This post discusses the hereditary diseases of the Campbells and MacKinnons, as well as, that of the royal family.

Royalty and consanguineous ‘royal’ diseases

Consanguinity (inbreeding) often leads to hereditary diseases. Well known is that the British royal family have suffered from various inbred diseases. Queen Victoria of England (1837-1901) is believed to have been the carrier of haemophilia B. She passed the trait on to three of her nine children. Her son Leopold died of a haemorrhage after a fall when he was 30. Members of the Russian Romanov imperial family (related to the British royal family) also suffered from haemophilia. The presence of haemophilia B within the European royal families was well-known, with the condition once popularly known as “the royal disease”.

There was a reduction of the prevalence of haemophilia due to the efforts of ‘Doctor’ Vladimir Lenin. He ordered the euthanization of those members of the Russian royal family, who could be possible carriers of the recessive gene. More specifically, he issued an order to the government in Moscow to euthanize the Romanovs in order to improve the genetic pool of the Russian people.

The ‘Hapsburg Jaw’ and hereditary inbred diseases on Eigg

The “Habsburg jaw” has long been associated with inbreeding due to the high prevalence of consanguineous marriages in the Habsburg dynasty. It is perhaps widely believed that marriage between close relatives was rampant in remote Scottish regions, particularly the Highlands and Islands.

Within the confines of a small island such as Eigg, with a small population, the choice of spouse was limited. It was often a case of ‘marrying the girl next door’. It was literally true, regarding the marriage of my great grandparents, Roderick Campbell and Morag MacKinnon.

In fact, the blood lines of the Campbells and the MacKinnons seem to cross many times, although I haven’t conducted a thorough investigation. To what extent ‘inbreeding’ – marrying close relations – has been harmful in the islands of Scotland is beyond the scope of this book. So I will only make general observations, perhaps not always correct.

Hereditary “cleft lip”

As mentioned elsewhere here, Dugald and Ian MacKinnon had cleft lips. There is perhaps some evidence that clefts are more prevalent in intermarriage (consanguinity).

My mother had told me that John MacKinnon had a cleft palate. However, on reading Eigg – the Story of an Island (Dressler, 2007), she writes that Dugald MacKinnon was born with a cleft palate. So either my mother got the names mixed up or both John and Dugald had inherited this particular gene; but then they weren’t directly related. Although, as suggested elsewhere, they may have had a kin relation to the extended family. If one was to make a little witticism – in these small communities – ‘everyone’ was ‘related’. After all, we are all related to Adam and Eve!

As reported above regarding the deaths of some of Roderick Campbell’s children, the death certificates did not always state a cause of death, but a ‘supposed’ cause. Sarah MacKinnon (my great grandmother) died of ‘supposed paralysis eight years – not certified’. From a present day perspective, this seems absolutely unbelievable that she was paralysed for 8 years and had never received any medical attention! In other words, when my great-grandmother died of sickness in 1895, Eigg had no medical officer.

However, according to Dressler (2007: 127):

The Small Isles Parish Council for the Poor Law had finally appointed a medical officer in 1897, who was paid a yearly salary out of the rates collected in the four islands. (…) The nearest hospitals were in Glasgow, a ten-hour train journey away from Mallaig. (…) There was always a bed reserved for emergencies from Eigg (…) at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary (…).

Dugald MacKinnon certainly used that bed more than most as he had to undergo a series of operations for his cleft palate as a young child. He used to be left on his own. He was looked after by his brother Charlie, who was a tram driver in the city.

Dugald is fond of telling how he had woken up from one operation feeling ravenously hungry. Seeing the food trolley wheeled past him, he got out of bed, grabbed a plate of fish and mashed potatoes. He wolfed it down, ignoring the nurses’ warnings which he could not understand, having little English at the time.

The result was burst stitches and a frantic phone-call to his brother at 5 ‘o’ clock in the morning when everyone thought he was going to die. This was counting without Dugald’s remarkable stamina. Joking about being the family weakling that survived all his siblings, Dugald recently celebrated his golden wedding anniversary, surrounded by numerous grandchildren and friends.

Hereditary diseases of the Campbells and MacKinnons

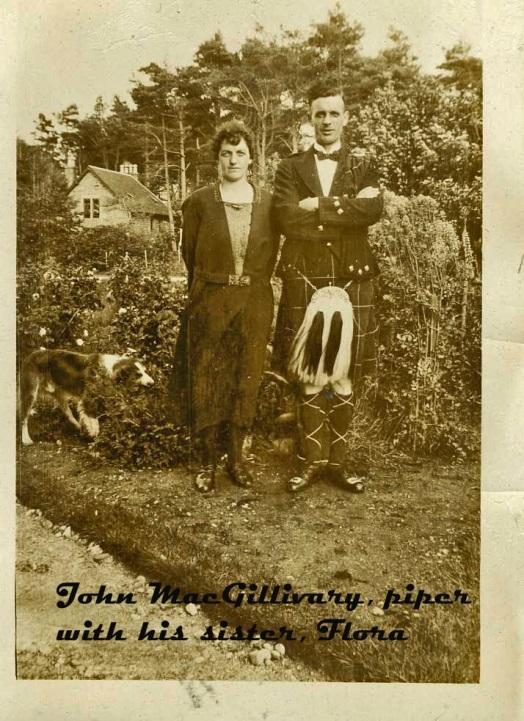

Roderick Campbell, used to carry his wife around the island for many of the last years of her life. She suffered from ‘paralysis’, but this diagnosis was never made more precise. My grandmother, Morag MacGillivray, suffered from multiple sclerosis. According to my cousin, Dawn Driscoll, she said that her father (Donald) had remembered his dad carrying his mum around. This was perhaps before she got a wheelchair. The photo here shows her in a wheelchair (perhaps taken sometime around 1950).

Despite being sick, she managed to put a good face on things. One might imagine that Morag inherited the disease from her mother. But there doesn’t seem to be any scientific evidence that can confirm this. Moreover, we don’t know the exact specifics of my great grandmother’s sickness. Death certificates in the late nineteenth century were often very vague as regarding the cause of death.