I was thirteen and blissfully unaware of concepts like “repressive regimes.” But in hindsight, it’s clear: after barely two months at Barstable School, I was already under surveillance. Yes, “watched”, due to some bangers on the bus.

The Act of Terror

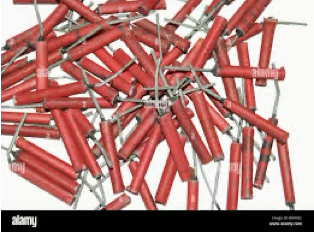

It all began around November 5th—Guy Fawkes Night—when English children celebrate the thwarting of a Catholic plot by gleefully buying fireworks filled with gunpowder and setting them off near buildings, pets, and unsuspecting pensioners. It’s a curious tradition: commemorating an act of anti-government terror by reenacting it annually, complete with sparklers and burning effigies of the Catholic rebel in question.

Of course, at thirteen, I knew none of this. I wasn’t reading history; I was buying “bangers”. These were legal explosives sold freely to any boy with a shilling and a mild disregard for adult authority. And naturally, in a bid to impress my new schoolmates, I ignited one and chucked it out the bus window during our daily commute from Billericay to Basildon.

Unfortunately, the bus conductor had a sense of civic duty that would have made Orwell blush. Spotting my Barstable uniform, he reported me to the school like a good Party member.

A few days later, during morning assembly, Headmaster G.G. Blackhead—a man of Quaker faith and medieval discipline—took the pulpit. His voice, grave and theatrical, echoed through the hall.

“It has come to our attention that a newly enrolled boy has committed a dangerous act of terror upon one of the Basildon buses. This individual—who shall remain nameless—purchased fireworks and, whilst on public transport, hurled said explosives out the window, endangering the lives of pensioners on the pavement below. It is only by the grace of God that none of them suffered cardiac arrest (or spontaneous combustion).”

Spontaneous combustion wasn’t mentioned, but it was implied.

Naturally, I shrank in my seat. It was like being an extra in “The Devils of Loudun”—except with less fire and more polyester uniforms. He didn’t name me, which was oddly generous, but this omission didn’t fool my busmates—Doyland and Cook gave me sideways glances of knowing betrayal. They’d witnessed my war crime firsthand. Still, the rest of the school was mercifully ignorant. To them, I was just another “new boy.” An anonymous terrorist in regulation grey.

What made the whole spectacle comical in hindsight was the sheer melodrama. No pensioners had been harmed in the igniting of this banger. In fact, I’m fairly certain the only person endangered was me—by the sheer force of Blackhead’s righteous fury. And yet, it was all treated as if I had attempted to single-handedly assassinate the Prime Minister using Woolworth’s merchandise.

Ironies Upon Ironies

There was a bitter layer of irony in all this: my poor mother had fought hard to get me into Barstable School. The headmaster had reluctantly agreed to my enrolment, perhaps already sensing that I wasn’t quite the docile type. It’s possible he regretted that decision as soon as the metaphorical—and literal—smoke cleared.

What made this even more ironic was that Blackhead was a Quaker. Yes, a Quaker: member of a religious group that once defied authority, resisted war, and promoted peace. You’d think he’d admire a little rebellious spirit. But alas, Blackhead’s pacifism stopped at the school gates. He had no qualms about corporal punishment or public shaming, especially when applied to small boys with poor impulse control.

In retrospect, I suppose I was ahead of my time—channeling a nascent spirit of rebellion that would blossom at Woodstock seven years later. Except instead of Hendrix and hash, I had a school blazer and a packet of bangers filled with gunpowder.

Let me be fair: my disdain isn’t truly for Quakers themselves. They’ve historically stood for peace and against political tyranny. But in Blackhead’s case, religious convictions seemed to bend conveniently to the institutional expectations of the time; namely, that headmasters should rule by fear, and occasionally by cane. A Quaker with a paddle is a contradiction only the British school system could produce.

The Twist

Years later, long after I’d left Barstable and stopped lobbing small explosives at unsuspecting pedestrians, I learned something remarkable. The very bus conductor who had reported me—the man who had sparked my public crucifixion—later became a Labour councillor in Basildon. He was celebrated for his tireless campaign against “antisocial behaviour” among youth. I suppose I was just a formative experience on his résumé.

So there it is: a moment of teenage folly, inflated into moral panic, quietly folded into the annals of school discipline and municipal politics. And to this day, every time I hear the pop of a firework, I half expect to be summoned to morning assembly once more… accused of almost assassinating a pensioner with a two-penny banger.