In Rhoda’s 1962 Diary, my mother talks about her household activities, social activities, and all the different roles she plays during our childhood.

“Household chores; Sunday dinner; mending and ironing clothes.”

The architect of festivities

Of course, everyone has an ‘apple-pie mother’, someone who bakes apple pies better than any other mother! But my mother had outstanding qualifications. She was a young woman during the war years and was in charge of various ‘victory gardens’, not to mention other ‘domestic industries’.

There is a great paradox here called the ‘Thucydides Trap’. This concept refers to the inevitable conflict between a dominant power and a rising power (Allison, 2018; Thucydides, 2009), much like World War Two. The paradox is that Britain tried to hinder the innovative developments and economies of Germany and Japan, and was forced to retreat to pre-industrial activities, such as domestic industries, i.e., ‘victory vegetable gardens’. However, in this retroactive process, my mother learned many new skills. Ironically these have also become a trend again due to climate change fears.

One of the first ‘environmentalists’

My mother didn’t like lesbians, feminists, communists, miners, Australians, the Welsh, the English, the Americans, the hippies, the ‘Greens’, the ‘lefties’, the blondes, the working class, the Russians, the Germans, the Irish; the list is too long to include all her ‘hate objects’ here.

Of course, my mother was no worse or better than other right-wing xenophobic and homophobic readers of the right-wing gutter-trash media, such as the “The Daily Express” and “The Daily Telegraph”. But I mention this list here because she was an unintentional ‘Green’, in that she believed in self-sustainability.

In other words, without knowing it, she was one of the people she didn’t like! She was assisted in this ‘green’ project by my ‘green’ father. They both contributed in their various ways to reducing the family’s ‘carbon footprint’.

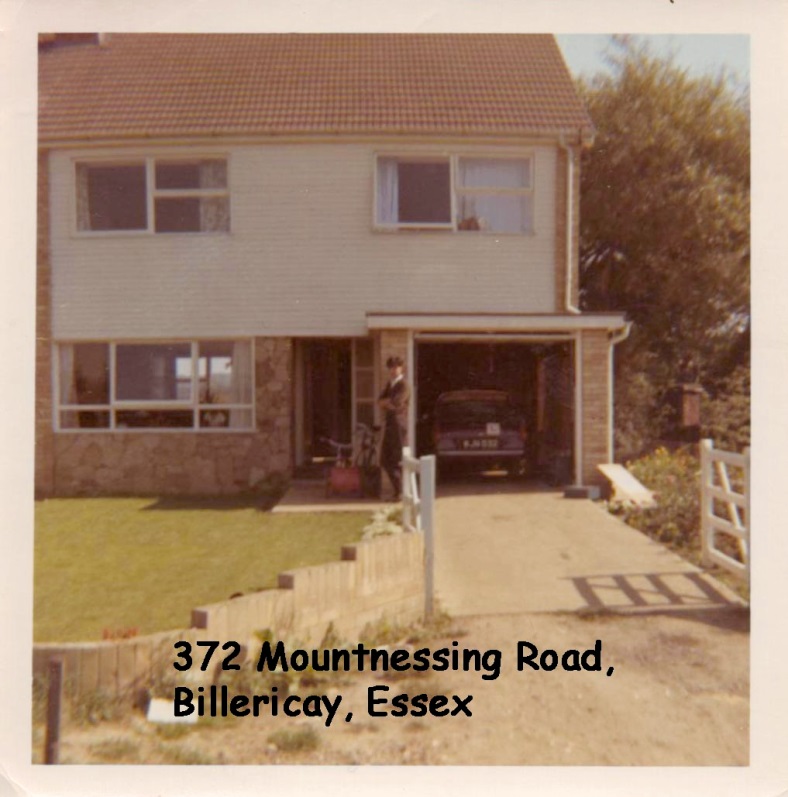

My father believed in using local ‘resources’, and relying on his own initiative and activities. He was a ‘house builder’: he built the ‘double’ car garage for our house in Billericay, Essex; a ‘plumber’: he installed the central heating in the Billericay house. He was a ‘car mechanic’: repaired numerous family cars and motor bikes, such as the Wolseley 12 and Ford Anglia, and my BSA 650cc Golden Flash.

He was a ‘gardener’: he maintained the gardens in our various houses; an ‘interior decorator’: he did the carpeting, wallpapering, painting, and so on, in our various houses; he was a ‘boat builder’: he helped build my canoe for my Gold Duke of Edinburgh Award; he was a ‘repairman’: he repaired various domestic appliances, such as washing machines. This list would be too long, if I were to include everything!

My mother’s domestic production

My mother was an expert at budgeting (sustainable economics), and all kinds of domestic production. She liked making apple pies, Eccles cakes, rhubarb pies, jams, and so on (in other words, domestic production with a low carbon footprint).

Like many other ‘housewives’ of the period, my mother had a Singer sewing machine. The Singer sewing machine was a ‘work of art’ with an exquisite design encased in a walnut case! Of course, this is another example of advanced American technology at the time, as the Singer Corporation is an American manufacturer. Like many other ‘great’ Americans, Isaac Singer was born to German-Jewish immigrants.

Of course, this is a retrospective view; it never entered my 12-year-old boyish mind that the Singer sewing machine was a ‘work of art’ with its exquisite design.

What I liked about the machine was the fact that it was like an Elon Musk EV in embryonic form. In other words, it had an electric engine and an accelerator pedal! Ok, this analogy is somewhat exaggerated because Musk’s cars sound more like milk floats than sewing machines.

When you pressed down the accelerator pedal of the Singer it made a clattering racket. It was like a tin-can full of nails being spun in a high-speed dryer! My mother would even let me ‘drive’ the ‘mean machine’ sometimes. In my boyish imagination, I imagined that I was driving a high-speed car!

In the period of rationing during and after the war, clothes were rationed. My mother had to make many of her children’s clothes; as seen in the photo of my three elder brothers in front of my father’s ‘Flying Standard’, taken around the late 1940s or early 1950s; they are wearing ‘home-made’ trousers and shirts.

As you can see from the photo, my mother was no ‘Saville Row’ tailor, although she did her best! In other words, the photo shows that my brothers’ short trousers were obviously ‘home-made’.

Today, you can buy cheap Ikea curtains already cut and ‘hemmed’. But in the ‘old days’, this was a ‘major’ job; you had to buy the material, cut it to the exact dimensions, and sew ‘the hems’ and the inserts for the curtain rods. So this was something else my mother also did with her sewing machine.

But returning to the point above, my mother received little thanks from her children for all her ‘domestic’ efforts, as this was something they took for granted!

Housewives: unpaid workers and slaves

Despite all the work my mother did in the home, not to mention her budgeting work, she was one of the millions of unpaid female workers (‘slaves’) in post-war Britain, or the rest of the world for that matter.

In other words, my mother was not only little appreciated by her children, but also an unpaid servant! This was a matter of adding insult to injury! Of course, I don’t intend to enter into a socio-economic essay on this topic here; but it is something that can’t be sidestepped, at least not without a brief comment.

Thus, the work of housewives was not included in GDP calculations, nor fully included in other calculations, such as welfare, unemployment and pension benefits. This often resulted in dire consequences for many women; they often outlived their husbands, thus had to subsist on a basic minimum pension, despite working hard all their lives.

My mother as ‘the boss’

Despite not being ‘recognized’ as a ‘worker’ and fully participating member of the British economy, my mother was, nevertheless, ‘the boss’ within a family context. She was the ‘boss’ in more ways than one. She had responsibility for the family’s finances.

I think my Uncle Alec wrote in a wartime letter that he never expected my father would end up ‘henpecked’ or ‘tied to his wife’s apron strings’. But perhaps Uncle Alec misses the point. It was no easy job taking care of the family budget. If left up to my father, he would have probably spent his money on cigarettes and whisky (as commented on by my mother in one of the wartime letters) or other ‘manly’ things, such as cars.

In fact, in one of the conversations with my mother, I asked her why my father lost contact with his relatives in Edinburgh. She replied that he had ‘squandered’ some of his mother’s inheritance (1934) by purchasing a motorbike. This event soured relations with his wider family. Although he still had contact with his granny, Isabella, in the 1940s (evident from the ‘wartime letters’).

I never saw any pictures of this ‘motorbike’, and my father never mentioned it. His enthusiasm to help me repair my 1954 BSA Golden Flash suggests that this brought back old boyhood memories for him. But my father was a man of few words when talking to his children, so he never told me he had a motorbike in the 1930s. In summary, my mother probably also thought my father was impractical regarding personal finances.

Household accountant

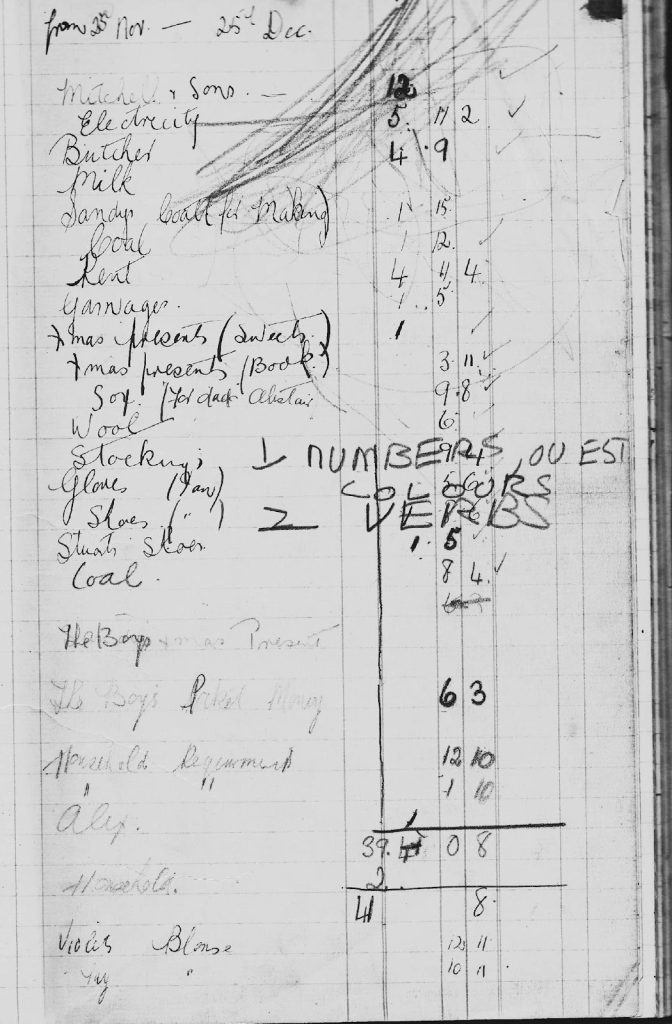

I happen to have two old ‘accounts books’, which my father probably filched from his government employer, as I couldn’t imagine this is something my parents would buy, as they are leather-bound, and were probably quite expensive.

The accounts seem to be from 1952 and later; that is, ten years before the “Diary” was written. My mother seems to have grown tired of using these books just for accounts, so they were later used as scrapbooks by her and us kids.

Thus, using the accounts books as scrapbooks, my mother wrote about the island where her mother was born, the Isle of Eigg, in the Western Isles. She writes about the massacre of our people by the cowardly MacLeods (as mentioned above). In other words, we kids and my mother used the scrapbooks for stories, drawings, homework (science experiments), games (which we invented), and many other things.

I won’t scan all the pages of the books, but I can briefly refer to one of the pages regarding accounts, or more precisely, ‘housekeeping’, as a point of illustration:

She mentions ‘coal’ £1 12 shillings (most British houses had coal fires). She then mentions ‘rent’, which is £4 4 shillings and 4 pence. This must have been when we were living at Bowfell Road, Mirehouse, Cumberland. In other words, they hadn’t yet bought a house.

She then mentions ‘book’ (Xmas present): 3 shillings 11 pence. She also mentions ‘wool’; in other words, she is making clothes for herself or her family. She then goes on to mention ‘pocket money’ – the boys’ 6 shillings and 3 pence. And then she amusingly writes, “Alex £1”, which suggests she had total control of his wages. So perhaps he was ‘given’ £1 for petrol and cigarettes?

I have only commented on some of the items.