This is not primarily a historical or sociological narrative, but I’d like to discuss the culture of infanticide and baby farming in the past. However, it is impossible to gloss over certain facts. Victorian Britain was characterized by misogynist and classist laws and culture.

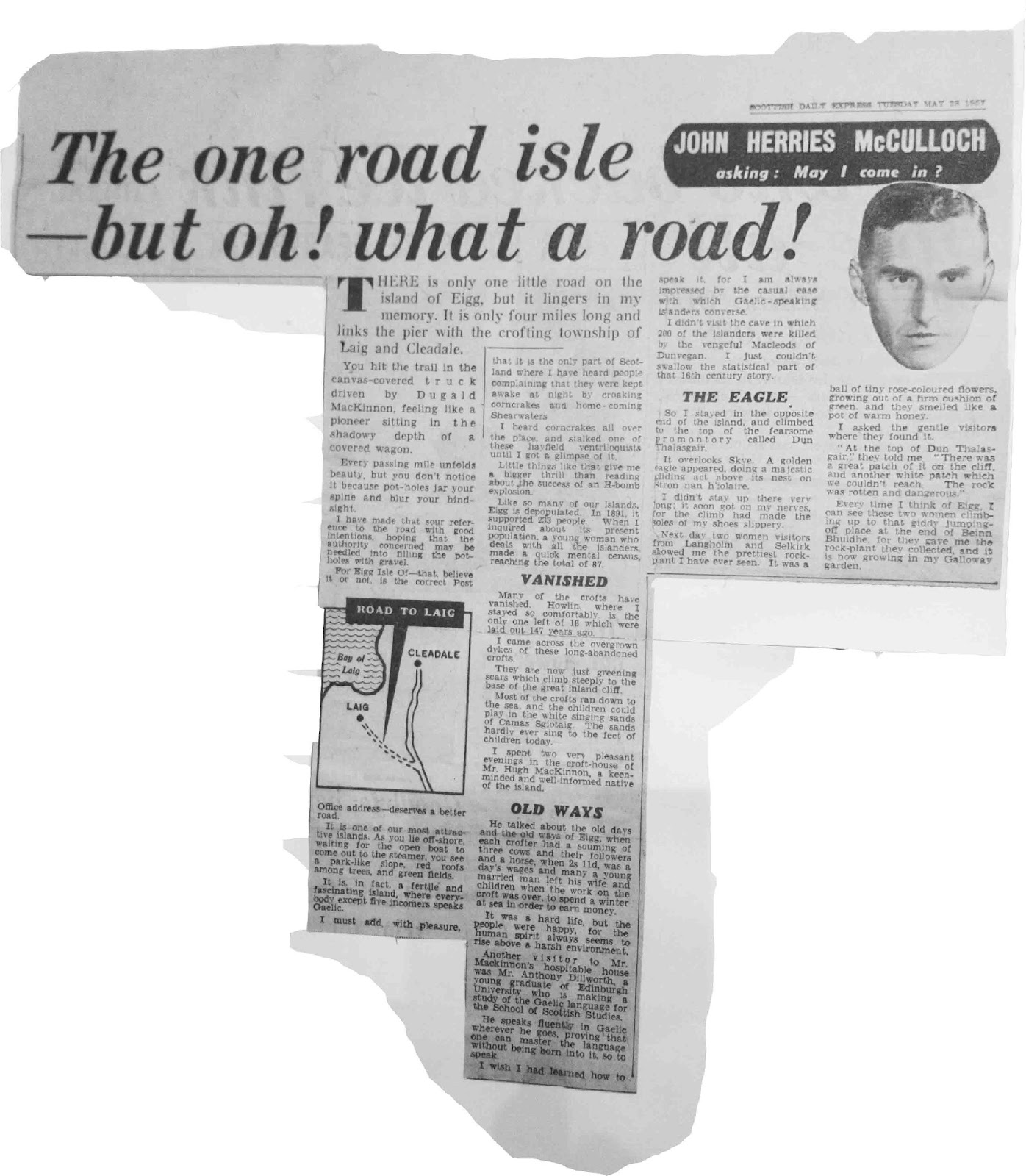

I have already briefly mentioned the Anglo-centrism of the authorities with regard to the refusal to use Gaelic names on official documents. The Gaelic people of the Western Islands were also subjected to ‘classism’. Here, prejudice and aggressive actions aimed at what is deemed to be people of a lower class, such as exemplified by the Highland clearances.

Infanticide on Kildonnan Beach 1880

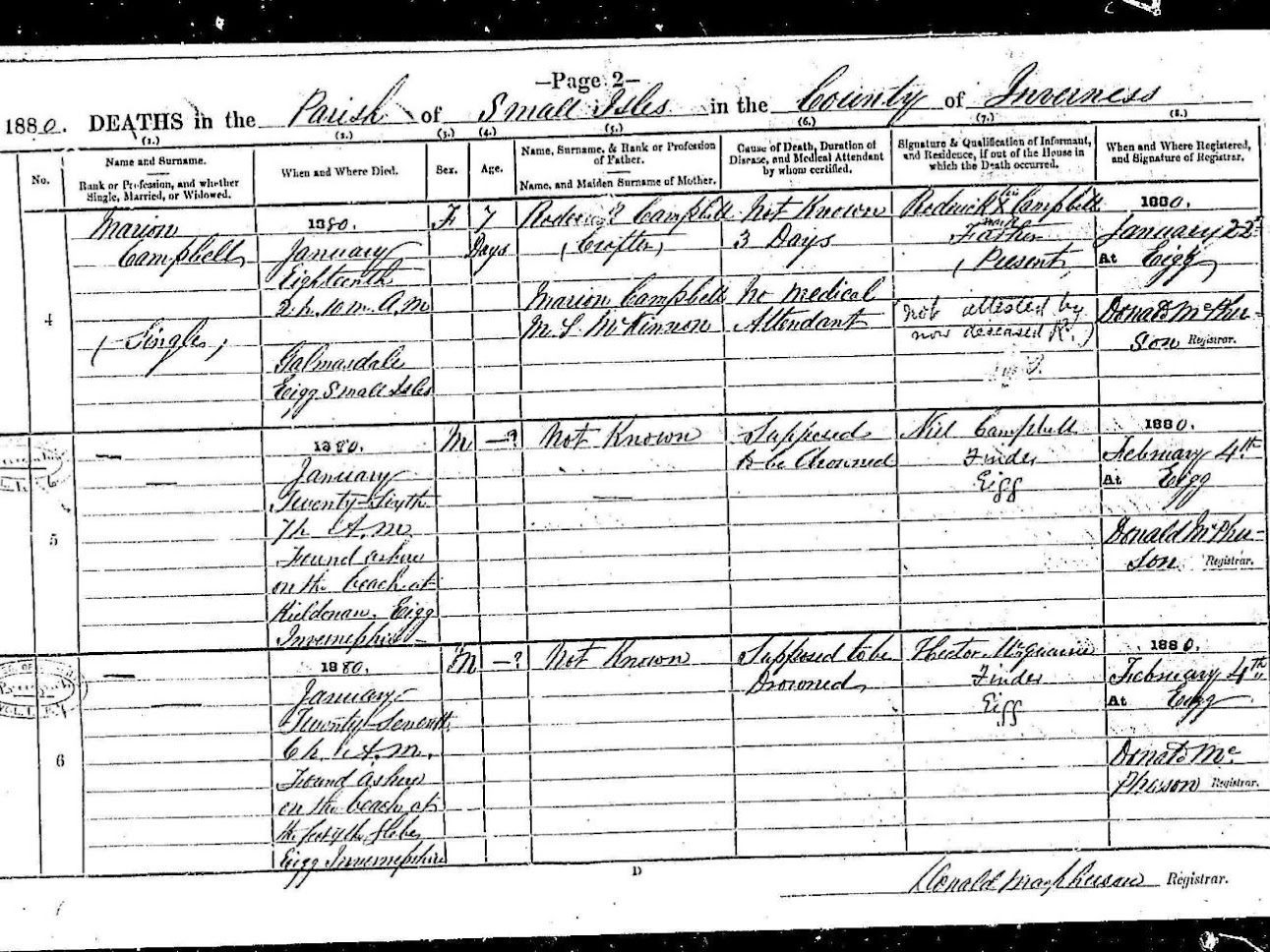

The certificate shows the death of two children with no name and no age. What is more surprising is that these two children are ‘found’ by two different people at two different places (on the beach). The cause of death for one of the children is given as “supposed to be drowned”; the writing for the cause of death for the other child is difficult to read. I say ‘child’ – one assumes it is a baby as no age is given.

In Victorian Britain, “illegitimacy involved loss of social status and marriage prospects”. In many cases was the cause, directly or indirectly, of infanticide.

To return to the two dead babies found on the beaches of Eigg in 1880, there is something more than tragic about such deaths. The babies have not only been discarded; their abandonment is made all the more evident by the visual image of them being offered up to the brutal forces of nature.

The dead babies on the beaches of Eigg were not given any visual representation apart from the official records. Neither did the Isle of Eigg have policemen who could investigate such matters. In other words, they were quickly forgotten, until I ‘unearthed’ their death certificates some 140 years later. Of course, this is a ‘cold case’ that will never be investigated further.

I mention all this here because ‘dead babies on the beach’ today is something that awakens people’s empathy (perhaps temporarily), due to the viral global posting of images. In particular, I am referring to the death of a two-year-old Syrian boy found on a Libyan beach in 2015. But out of respect for the family I won’t say more on this subject here.

The above description of the ‘dead babies on the beach’ forms the basis for a semi-fictional story, “Siobhan’s Baby”.

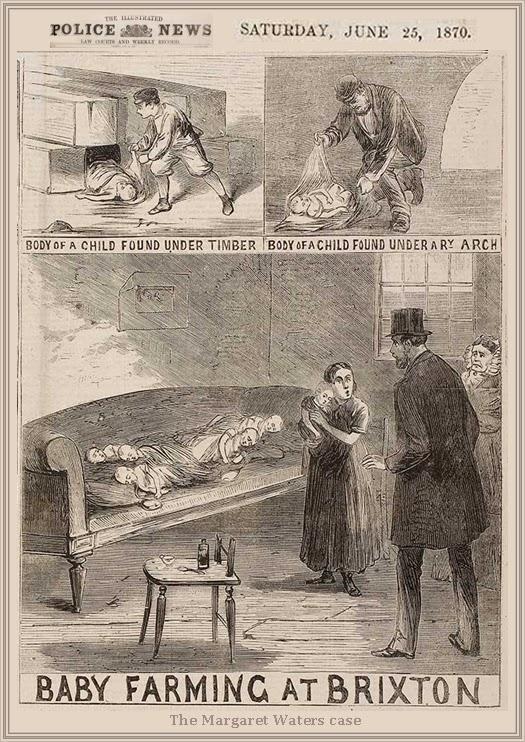

Baby Farming in the 19th Century

The death of the children shown in the death certificate of Marion above could, of course, have been an accident; but as they are not identified by name and age, one is tempted to assume that they were killed in some way. It is also possible that their deaths didn’t want to be acknowledged by the mother or father for whatever reason.

If they had no name or age, this means that they had not been registered at birth. The finding of two children by two different people on two different beaches might also seems to suggest they had been subjected to ‘baby farming’. Such was widespread in Victorian Britain. One can also ask the question, for these two babies that were found, how many more were lost in the waves? This seems to suggest some kind of epidemic, which is seldom ‘talked about’. In other words, the death certificates of these two babies is perhaps just the tip of the iceberg.

Baby farming is the historical practice of accepting custody of a child in exchange for payment in late-Victorian Britain. Dorothy L. Haller explains in her article “Bastardy and Baby Farming in Victorian England” (1989-90). Baby farmers, on the pretense of looking after an unwanted child, would actually starve the child to death. They would then feed it with poison or smother the child in their care. They’d then dump the body in the river or on the street wrapped in rags or newspaper; or, in our case, throw them in the sea or leave them on the beach.

The Victorian ideal of the sanctity of the family resulted indirectly and directly in endangering the lives of children born of poor unmarried women. This religious and ideological ideal of the sanctity of marriage also prevented the establishment of adequate laws to protect these children (Haller, 1989-90). The reform of the Bastardy Laws in 1872 were amended, making the father equally liable for the support of his illegitimate child. It also enabled the mothers to obtain support for their children.

Baby farming, English literature, and ‘She-butchers’

When one reads Victorian or pre-Victorian literature, one often has to learn to read between the lines. Some of the novels of Daniel Defoe are about the lives of prostitutes in the 18th century, such as “Roxana” and “Moll Flanders”. When I read these novels, the idea of ‘baby farming’ was something that never crossed my mind. But in the novels, many of the children of the anti-heroines are ‘given away’ to others for a small fee. In fact, Moll was herself brought up in a foster family.

Defoe was very much a social realist who didn’t so much sentimentalize the stories of the oppressed, but scandalized them. In other words, I realise in retrospect that Defoe was describing ‘baby farming’:

“This is the main affliction in other cases, where there is not substance sufficient without breaking into the fortunes of the family. In those cases, either a man’s legitimate children suffer, which is very unnatural, or the unfortunate mother of that illegitimate birth has a dreadful affliction; either of being turned off with her child, and be left to starve, etc., or of seeing the poor infant packed off with a piece of money to those she-butchers who take children off their hands. As ’tis called, that is to say, starve them, and, in a word, murder them.” (“The Life of Roxana”).

As mentioned above, Marion McKinnon was illegitimate, and lived with her grandparents. Marion’s birth certificate (1855) states that Hugh MacKinnon is the father; but 1855 was 17 years before the law of 1872, referred to above. So it is doubtful that Hugh McKinnon provided any financial support for his child. Marion was thus ‘farmed out’ to the grandparents who, thankfully, were not like the murderous baby farmers described in Haller’s article.

The primary objective of professional baby farmers was to solicit as many sickly infants or infants under two months as possible. Life was precarious for them and their deaths would appear more natural. They would adopt the infants for a set fee and get rid of them as quickly as possible in order to maximize their profits.

The infants were kept drugged on laudanum, paregoric, and other poisons, and fed watered down milk laced with lime. They quickly died of thrush induced by malnutrition and fluid on the brain due to excessive doses of strong narcotics. The costs of burial was avoided by wrapping the naked bodies of the dead infants in old newspapers and dumping them in a deserted area; in other instances, by throwing them in the Thames.

In other words, if Morag (Marion) had been farmed out to others, I most probably wouldn’t be here to write this account! The islanders obviously couldn’t throw their unwanted babies in the Thames; but they were surrounded on all sides by the gaping mouth of the ocean. It might be imagined that the babies were left on the beach. More probable is the possibility that they were thrown from a boat. But the ocean, refusing to swallow such unhallowed food, spewed them up on the beach.

The fact that Marion’s second born, and the two dead children on the beach, also ended up on the same death certificate also seems to have some portentous significance.

As mentioned, Marion McKinnon lived with her grandparents, and not with her mother (see censuses 1861-1881). The 1871 census also shows two other grandchildren living with them, John and Alexander Halladay. In other words, the documents from ScotlandsPeople provide a lot of information. But there are also many loose ends: Where was Mary McKay (Marion’s mother) living? Who was Hugh McKinnon’s wife? Where was the father of the two Halladay children?

This was perhaps James Halladay who fathered Donald Halladay in 1859. He lived in Galmisdale married to Ann Halladay (nee McKay). However, there is a limit to how much time one can spend researching these matters. It also often leads to more unanswered questions – a real jigsaw puzzle! Besides, ScotlandsPeople is not likely to disappear in the near future, making further research possible.

Illegitimacy and infanticide in Victorian Britain

The combination of a number of factors in Victorian Britain led to high rates of infanticide. There was perhaps no single cause for this high rate of infanticide. It may have been a combination of factors such as Victorian ideas concerning the sanctity of marriage.

There’s also a lack of governmental legislation protecting illegitimate children. In fact, the existing legislation was one of the causes of the abuse and murder of children born out of wedlock. There’s also lack of legislation protecting unmarried mothers. The existing legislation was abusive towards women). However, these somewhat abstract factors tend to mist over understanding rather than illuminating issues. It is perhaps better to let the stories tell themselves.

The Case of the Missing Baby

Elizabeth Ritchie’s article “The Case of the Missing Baby: Illegitimacy and Infanticide in the Islands” (2008) provides a good description of infanticide in the Western Isles during this period.

In 1832, Margaret MacDonald was 23 and living with her parents on the farm of Tigharry, North Uist. Her father was a tenant farmer. (…) That spring a liaison with Alexander MacDonald left her pregnant. In a panic-stricken quandary, Margaret laid plans with her fifteen year old niece to leave the island. It was perhaps to escape family disapproval or church discipline. Kirk Session records for North Uist no longer exist; but the cases of 40 illegitimate children in the 1830s were attended to in a neighbouring parish.

Offenders were reprimanded but the chief function of prosecutions was to enforce paternal support for mother and child. Such community censure was part of the system for sexual regulation and community incorporation of the children. Illegitimacy was therefore far from unknown, but still involved loss of social status and marriage prospects. Fear of the response to her pregnancy drove Margaret to escape the island for a while.

For 7 weeks, the women lived on Eigg with a cousin, then moved to Arisaig for two weeks, staying with a cottar family. Under questioning from the cottar’s wife, Margaret created her cover story. She was married to a North Uist man and was returning home for her confinement, delaying because she felt unwell. They sailed to Skye and walked through the parish of Sleat, staying with families for three weeks. In Broadford she went into labour and was assisted by the miller’s wife.

Margaret was unsure whether or not it was a premature birth, being “quite ignorant of the length of time in which a woman goes with child.” She worried her daughter was not healthy as she was always crying, but a local man disagreed and added Margaret seemed fond of the girl, nursing her and feeding her porridge gruel, fearing she had insufficient milk.

One day as they trekked towards Dunvegan port, rain made them seek shelter. As it cleared up and the child was asleep and warm, they carried on. To her horror, when Margaret next checked the baby, she was dead. The child had refused to feed all day so may have been weakened, or ailing and unable to contend with the January climate.

A study of infanticide in Shetland suggests baby deaths usually occurred because of motherly neglect rather than being premeditated; yet in Galloway brutality appeared common. Margaret falls into neither category easily, seeming to care for the baby yet lacking knowledge. Having removed herself from the guidance and support of the female community in North Uist, the baby was at the mercy of her mother’s ignorance.

Alone, and with a body on their hands, the girls sat behind some peat stacks by the road and cried. They buried the baby in a ruinous hut “loosly covered over with turf … wrapped in a checked apron”. Over a week after their return home they confessed to Margaret’s sister. Her brother John was sent to disinter the body and Margaret was accused of child murder. Several Skye men helped John dig up the corpse, which smelled too badly, to ascertain whether the child had been injured. She was buried at Bracadale, Skye.

Had she been accused fifty years previously, Margaret would probably have hanged. Instead she benefited from an 1809 legal change which required proof of three things: that pregnancy was concealed, no help was called for at the birth, and that there was no living child. The birthing assistance of the Broadford miller’s wife may therefore have saved her. Margaret escaped the noose; although how the episode and the subsequent notoriety affected the rest of her life, we are left in ignorance.

This is just one of hundreds, or perhaps thousands, of such stories about illegitimacy and infanticide in Victorian Britain.

“Infanticide in 19th Century England”

The following summary of an article, “Infanticide in 19th Century England” (2017) by Nicolá Goc also deals with the same topic.

In February 1829, Harriet Farrell, aged seventeen, found herself on trial in the Old Bailey (the central criminal court of London). She was charged with “the wilful murder of her bastard child.” Harriet was a servant, in the household of Jonathan Cook, a “trunk-maker.” Cook’s wife had asked her repeatedly if she was in the “family way”; but Harriet had always denied it. She denied giving birth, too; but the Cooks were suspicious, and they found the body of a baby in the privy.

At this point, Harriet ended up in the hands of the law, charged with murder. But when she was tried in the Old Bailey, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. They did find Harriet guilty of a lesser crime, concealing the birth of a child. She was sentenced to a year in prison.

Shearwater Tradition

When I visited Eigg in the summer of 2007, I met Duncan Ferguson who is interested in local history. I mentioned my ‘great uncle’ Hugh Campbell who had died at the age of six from falling off a cliff in 1890. I asked him if children might be involved in work activities; that is, be a part of the family’s economic unit (what today would constitute illegal child labour). It had struck me that the cliff was some distance from the Galmisdale cottage, at least for a 6 year old boy. I was perhaps looking at this from the perspective of a so-called ‘modern’ parent. My son was eight year’s old at the time.

Duncan said, “Undoubtedly, the Eigg people were known as the fachach (Gaelic for Manx shearwaters). They collected eggs and killed the young of the Shearwater birds; and this was an important source of food for families, part of their livelihood.” He also pointed out that Craignafeulac, where Hugh fell from the cliffs, was near the Cathedral Cave. It was perhaps not that far from Galmisdale.

The shearwater hunting tradition is described in detail in Camille Dressler’s book, Eigg – The Story of an Island (2007). It explains that the tradition stretches as far back as to 1545 (as reported by Dean Munro), and endured into the 1930s.

The islanders climbed the cliffs to catch the handsome black-and-white birds. Since time immemorial, they have laid their single eggs in burrows at the top of the Cleadale cliffs. Eigg people used to catch both adults and the young bird. They became so fat from their nightly feedings that the shearwater’s name on the island was fachach, fatling. They were either boiled or salted down for later use.

The islanders were so partial to their taste, less oily than the cormorant or shags and more like veal, that in time the name fachach became the islanders’ soubriquet. They did not mind it; on the contrary, they took a certain pride in it. They said that no islander was a true Eiggach who had not eaten a fachach (Dressler, 2007: 30).

(…)

There was also the shearwater hunt in late July or early August, a tradition which endured until the 1930s. During his visit to the island in 1926, the naturalist Charles Connel had been able to record that ‘there was an unwritten law which forbade the islanders to approach the nests of the Manx shearwaters, nesting then on the cliff tops and accessible gullies of Beinn Bhuide, as well as the sides where they nest today, until an appointed day. Then, the whole island, young and old, set to work to scour the dizzy and treacherous cliffs; and in a single day, they cleared the accessible portions of their living food store.’

According to Dodie Campbell, who went hunting for shearwaters with his own father, the oily fachach – the young shearwater – was so fat that ‘you could just squeeze it and the oil would pour out of its beak. It was great for waterproofing your shoes’, he added with a satisfied grin at the horrified gasp which generally greeted that anecdote” (Dressler, 2007: 112-113).

In other words, this description of the shearwater hunt in late July or early August coincides with the date of Hugh Campbell’s death from falling off a cliff on July 20th. It seems likely that 6-year-old Hugh Campbell fell to his death while participating in the Shearwater Hunt. Viewed from a modern perspective, it might be said that he died in an industrial accident, and an illegal one at that.

Ignoring the historical perspective, it is nevertheless harsh in human terms to risk the lives of your own children in the desperate search for food amongst the cliffs. However, it is difficult to be judgemental. According to Connell and Dean Munro this was a centuries old tradition which all the islanders participated in.

Perhaps this was an ‘isolated’ accident, and parents were watchful of their children. In this context, the word ‘parents’ is also important. Hugh’s mother in 1890 had been suffering from ‘paralysis’ at the time, although only 34 years old. Fathers would traditionally not be involved in the constant watch over their children. It seems likely that Flora Campbell (59 years old), Roderick’s sister, probably had an important maternal function in the family household. In fact, she would probably have functioned as the family’s ‘mother’ after the death of Morag in 1895.

My grandmother, Morag, was only 3 years old when her mother died. Her auntie was most likely the ‘mother’ in her family who she would have related to. This ‘spinster’ most likely had an invaluable role in the family. She lived with her brother until she died when she had reached 80 years old in 1910. By this time the youngest living child of the family was Morag who would have been ‘grown up’ – 18 years old. In other words, we may assume that Auntie Flora had her work cut out bringing up her brother’s children.

We can also assume that the adults were not always that ‘watchful’ of the children. The children were probably allowed, or even encouraged, to roam free. Of course, this whole supposition is based on official documents; it was not anything which I have heard from anyone in the family. Such stories are probably all now forgotten, and only the official records remain to tell their tale. However, they are also presented here, as told to me by my mother!

I feel tempted to include a slight digression here. My grandmother, Morag, never had a mother as such. What’s more, one might imagine that her father, and her Aunt Flora, might have felt the necessity to be strict, and use the tawse to keep their children under control. This partly might explain my mother’s complaint that her mother was by no means an ‘ideal’ mother; and that she often resorted to the tawse.

Both my mother and Katie MacKinnon talked about the children ‘running free’ on the island. Not least, my mother followed this policy when bringing up her own children. When we were living in England, she let us play in the surrounding countryside, far away from the house.

I have assumed here that Hugh was part of an organized hunt. But taking into account the lack of parental supervision, he might have been hunting for eggs and birds together with other children. This hypothesis seems to be supported by Hugh Miller’s description of the shearwater hunting in his book, The Cruise of the Betsey (1858).

In former times the puffin (shearwater) furnished the people of Eigg with a staple article of food; and the people of Eigg, taught by their necessities, were bold cragsmen. But men do not peril life and limb for the mere sake of a meal, save when they cannot help it; and the introduction of the potato has done much to put out the practice of climbing for the bird, except among a few young lads, who find excitement enough in the work to pursue it for its own sake, as an amusement.

Miller seems to contradict Camille Dressler’s description of the Shearwater Hunt being a yearly tradition. However, what he does point out though is that “young lads, who find excitement enough in the work to pursue it for its own sake, as an amusement“. In other words, this was something children did for ‘fun’; suggesting that Hugh might have been doing it together with other ‘lads’ when he fell off the cliff.

On the other hand, as cited above, Charles Connel pointed out “that the whole island, young and old, set to work to scour the dizzy and treacherous cliffs“. It is well known that in the 19th century, the British state allowed children as young as five years old to work in mines. In fact, it was deemed an advantage being young and small of stature. Young children were able to crawl through narrow shafts not accessible to an adult.

Similarly, the smallness, dexterity, and fearlessness of young children qualified them well for climbing treacherous crags and moving along narrow cliff ledges where the birds laid their eggs. To add a cynical comment, one might say this was a win-win situation for parents and adults. If the child was able to find the eggs and small birds, they would in effect be paying for their own upkeep. If they fell off the cliff, it would mean one mouth less to feed.