This post focuses on the impact war had on women, as well as the interactions between war and women throughout the years.

War, what is it good for? Absolutely nothing! Say it again!

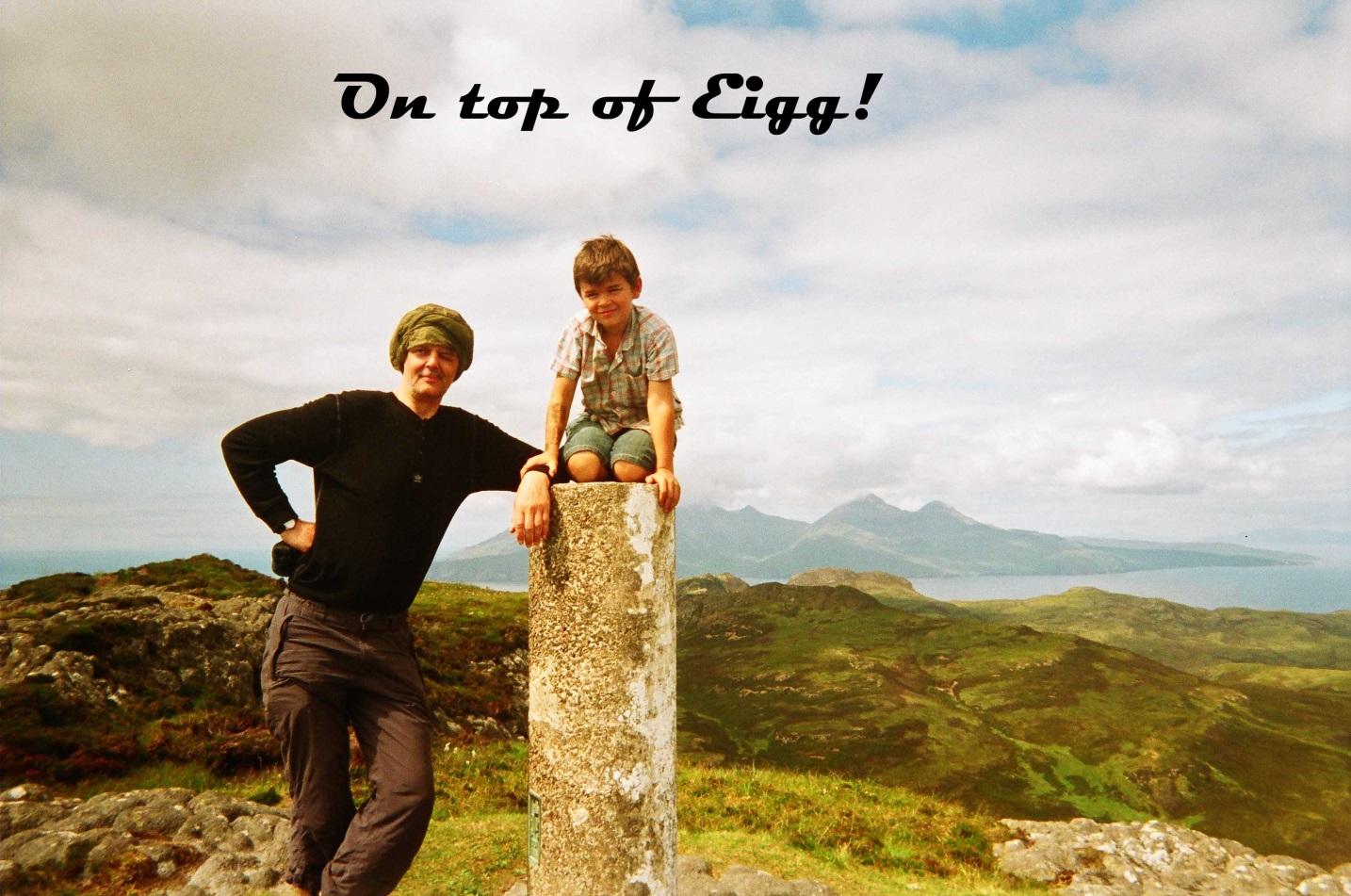

After 1900, changes in agricultural production resulted in people leaving the island. As mentioned, of Roderick and Morag’s children, two stayed on Eigg, and three moved away. Morag left the Isle of Eigg when she was about 18 years old, around 2010, about four years before the start of World War I. According to my mother, she was a nurse for a short while, but didn’t like it. She then became a land girl and a tram driver.

Some readers have perhaps heard the song, “War”. Edwin Starr sings, “War, what is it good for? Absolutely nothing! Say it again!” Well, I’m afraid to say I have to disagree with Edwin.

War is good for many things. Of course, millions are killed and injured, and millions die from disease and starvation. But the two world wars of the twentieth century did not halt global population growth; I’m not saying that World War III will be the same; this might be a case of “things are different this time”. But to return to the working life of my grandmother, Morag, she would probably have struggled to find a well-paid job on Eigg at the beginning of the 20th century.

The two world wars provided many women with jobs that had previously been carried out by men. As mentioned, my grandmother was a land girl and a tram driver during World War One. Both these jobs were ‘created’ by the war.

Women’s rights

Many historians believed the world wars promoted women’s rights and freedoms. Without going into a lengthy debate on this topic, I will just include a brief quote on the topic here:

During the First World War, women stepped into men’s jobs for the first time ever, thousands of women served abroad on the front lines, women’s football even became a hugely popular sport, and the war is thought to have strengthened their case for the right to vote. But how far did the war really impact women’s lives and women’s rights, or was it all ‘for the duration’?

Land girls

Who were the land girls?

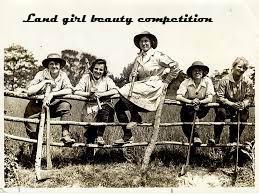

“The Women’s Land Army (WLA) was founded in 1917 to help farmers cope with the shortage of male labour that resulted from the First World War, by recruiting women to work the land. Its members were affectionately known as the Land Girls. Sceptics did not believe that women would be suited to the hard labour that farm work required. But the Land Girls played a critical role in supporting the country’s food production during the First World War. (…) and the critics were proved wrong.”

Morag probably found this job relatively easy, as the girls and women of Eigg were also involved in hard agricultural work.

Neil Munro’s “Land Girls”

I recommend that the reader should stop reading this post and instead read Neil Munro’s short stories, especially his “Land Girls”; this will give the reader a much more in-depth and humorous understanding of the land girls; not least regarding the opponents to the land girls, particularly regarding their right to work and the right of women to vote.

The characters of Munro’s Para Handy short stories give a humorous approach to the ‘fiction of manners’; the various characters of the boat, “the Vital Spark” present contrasting views regarding the customs, values, and mores of the age in which the short stories are set.

The authorial voice emerges when the character with views unsympathetic to the author’s view is the one that ends up being the ‘butt of the joke’. In other words, Munro is able to target the reactionary social forces of the age without going into a ‘political rant’.

My ‘little’ brother Gavin is at this moment in time reading my various biographical books. He suggested that I should read Neil Munro, thus implying that I should avoid political ‘rants’. Moreover, he posted me Munro’s “Para Handy – Collected Stories” (Birlinn, 2022). This is a very interesting book, but I don’t know if I’ll ever manage to read all the stories!

I couldn’t agree with him more. I hate my own ‘rants’ ha ha. ☺ But I can’t afford the space of Munro; that is, concocting a fictional scenario with characters that have opposing views. In addition, I don’t have to ‘worry’ about the opinions of my readers (as he had to do, as he was a journalist). Moreover, I sometimes believe it is best to ‘call a spade a spade’ and not ‘beat about the bush’. Let’s face it. A few modern readers will be able to unravel the implicit social and political criticisms embedded in his “Land Girls”.

However, I won’t bore the reader with my cursory analysis; they can read the story for themselves here.

Did the ‘Land Girls’ wear trousers?

I don’t intend to do a thorough historical research here regarding the sources of the short story. Nevertheless, will nevertheless comment on some points,

“Amazing young women! It was the first time Para Handy and his crew had seen their kind. Those girls, in their corduroy breeches, leggings, strong boots and smocks, with their bobbed hair, and Englified accent, made as much sensation as if they had been pantomime princesses.”

This section refers to the fact that the land girls wore trousers. The photo of the land girls shown here seems to show that they actually wore trousers. As mentioned, I won’t attempt to research this rigorously; but it seems that the Land Girl era was one of the first times where it became acceptable for ladies to wear trousers due to the practical nature of their jobs.

In fact, this is perhaps the main ‘comical’ theme of the short story. This relates to the idea of ‘who is wearing the trousers’; that is, who is in charge, the one who is making the decisions. Of course, women in the 1800s weren’t the ones making the decisions, so this represents a historical watershed.

These girls are not only wearing trousers, but also, like men, swearing and smoking cigarettes:

“They were not unconscious of the impression they created. They put, accordingly, a lot of sheer swank into their handling and hauling of the timber; one or two boldly smoked cigarettes; a little plump one, apparently known as Podger, who had come from a Midlothian Manse, actually stammered out a timid “d-d-damn!” in the hearing of the crew, and blushed furiously as she did so.”

Cigarettes enabled ‘progressive’ women to challenge male social norms, and “fight for equal rights,” the same as men. Eventually for women the cigarette came to symbolize ‘rebellious independence, glamour, seduction and sexual allure for both feminists and flappers’.”

Votes for women

“That’s the latest style, sunny boys,” intimated Hurricane Jack, with all the assurance of a man of the world, up to date in all new movements. “First the vote and then the breeches. Ye can see them’s no common carteresses–born ladies!”

This is a little unclear, because I had imagined the story is set in World War One, but women were not given the vote until 1926. However, it seems there was limited suffrage for women before 1926:

“During 1916-1917, the House of Commons Speaker, James William Lowther, chaired a conference on electoral reform which recommended limited women’s suffrage.”

In other words, this was certainly a topical debate during this period.

As mentioned above, it is a difficult task to analyse the political and social inferences of the short story without a sound knowledge of the historical period. But the author introduces the idea that the Bible in no instances mentions the fact that women should wear trousers: “There is not wan word aboot women wearin’ breeches between the two boards o’ the Bible.”

As mentioned, without going into a thorough analysis of the story, and the political and social climate of the period, this seems to imply that the Church was opposed to the ‘liberation’ of women during this period. The reader can make their own searches on the Internet to confirm this. But a brief search on Google provided the following: “The Roman Catholic Church was the religious group that most consistently opposed women’s suffrage.”

I would love to adopt Munro’s didactic approach to ‘educating’ readers in a roundabout way. However, within the confines of this book, this would prove a difficult task; it is often best to call a spade a spade. In other words, you don’t need to adopt fictional and roundabout ways to call Adolf Hitler an enemy of humanity. Although history and politics are complicated subjects, where it doesn’t always pay to play the ‘blame game’, in some instances this is unavoidable.

Tram driver

When my mother told me many years ago about her mother Morag working as a tram driver, I didn’t think much about it at the time. On the whole, my mother, Rhoda, didn’t have ‘warm’ remembrances about her mother, and accused her of being abusive and ‘anti-social’, a flirt, and so on. My mother didn’t make a ‘big thing’ about her mother working as a land girl and a tram driver during World War I. However, it is obvious that Morag was ‘heroic’ in that she took on difficult jobs normally reserved for men. In other words, she was a ‘feminist’, although perhaps not intentionally.

The great irony here is that my mother hated feminists and other ‘radicals’. The double irony is that my mother was also an unintentional ‘feminist’. She was the one who managed our family. And later in life, she took the brave step to become a teacher, which provided her with an income after her husband died. Another irony is that her great aunt, Ann MacGillivray, was also a teacher around 1900. It was at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. But I’m not sure if my mother even knew of her existence.

In other words, while Morag was working as a land girl and tram driver, during World War I, her Aunt-in-law Ann was working as a teacher in Argyllshire (Ardtoe School). But to return to Morag the tram driver, thousands of male tram drivers volunteered to fight in World War I, creating a labour shortage. This resulted in the ‘weak’ and fair sex being employed in such positions.

Eliza Orr – the first woman tram driver in Glasgow in 1916

During World War One, women had large families and housework that could take all day long. However, this didn’t stop women applying in their thousands to work on Glasgow’s trams. Despite their back-breaking world of housework and childcare, women like Eliza Orr were keen to help the war effort. When a crisis in staffing meant the trams struggled to take the city to work, Eliza and others leapt at the chance to help.

Glasgow’s trams were losing staff rapidly as men joined up. Industry relied on people being able to travel. Cuts in tram services posed potentially serious problems for shipyards, factories and other employers. With the war effort depending on heavy industry, it was a problem Glasgow Corporation took very seriously. In spring 1915, it began recruiting women to work as conductors.

Women join the War Effort

Paid work done by women had traditionally fitted around childcare and domestic duties. But by 1915, there was no longer room for reluctance to employ women in roles away from the home. There were over 800 women conductors in the city by October 1915, and applications were arriving by the thousands. It was just as well – one year into the war, almost half the male staff on the trams had enlisted – 2,178 of 4,672. The women got the same pay as men, and same conditions. The tramways manager, James Dalrymple (…) was relieved at how “altogether satisfactory” the 818 women conductors were. They were “strong physically, and knew what it was to do a day’s work.”

Eliza was one of a family of 12 raised in the Gorbals. By 1915 she was married with two small children. Although she was expecting a third, she was keen to return to work. According to family recollections, she felt working on the trams was an important contribution to the war effort.

Despite Eliza’s long hours of housework, she took on work outside the home. There was no distinction between the working conditions of women and those of the men they replaced on the trams, with a 51-hour working week.

A wave of opportunity

In another experiment, Glasgow began trialling women as drivers, and Eliza became one in 1916. Eliza, who had a fourth child in 1918, went back to work as soon as she could. Family accounts recall her pride at being part of the wave of new opportunity for women that saw them given the vote (later) and have the chance to work outside the home.

‘Times they are a changin’

Both of these jobs resulted in changing perceptions, regarding the work women could do. Anyone who has read Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” (1813) will know that women were more or less barred from working life in 19th century Britain; this situation is similar to some backward societies in today’s world, such as Afghanistan. In other words, in Jane Austen’s world, middle class women were employed as nannies and private tutors, but were barred from many other professions, such as the legal and medical professions. But working class women were ‘allowed’ to work as prostitutes, or as ‘slave labour’ in the factories.