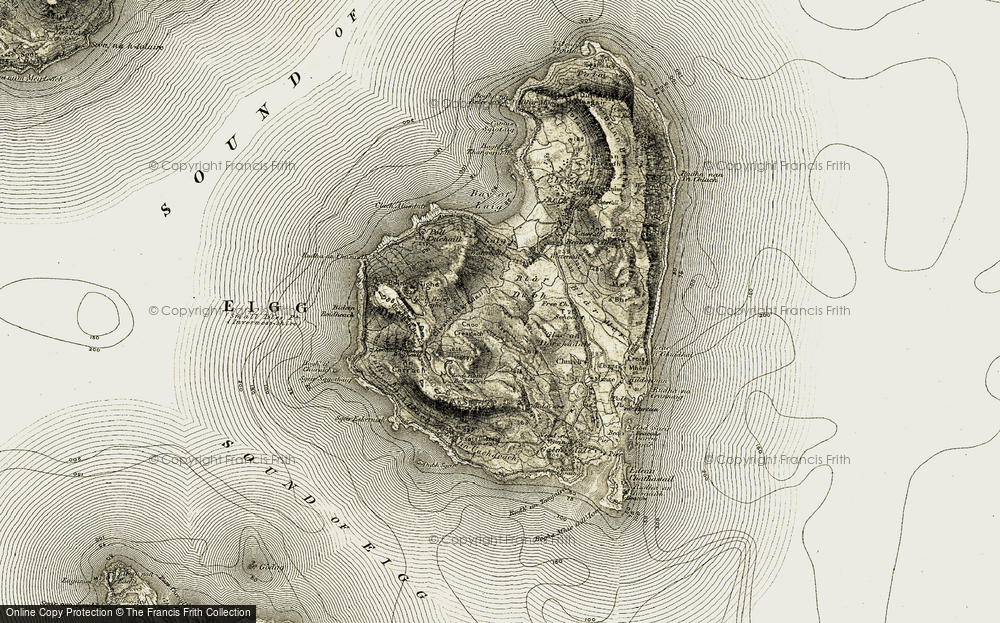

Eigg and its People is not primarily a historical or sociological narrative, but the history of one family on the Isle of Eigg. However, by focusing on one family who still have some descendants living on the island. This documents to some extent the cultural genocide, or the disappearance of people, language, and culture of the Isle of Eigg.

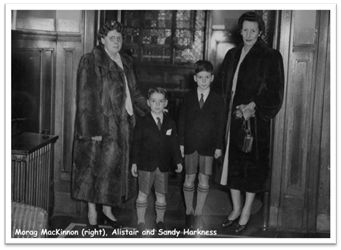

This disappearance is evidenced by the fact that there are very few people left on the island who speak Gaelic as their mother tongue; Katie MacKinnon (she was in her eighties around 2007) being one of them. Katie is my mother’s cousin, and the daughter of Flora McKinnon, the daughter of Roderick and Morag Campbell. The Gaelic language and culture, which persisted up until the post WWII period has its roots in the pre-historic past. My grandmother, Morag Campbell, spoke Gaelic as her mother tongue.

Katie MacKinnon says that my mother understood Gaelic, but she could not speak Gaelic. It seems likely as she visited the island every summer where the children and adults spoke Gaelic. Her mother would also obviously speak Gaelic when she visited the island. However, my mother seems to have ‘forgotten’ her Gaelic after some years. I never heard my mother speak a word of Gaelic, except when she uttered the MacGillivary war cry, “Dunmaglas”. (‘Touch not this cat without a glove’).

I think my mother in some roundabout way connected this idea to the wild cats of Scotland. In fact, she even claimed that one of her “Poppy cats” (they were all named Poppy) was blood related to a Scottish wild cat. It was also possibly blood related to the pets of the Jacobite rebels. This is perhaps not as absurd as it seems. The wildcat is considered an icon of the Scottish wilderness. It has been used in clan heraldry since the 13th century.

Ironically, the official records such as the census records, births, deaths and marriages provide much of the concrete evidence of how these people lived. Being written in English, it also represents a process of Anglicisation; this process is evident in the 1891 census which provides information concerning the languages spoken by the inhabitants.

The various censuses show, generally, that some children spoke only Gaelic before attending school. Gaelic was spoken by more or less all of the older people. On the whole, schoolchildren and younger inhabitants spoke both Gaelic and English. However, there seem to be none or few who spoke only English. Of course, the opposite is the case today.

This question, regarding economic and population trends, is answered in part in Eigg – An Island Landscape by Susanna Wade Martins (2004). However, economic and population trends are often ‘faceless’; i.e. ‘interest’ is provided when names, faces, and personal accounts can be combined with historic trends and factual details. Oral accounts are also of interest, but they can become intermingled with myth.

It is of interest to back up ‘myth and legend’ with hard evidence, such as my mother’s/grandmother’s anecdote concerning my grandmother’s brother, Hugh Campbell. He died falling off a cliff searching for shearwaters when he was only six years old in 1890. It is also of interest to attempt to paint in some detail of the lives of some of the individuals who are, on the whole, almost completely forgotten, or at least only remembered in fragmented accounts and anecdotes. This book hopes to breathe life into the likes of Hugh and others by recording in writing about the few details we have about their lives.