now been married about six years, so they can start to talk about the ‘old days’.

On Page 3, my father writes: “Veins can be the source of all sorts of troubles for women in later life. Or am I an alarmist?” It seems that my mother has been complaining about varicose veins, which might have developed due to pregnancy. My father advises against an operation. My mother is only 25 years old! So this was perhaps a bit tactless of my father!

Bickering

“Of course darling I love you and the children, and it was for you and the children I left home. So darling try and be patient till I come back. And then I think we will be so well ‘attuned’ to one another that anything like quarrelling and bickering will be a thing of the past, or will that make life too dull for us? I don’t think so! We have three musketeers who will see to it that we don’t have a dull moment.”

My father lets several cats out of the bag in this letter! I think he found married life boring and problematic, but couldn’t ditch his wife and children just because of his dissatisfaction. His arguments are very unconvincing. He didn’t go to work in Rangoon just to make things better financially for my mother. He may have had some financial perks, but his main motivation was probably ‘adventure’. After all, he was still a young man of 30 years old, and wanted to experience more things in life than just family life in Edinburgh. His naval colleagues had also embarked on such ‘adventures’ (written in his other letters).

This letter also seems to indicate that my mother was not an easy woman to get along with! My mother, no doubt, thought that my father was not an easy man to live with either. He has his drinking, and the fact he seemed to prefer the company of his mates over her. Lastly, he also has his ‘hot temper’. I delve deeper into their characteristics on the post:

Incomplete Letter from Autumn of 1946

Yet another incomplete letter – perhaps not ‘incomplete’ but the missing pages have ended up somewhere else in the archive. My father’s script, as usual, is difficult to interpret. But to cut a long story short – my father mentions that colonial service can provide extra benefits.

Moving Abroad

On Page 2, my father writes: “… do so until the conditions here become more settled.” This might refer to the suggestion that my mother can also move to Burma. It seems probable that this letter was written just after the time he arrived in Rangoon – in other words, sometime during the autumn of 1946.

In my other book, “Rhoda’s 1962 Diary”, my parents, like many other British people, dreamed of ‘working for the Empire.’ I talked about their idea of moving to Jamaica. In the days of the British Empire, those of the upper middle classes who had little source of income could find posts abroad working in one of the old colonies.

My Aunt Flora moved to New Zealand with her husband Robert Ralston. My parents’ friends, the Chapmans, moved to South Africa. In other words, working abroad during the post-war period often provided better working opportunities and a higher standard of living than Britain. My second cousin, James Whitecross Harkness, also informed me that I have relations in Canada and Australia. And one of my mother’s aunts also moved to Canada.

Another mention of drinking

“Don’t worry about drink, it’s just a fallacy that you have to drink in the East. It’s only an excuse for drinking. Yours truly will be leading the quiet life here because I think there is opportunity in this firm (…).“

This seems to reply to a letter from my mother that she is worried he will drink too much and live a riotous life. This is probably based on her personal experience.

Another Letter From Rangoon

The cohesion of my father’s letter is certainly a problem – he not only writes in a scrawly hand, but has a disregard for dates and page numbers.

“None of us are enthusiastic at the moment about the place, especially the old hands, because Rangoon as they remember it, has gone forever, i.e. that the Europeans were the masters – the country has practically got home rule etc., and will never return to what it was before the war.”

I could make lots of comments here, but I will rely on the intelligence of the reader. But, I can mention Churchill’s “We shall fight on the beaches” speech, and his reference to the colonies. In other words, British governments have treated colonies differently, depending on their degree of ‘whiteness’. I discussed this in. more detail here: Never Surrender by Winston Churchill

My father also mentions 4 years on the letter, probably meaning he had a four-year contract. This was perhaps cut short due to Burma’s independence struggles. He writes: “This place could be a very pleasant place to live.” He probably had a higher salary in Burma than he could expect in Scotland.

Bringing his family to Burma

On Page 3, My father seems to be optimistic saying that my mother can visit Burma in two years’ time. If I were to read between the lines – I would say that my father is quite happy living in Burma on his ‘own’. I have suggested elsewhere here that my father had caught ‘yellow fever’. Of course, I will give my father the benefit of the doubt – he was undoubtedly supporting my mother during this period, more so than if he had been working in Scotland.

From a ‘male’ viewpoint it was perfect – he didn’t have to argue with his wife – and he didn’t have to bring up his kids. He could go out for a drink with his mates, and now and then meet one of the ‘evil-smelling’ local girls (reference to another letter).

Coming Home to London

On Page 4, my father mentions meeting his wife in a small hotel in London for perhaps a ‘romantic event’. Perhaps he was allowed leave at various intervals. However, how could they have a romantic meeting with 3 kids? This doesn’t seem to be a very well thought through plan on my father’s part.