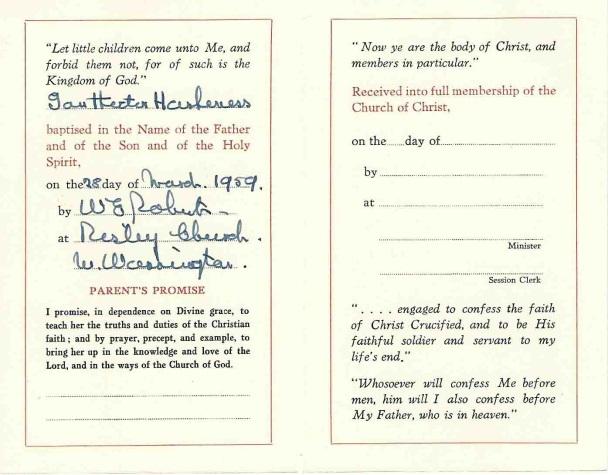

My brothers and I were all baptised at 26 Hob Hey Lane, Culcheth, 28 March 1959, by the vicar W. E. Roberts. It was a pretty simple affair; we were all standing in line in the smallish furniture-cluttered sitting room next to the Ferguson radiogramme. The baptism was over before you realised it had begun. The only person who seemed to notice anything out of the ordinary was my baby brother Gavin who started to cry, objecting to water being sprinkled on him by Mr. Roberts. I must have been about 10 years old, while Gavin was only a few months. It was fairly dreary and without ceremony– typical of Presbyterian Church traditions. However, this had not set my religious beliefs in stone.

On going through my mother’s documents some years after her death I discovered the ‘Certificates of Baptism’ for myself and three of my brothers, Gavin, Alistair and Stuart. My eldest brother Alexander’s wasn’t – perhaps he wasn’t there?

The bapitsam certificate is a kind of promise by the baptised to follow the Christian faith; it also includes a so-called ‘Parent’s Promise’ “to teach the truths of the Christian faith to the child. Yet our mother never showed us these certificates.

W. E. Roberts, the Minister of the Chapel

The Risley Chapel and Sunday School I mentioned previously was Presbyterian church. The minister was called Mr. Roberts, a Welshman of medium height. My child’s memory remembers mainly that he had white hair and a large red nose. He used to stand outside the church door on Sundays and smilingly greet people as they arrived. Mr. Roberts was a prominent figure of my memories of these Church traditions.

Interestingly, Risley Presbyterian Chapel was founded by an Englishman! As mentioned, my mother didn’t appear to be that ‘religious’. To her, our family attending the Presbyterian church was a source of social ‘pride’ since it was particularly Scottish; this means this differentiates you from everyone else, especially the English. It therefore seemed somewhat incongruous (to me at the time) that Mr. Roberts was Welsh and not Scottish!

The Founder of the Risley Congregation

I can’t remember my mother actually saying anything explicitly about the inappropriateness of Roberts’ Welshness (not least his name), but it was inferred by her attitude. The Welsh, like the Irish, although having similar British/Celtic cultural roots as the Scots, were always treated with suspicion by my mother. She might have perhaps considered them to be even more ‘alien’ than the English. So although Risley Presbyterian Chapel, its congregations, nor its minister were ‘Scottish’, by some trick of the mind, we imagined it to be.

I have searched the Internet for information about the minister W. E. Roberts, but couldn’t find anything. In my mother’s records I found a booklet written by Roberts (1962) The Rev. Thomas Risley (this is included in an ‘external’ Appendix). That was a 16-page booklet about the founder of the Risley Congregation.

The article in the booklet is well-informed and well-researched and includes an impressive list of references at the back; in addition, it includes a list of the previous ministers; amongst these is J. J. Glover (the minister from 1905-1944); this was probably Miss Glover’s father. Miss Glover, as mentioned, was a member of the church and a friend of my mother’s.

Our Family’s Church Traditions

My mother was friends with one church people, an older woman called Miss Glover. She often visited my mother for tea in the afternoons when we were living at 26 Hob Hey Lane. She used to dress in navy blue suits and wore an old-fashioned bonnet. I remember her seeming a little stern to me as a young boy, but perhaps she was not used to children. I think her father was the minister of Risley church from 1905 to 1944.

Church services were pretty dreary without affectation and ceremony. It was more so for a child who views it as a sort of social happening my mother took part because there was nothing else better to do on a Sunday. Of course, attending church was still a great excuse to dress up the kids and make a ‘showing’ in the local community.

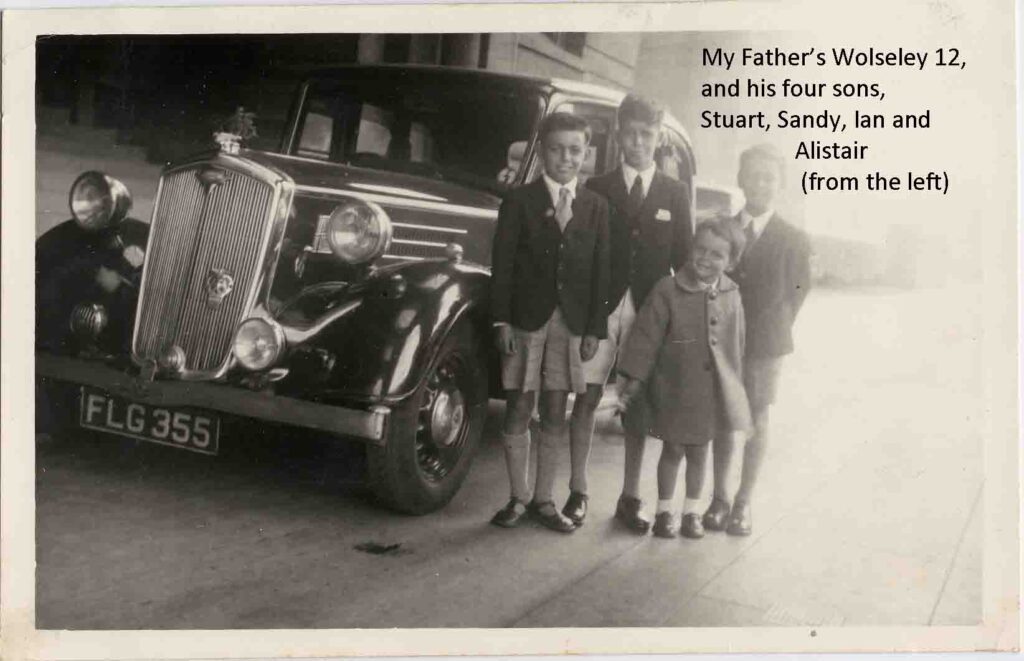

‘Dressed in your Sunday best’ is not a phrase that exists for no reason. In the 1950s and 1960s it had a literal meaning. The fact that the church was some distance from where we lived also meant that you had to arrive there by car; it became another appendage to your Sunday-best. I’ve included a photo of us four boys in our ‘Sunday best’ standing in front of our father’s ‘pride-and-joy’ – his Wolseley 12 (the photo is included in the section “Wolseley 12”).

Hymn Singing

The minister’s sermon usually consisted of a small ‘moral’ story and the congregation sang three hymns. These hymns were marked up on the wall on a wooden board. It had slots for numbers so that the hymn numbers could be changed every Sunday. I liked this arrangement, as it was about the only ‘interactive’ aspect of the church services. ‘Interactive’, in the sense that after sitting down on a church bench, you looked up at the board and found the appropriate number in your hymn book.

Numbers seemed to have more significance when you were young. I can still remember my two favourite hymns at Culcheth Primary School were numbered 129 and 131 in the school hymnbook. I think 129 was “Onward Christian Soldiers”.

Onward Christian Soldiers

Marching as to War

With the Cross of Jesus

Going on before.

We sang a hymn every day at school in the morning assembly of Culcheth Primary School. Of course, the words of hymns, prayers, and songs often have different meanings to children. As a child, you tend to only understand literal meanings and not metaphorical or analogous meanings. Thus, “marching as to war” sounded like some kind of glorious fun cutting off the heads of evil enemies while consoled by the fact that you were IN THE RIGHT.

Metaphors in Religion

Of course, when I was 11 years old, I hadn’t even heard of ‘infidels’ and ‘Muslims’. However, I was sure a quick search on the Internet will produce results – in relation to ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’; that is, the various ‘hate messages’ against other religions, such as Islam. In other words, it is not just children who have a literal understanding of religious texts; various Christian American presidents often send their soldiers off to kill Muslims (and other ‘infidels’) with the phrase, “God be with you!”

Addenda:

Of course, whether or not we interpret the word ‘soldiers’ metaphorically, or as referring to actual ‘soldiers’ of war, the Christian invasions of Islam countries in the previous decades obviously have their historical parallels in the Crusades. But we can’t delve into this here, although the reader might want to reflect upon how children in the West are socialized by the church and schools into the idea of inflicting violence on other peoples with different ideas.

Wooden Box Collection

Another aspect of ‘interaction’ at church on Sundays, or relief from boredom, was when the wooden collection box would be handed round; there were little brown envelopes that you put your collection money in, seal it, and deposit in the collection box; this was just a clumsy wooden contraption with a handle which somebody comes around with. I remember asking my mother why we had to put the money in a sealed envelope and then in a wooden box. She said it was fair that way. Everybody put something in the box no matter how small and no one knew how much you put in. Looking back, I suppose this was a Presbyterian democratic sort of thing.

The Church Communion

The holy communion was a highlight in any given Sunday service when it happened. It was an important ritual for the adults, but it annoyed me as a child. We weren’t allowed to drink the wine like the adults, but we were allowed to nibble the bread. If I remember correctly, it was a bit of an anti-climax anyway, because these were tasteless, small, dry weightless dice-cubes; and yet, the mere act of the ceremony seemed to promise more.

I remember asking my mother why we had to do this. She answered that the wine was the blood of Jesus, and the bread was his flesh. This sounded pretty disgusting to me, but I couldn’t really take this ‘cannibalism’ seriously, considering the absolute tastelessness of the bread.

It seemed to me, however, to be in tune with the rest of the Presbyterian Church – tasteless. I do remember though, that the services were mercifully short. A brief sermon, 3 hymns, and you were out again! Another advantage was that it was always the same, so you knew what to expect.

The Lord’s Prayer

The “Lord’s Prayer”, which all the school children would recite with their heads bowed every day before school dinner, was something you took literally:

“Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come; thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen”.

“Give us today our daily bread”. This didn’t make much sense either, as we didn’t get any ‘bread’, or at least it was not the main part of the meal. It would have been better to say, “Give us our daily mashed potatoes” or “Give us our daily custard.”

Also the word “give” made no sense to me, considering you bought your school dinner with your 2-shilling dinner-ticket and were not ‘given’ anything! I don’t think a single English school-child has ever understood the sentence: “and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.”

In other words, millions of English kids would recite this prayer every day without understanding what it meant. The kids were like the stupid sheep in Orwell’s novel, 1984, chanting “Four legs good, two legs bad.”

Trespassers will be shot (not forgiven)

As a child wandering around the English countryside, one would constantly be threatened by signs saying, “No Trespassing, Trespassers Will Be Prosecuted.” I found this sign on the Internet as a point of illustration. It is probably an American sign, as the Americans love shooting ‘innocents’. The English signs would just say, “No Trespassing. Trespassers Will Be Prosecuted!”

In other words, property owners in England were, by no means, going to “forgive anybody for trespassing!” Exactly how they intended to prosecute children was something we never got to understand. Saying that the English wouldn’t shoot you, unlike the Americans, is not wholly true either.

As children, we had plenty of stories of ‘mad cow’ farmers who were handy with their shotguns and would shoot fleeing kids in the bum when they were on their land. A search on the Internet will also show that it wasn’t just about extracting a few of the farmer’s shotgun pellets from your bum. It could also result in death, as in the case of the farmer Tony Martin who murdered a ‘trespasser’. Tony Martin was doing nothing more than keeping alive the good old English farmer’s tradition of ‘shooting trespassers’.

As kids, we didn’t really understand what the word “trespassing” in the warning, “No Trespassing, Trespassers Will Be Prosecuted” meant. But the sign was usually hung on a wall or fence surrounding property, so we understood that you weren’t allowed to climb over the wall or fence and there would be dire consequences if you did.

The meaning of the word ‘trespass’

Of course, later on you understand, as an adult, that “trespass” can mean “sin”. Without doing further research, it is perhaps not coincidental that “trespass” has two meanings in the English language: 1. to enter upon someone’s land unlawfully. 2: to do wrong: sin.

This seems to suggest that the uppermost wrongdoing in English societies is the violation of property and not the violation of people, which is, of course, contradictory to Christ’s teachings; however, this seems not contradictory to the capitalist ethic of Western societies.

To this day, people still value property over human life while claiming to follow religious teachings that say the exact opposite. The latest evidence of this, is the Russian slaughter of hundreds of thousands of innocents in order to ‘grab a bit of land’ (2022). That is, the devil rises again.

Religious Beliefs Growing Up

Attending church was part of some diffuse social class ritual when we lived in Culcheth, Lancashire. When we moved south to Billericay in Essex in the early 1960s, I don’t think we attended church on a single occasion, or later in the following years, apart from attending the various family weddings and funerals.

By the time I was old enough to comprehend some idea of religion at the age of eleven, I decided rather prosaically that what I couldn’t see didn’t exist. Later on, I decided that ‘not believing’ was in one sense ‘believing’, because to deny something exists is to contemplate that it might exist. What you end up with then is to accept that religions have some kind of social function; religious texts have various sources along with other texts. When I was around twenty or thirty years old, I read many of Bertrand Russell’s books.

Influence of Books

When I was attending Barstable Grammar and Technical School in Basildon, Essex in the 1960s, I was, on the whole, very bored. Sometimes we had so-called ‘free-periods’. We were then ‘allowed’ to go into the library. I remember one book that caught my attention was “The Best of O’Henry: Over 100 Stories.” These stories appealed to me because being a lazy boy, the stories could be read in a short space of time.

My ‘lazy’ mind was also attracted by the title, “In Praise of Idleness” – a collection of essays by the philosopher Bertrand Russell. Both these books appealed to me – being lazy while wanting to be an ‘intellectual’. This was thus the start of my exploration of Russell’s other books, of which there are many. Thus, eventually. I came across Bertrand Russell’s “Why I Am Not a Christian”.

My skeptical attitude towards various religions and political ideologies tends to be ‘instinctive’. But then, I am committing the same ‘crime’ as Christians and other religions and ideologies: the so-called ‘leap of faith’. In a way, the act of believing (or not believing) is being done outside the boundaries of reason. Thus, in this context, I thought i could least pay Russell the courtesy of reading his pamphlet.