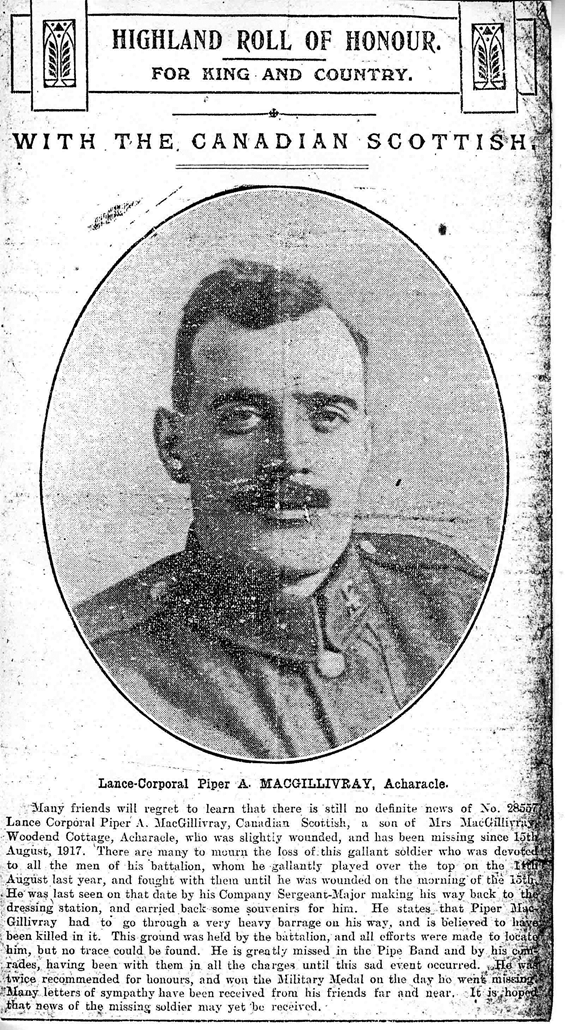

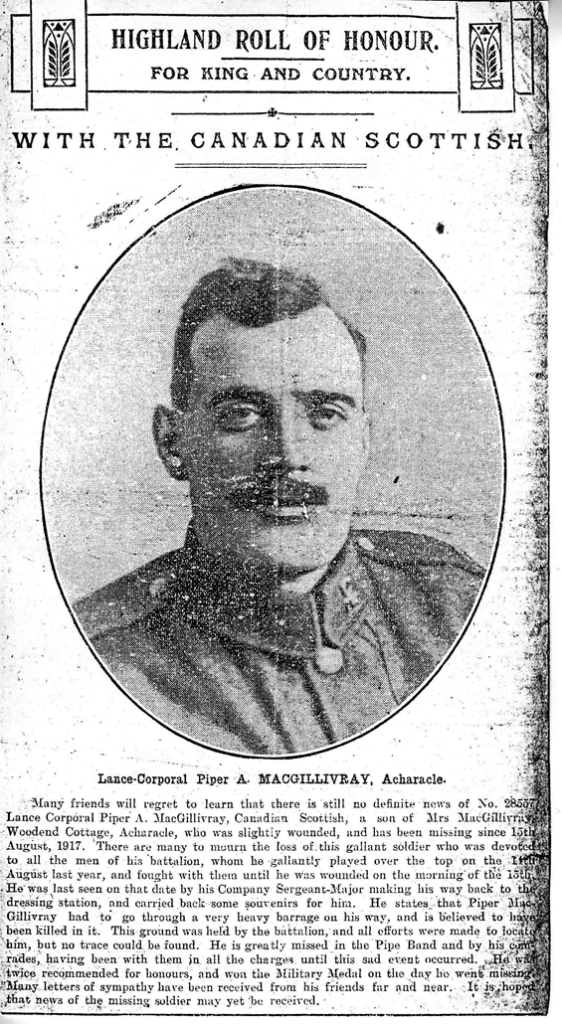

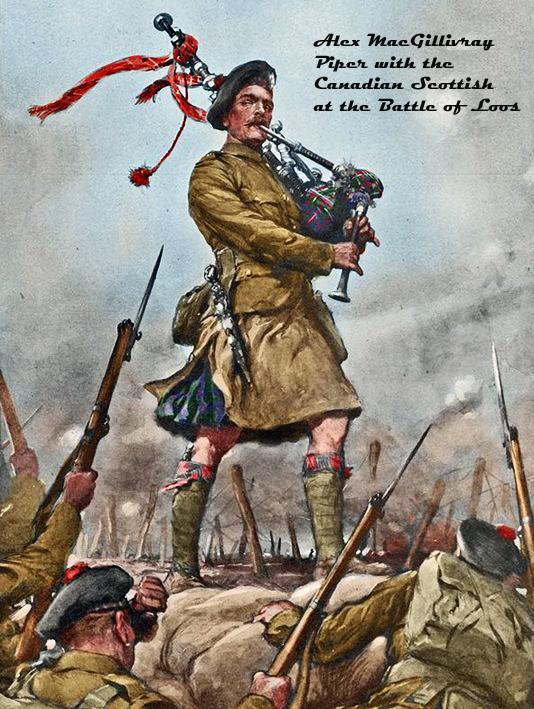

Of course, I can’t go into long descriptions of the battles of World War I here, but it seems somewhat thoughtless to just sidestep it. But I will focus more on this below. In this post, I described the military career of the piper, Alexander MacGillivray. He was Hector’s brother, and Morag’s brother-in-law, and my grand uncle.

Once again I will refer to information sent to me by others members of my extended family, more specifically, Dawn Driscoll and Ted Moyes, my cousin and second cousin, respectively.

Alex was a piper in World War One. As mentioned, both Ted and Dawn have sent me a lot of information about his military exploits in World War One. I have searched on Google, and also found lots of information. In fact, one might say this is a question of ‘information overload’. I will edit the information I have found from this website.

Getting to know Alexander MacGillivray

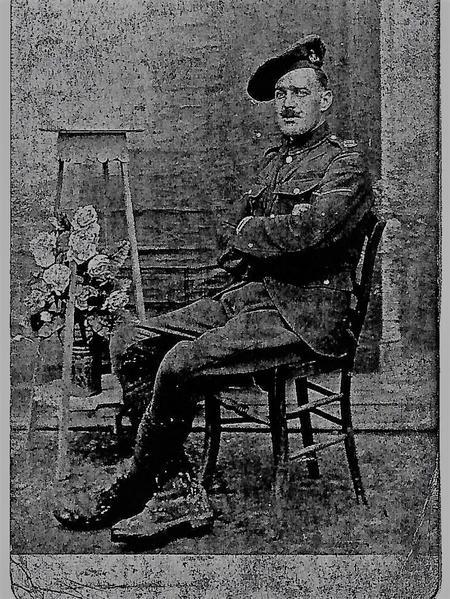

Well, Alex was undoubtedly a handsome man and quite impressive! I found another photo on another website:

LCpl Alexander MacGillivray MM a piper killed at Hill 70 who refused to draw lots. He would go in anyway. Any piper who had grounds for suspecting he had been discriminated against in the ballot, taunted his comrades with injustice, and insisted on accompanying the attacking troops. Brave men, who met death when it came to them unflinchingly.

Acharacle

Alexander MacGillivray, son of John and Flora MacGillivray, of Woodend Cottage, Acharacle, Argyllshire, Scotland. Born 5 January 1888 in Acharacle, Argyllshire, Scotland. He was a labourer and single when he came to Canada and enlisted with the CEF.

Private Alexander MacGillivray 28557 enlisted 23 September 1914 at Valcartier, QC, Canada with 72nd Regiment, Seaforth Highlanders. A big man, standing 5′ 10″ tall, 175 pounds, with fair complexion, blue eyes and brown hair. Immediately placed on 16th Battalion paylist.

16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish)

The 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish Regiment) organized in Valcartier Camp in September 1914, composed of recruits from Victoria, Vancouver, Winnipeg and Hamilton. Commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel R G E Leckie. Embarked Quebec 30 September 1914 aboard SS ANDANIA, and later disembarked England 14 October 1914 with a strength of 47 officers, 1111 other ranks.

Private A MacGillivray appointed Lance Corporal in the Field, 10 March 1916.

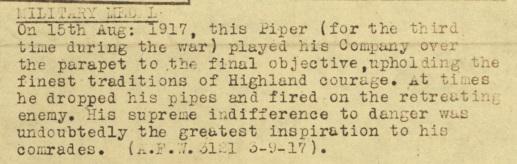

Military Medal – LCpl Alexander MacGillivray MM

Pipers

The pipers came up to their usual standard of coolness and gallantry. Before the attack started, Piper Alexander MacGillivray told the sergeant major, in confidence, that he felt “anxious”. He was afraid that, burdened as he was with his pipes and equipment, there might be a chance of the company men scrambling out in front of him; and so – to use his own words – “bring disgrace on a Highland piper”.

“Well, if you think that way,” said the sergeant major, “ask the company commander to allow you to climb out before us.” This the piper did; and when the barrage opened he led off the advance, well ahead of the attacking wave, playing his pipes.

Blue Line

LCpl Alexander MacGillivray’s gallantry in the assault a source of inspiration to the troops on a wider battle front than that of the 16th. At the “Blue Line” when the Brigade attack reforming under fire for the further advance this piper played without ceasing. He marched up and down before the 16th companies and then strode off to the front of the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada) where, as described in the following extract from the history of that Battalion, he made a profound impression:—

“Just at this time,” the story reads, “when all ranks feeling the strain of remaining inactive under galling fire, and when the casualties had mounted to over 100, a skirl of the bagpipes heard, and along the 13th front came a piper of the 16th Canadian Scottish. This inspired individual, eyes blazing with excitement, and kilt proudly swinging to his measured tread, made his way along the line, piping as only a true Highlander can when men are dying, or facing death, all around him.

“Shell fire seemed to increase as the piper progressed and more than once it appeared that he was down, but the god of brave men was with him in that hour, and he disappeared, unharmed, to the flank whence he had come.”

Final objective

McGillivray was also one of the men who overshot the final objective. When well ahead of the rest of his comrades, set upon by a German. To defend himself he dropped his pipes, and later, when his enemy disposed of, could not find them. He was very much worried over this loss and refused to go back to Battalion HQ, as all pipers had orders to do immediately the assault was over. Ultimately persuaded to return on the promise by the company sergeant-major that he personally would look for the pipes and take charge of them. The sergeant-major found the pipes next morning about forty to fifty yards in front of the final objective.

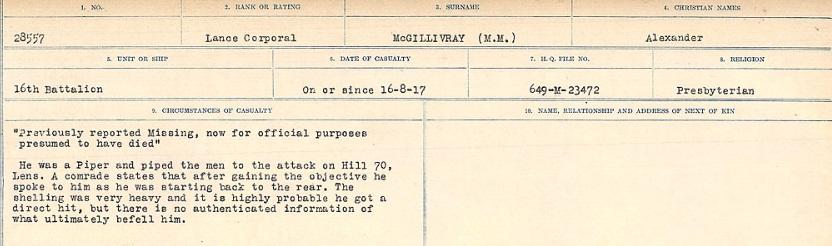

CoD – LCpl Alexander MacGillivray MM

He brought them back with him, but Alec McGillivray was not there to claim his beloved instrument. Seen to start from the front line on his return journey and then disappeared entirely from view – probably blown to pieces by a shell.

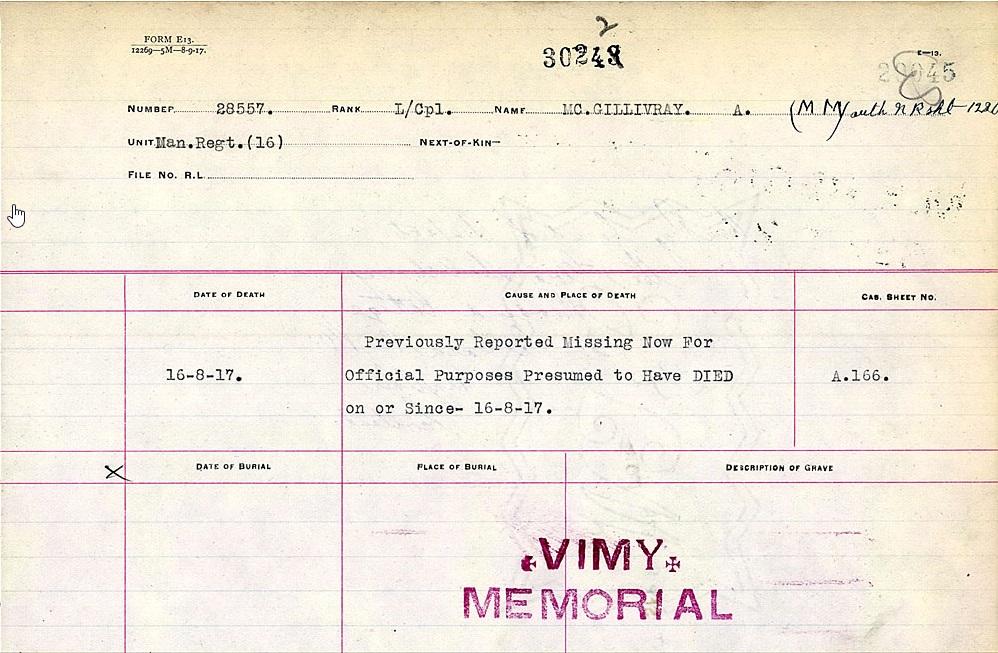

Vimy Memorial

LCpl Alexander MacGillivray MM commemorated on the Vimy Memorial – the location of his remains unknown.

War Grave Register – Lance Corporal Alexander McGillivray MM

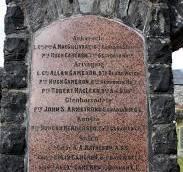

L/Cpl MacGillivray’s memorial tablet located just a few yards from the croft in Acharacle where his family live to this day. I found this on the Internet, but the image quality is very poor.

Alex MacGillivray – World War I piper

Alexander led his men over the parapet, at the front of the men playing his pipes to inspire them to ‘courageous deeds’. The parapet was the protective wall or earth defence along the top of a trench or other place of concealment for troops in World War One.

Passchendaele

Passchendaele is a small village in Flanders. It’s become symbolic over the past hundred years as the ultimate expression of meaningless, industrialised slaughter. In the summer of 1917, the Allies gained five miles of ground in three months and six days. Upwards of 500,000 men were killed or wounded, maimed, gassed, drowned.

My cousin Dawn wrote the following:

“Iain found and also gave me a copy of the story of the ‘Pipe Band of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish) C.E.F.’ which tells the story of that battalion and Alexander, leading up to the Battle of Passchendaele, where our great uncle fell.”

The many gruesome battles of World War One were documented by the ‘war poets’. I will include a poem by Siegfried Sassoon, especially as it makes a direct reference to the Battle of Passchendaele.

Memorial Tablet

Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight,

(Under Lord Derby’s Scheme). I died in hell—

(They called it Passchendaele). My wound was slight,

And I was hobbling back; and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duck-boards: so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

At sermon-time, while Squire is in his pew,

He gives my gilded name a thoughtful stare:

For, though low down upon the list, I’m there;

‘In proud and glorious memory’… that’s my due.

Two bleeding years I fought in France, for Squire:

I suffered anguish that he’s never guessed.

Once I came home on leave: and then went west…

What greater glory could a man desire?

The poem by Siegfried Sassoon perhaps needs no comment. Nevertheless, I will quote a brief meaningful analysis.

“”Memorial” is a scathing indictment of the glorification of war. Sassoon’s blunt language exposes the horrors of trench warfare and the hollow nature of wartime tributes.

Compared to other war poems, “Memorial” stands out for its stark depiction of death and its focus on the individual experience. It reflects the disillusionment and anti-war sentiment prevalent during the time period.

The speaker’s bitter tone conveys the profound anguish of those who have witnessed the true face of war. The contrast between the speaker’s grim fate and the Squire’s comfortable existence highlights the hypocrisy of those who remain detached from the realities of the battlefield.

“Memorial” serves as a powerful reminder of the futility and devastating consequences of war.”

The poem provokes many questions. What is the point of history? What is the point of a family history?

To answer the first question one might say that history helps people to understand how events in the past made things the way they are today. With lessons from the past, people can perhaps avoid mistakes in the present and in the future. So far so good. Obviously, state-run and private nurseries and kindergartens provide better care for children away from their parents, than the baby farmers of the nineteenth century (described elsewhere here). So perhaps humanity is making progress and learning from the mistakes of the past

However, this answer is too simple. Also, the explanation given above regarding ‘what is the point of history?’ is also a little superficial. History is often written to glorify, kings, rulers, nations, religions, ideologies, and so on, and is thus highly subjective. In fact, history doesn’t teach us anything in many cases, but just supports the prejudices of the past, in order to allow humanity to commit the same mistakes in the future. The problem here is the concept of ‘history’. As mentioned elsewhere here, there is no such thing as ‘history’. History is often written by intellectual lackeys, who are no more than prostitutes in the service of some king or other.

One of many such ‘subjective’ histories is “Sverris Saga”, one of the Kings’ sagas, about King Sverre Sigurdsson of Norway (r. 1177–1202). The work was initiated in 1185 under the king’s direct supervision. The saga was written by Karl Jónsson who was ‘sympathetic’ to Sverre’s cause, as he was in the king’s service.

But to return to the second question: What is the point of a family history? One might say that we tell the events in our life the way we saw and felt about them. Family history makes us real to future generations.

Of course, this answer is a little superficial. It might be said that family histories resemble the histories of the kings of the past. The whole idea of the ‘family tree’ is obviously taken from the trees of kings, not to mention the various ‘trees’ in the Bible, and other historic texts. In other words, family histories are often subjective, ‘glorifying’ and skewed. But there are many kinds of family histories.

“The Diary of Anne Frank” is certainly not written as a ‘glorification’ of her family. In fact, it has been interpreted as an implicit indictment of the Nazi regime. One wonders how many ‘Ann Frank’s diaries’ are being written in Palestine and the Ukraine today (2024), as an implicit indictment of present-day Nazi regimes.

The point I’m trying to make here is that a ‘family history’ does not have to be only a subjective and sentimental glorification of one’s own family. I have to admit that this book is highly personal and subjective; nevertheless, I attempt to include a comparative historical aspect.

Glorification of trench warfare – Remembrance Day

The above discussion has been a roundabout way to approach the comparative historical element. Does Remembrance Day glorify war and trench warfare? Obviously, we can’t enter into a long discussion of this question here, but it is nevertheless an important question.

The present-day autocratic Empire of the Rus’ has glorified its invasion of its little brother, and is using the trench warfare tactics of World War One, where men are mere ‘cannon fodder’, so called ‘meat-grinding tactics’. The goal of the Rus is to commit fratricide, to murder their ‘little brother’. The goal is to build a new ‘Empire of the Rus’, but Ivan the ‘wanna-be’ Terrible is not up to the task.

The point I’m trying to make with the above discussion – is to ask the question: Does humanity learn from its past mistakes? Sometimes yes, sometimes no, as is evident from the US and UK-backed invasion of Palestinian territories, and the US funding of genocide in Palestine. The latter is morbidly ironic considering the US criticism of China committing genocide against the Uighurs.

Hypocrisy, Thy Name is America! In other words, what we are seeing in 2024 is Western hypocrisy in the Middle East, or more specifically US and British hypocrisy. Thus, regarding the above, humanity, or more specifically, nations, haven’t learnt a damned shit from their past mistakes; on the contrary, new ‘mistakes’ are being piled on top of the old ones.

To sum up, after this digression, the military accounts of Alexander MacGillivray, the piper in World War I, obviously represent a kind of glorification, in the same way Piper Laidlaw was glorified by the press.

London Gazette, 18 November, 1915. For most conspicuous bravery prior to an assault on German trenches near Loos and Hill 70 on 25th September 1915. During the worst of the bombardment, when the attack was about to commence, Piper Laidlaw, seeing that his company was somewhat shaken from the effects of gas, with absolute coolness and disregard of danger, mounted the parapet, marched up and down and played the company out of the trench. The effect of his splendid example was immediate, and the company dashed out to the assault. Piper Laidlaw continued playing his pipes till he was wounded.

My purpose here is not to denigrate the achievements of my great uncle, Alexander MacGillivray, but to give a balanced presentation, for instance, in relation to the poem written about the horrors of Passchendaele by Siegfried Sassoon. Most of the men who fought in the two world wars had no choice, just as the soldiers of today’s wars (2024) have no choice. The great irony is that they often believe they are ‘fighting for freedom’, but have no freedom of choice. The question that arises here is, as mentioned above: Has humanity really learnt from history so progress can be made?

‘Progress’ has certainly been made from the days of stone axes and wooden arrows in terms of technology. In the distant past, men could only kill each other in the hundreds or thousands. Today, with the use of nuclear weapons, biological and chemical weapons, and AI-powered weapons, they have the capability of destroying billions, and perhaps wiping out the whole of the human race. This is progress indeed!

I wrote more about Alexander, the Piper in this post.